The clinical manifestation of HIV-associated dementia carries a poor prognosis for the individual HIV-positive patient.

4,5,16 However, if detected early in the course of the disease, it may be amenable to antiretroviral therapy.

16–21 Effective screening for and adequate quantification of HIV-associated psychomotor slowing are therefore essential to patients, treating physicians, and researching scientists. The ideal screening tool should not be expensive; it should be universally available (ideally bedside), brief, sensitive and reliable in detecting “subcortical” dementia, and it should allow for the selection of patients for more extensive neuropsychological/electrophysiological testing and clinical trials. The HDS was explicitly designed to fulfill these criteria and has proved to be a beneficial screening tool.

2 Human immunodeficiency virus associated dementia is considered a subcortical dementia,

22–24 and its neuropathology focuses on the basal ganglia.

23–31 As the basal ganglia play a pivotal role in movement control,

32 the HDS emphasizes motor skills and timed tasks. Psychomotor speed is assessed with the timed, written alphabet and represents the most important subscore (6 out of 16 points). The construction task (cube copy time) is also a timed task and scores the time needed to correctly copy the cube (another 2 points). Timed motor tasks thus account for 50% of the HDS sum score. With this design, the HDS actually screens for psychomotor slowing. Accordingly, we observed highly significant differences between patients scoring >10 and ≤10 in the HDS for both contraction time and MRAM (

Table 2). These parameters have been shown to sensitively describe psychomotor slowing in HIV-positive clinically yet unaffected patients.

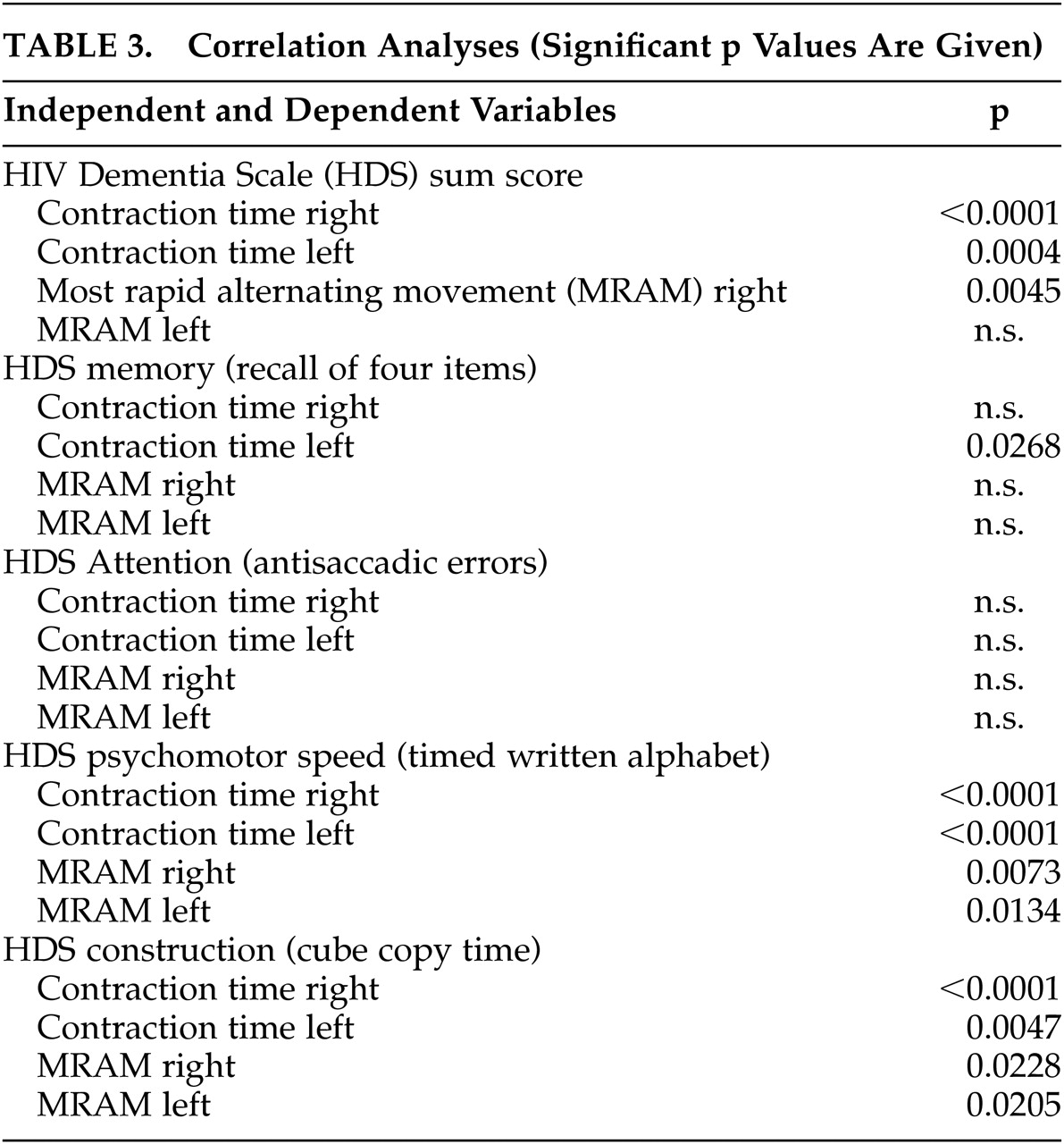

8 Analysis revealed significant correlations between contraction time and MRAM on one hand and HDS sum score and HDS subscores for psychomotor speed and construction on the other hand (both timed tasks) (

Table 3). Memory and attention do not correlate with contraction time or MRAM. In our population, HDS defines approximately 20% of patients as mildly demented or at risk for HIV dementia. This percentage is comparable to the percentage that we observed in a long-term survey,

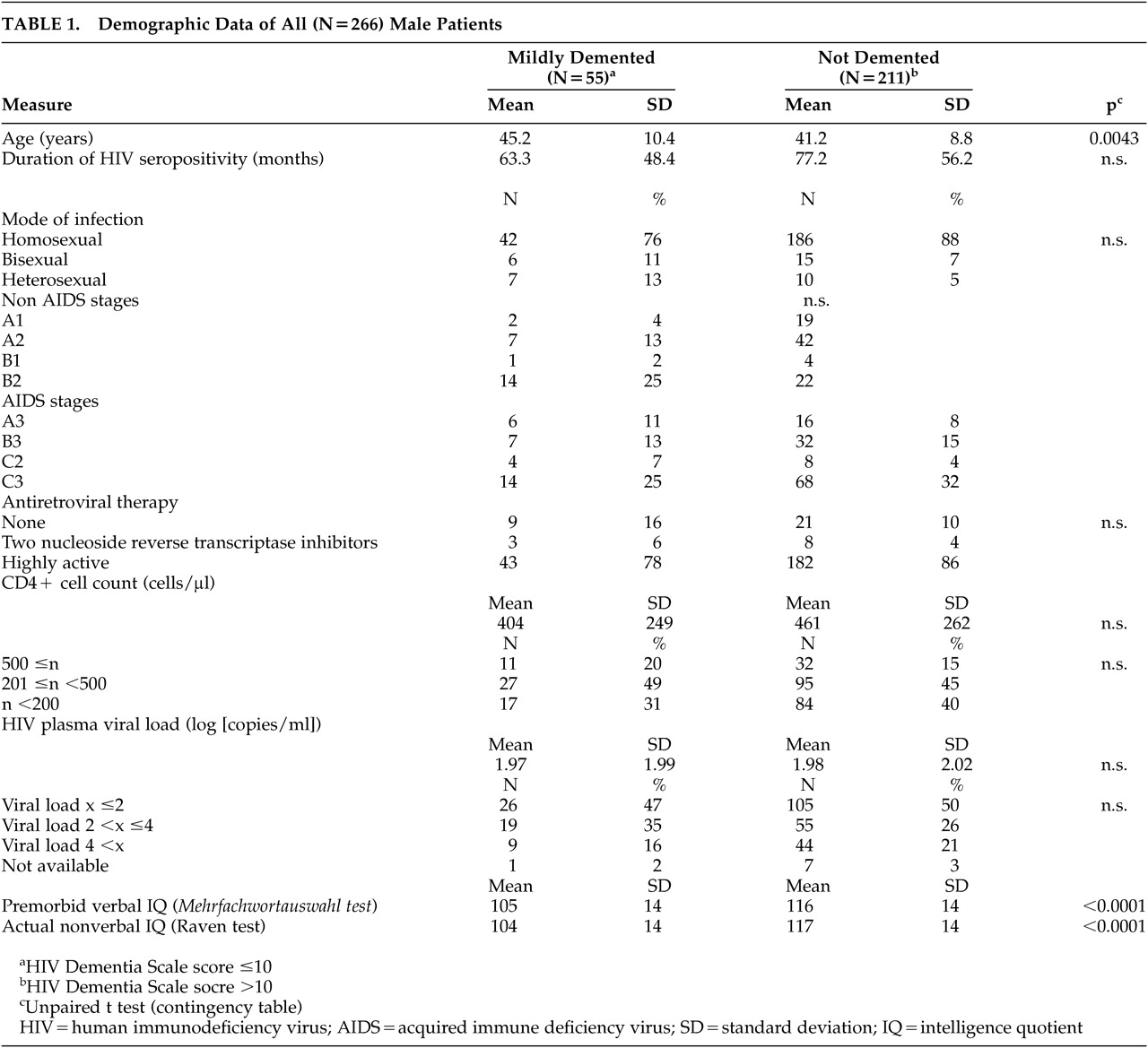

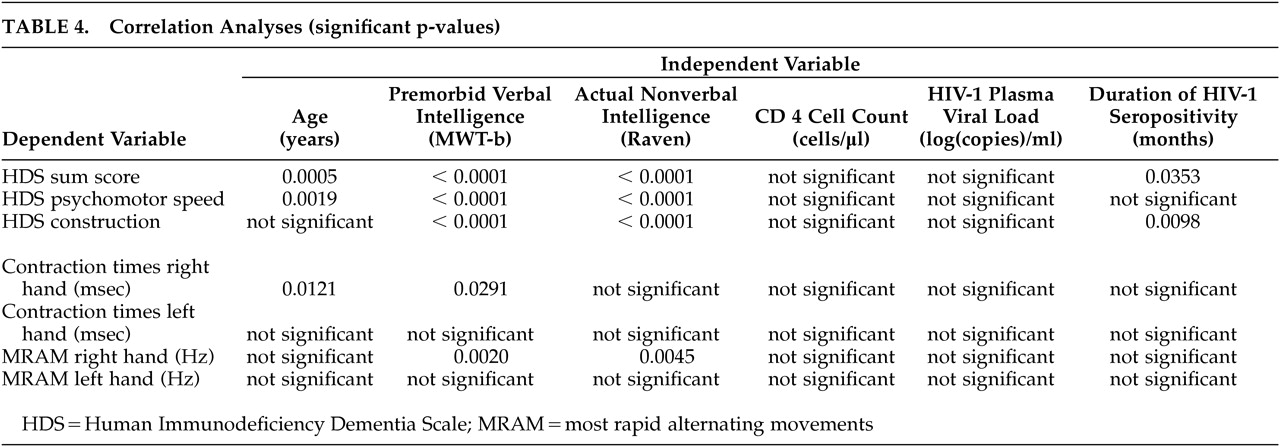

20 where the prevalence of pathological contraction time ranged between 12% and 16% for the years since introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1996. In the original study population, the HDS score was relatively independent of age and education. In our patients, we found significant differences between patient groups for age, premorbid verbal intelligence quotient (IQ), and actual nonverbal IQ. We also observed significant correlations between the HDS sum score and the subscores for psychomotor speed and construction and for the premorbid verbal and actual nonverbal IQ (Table 4), which were less marked for age and duration of HIV-seropositivity. These correlations reflect the influence of intelligence on a dementia scale. This is obvious for the premorbid verbal intelligence and a subtest evaluating the written alphabet, as it is for the actual nonverbal intelligence and a dementia scale. In the original HDS, the authors stated accordingly, “The HDS may be insensitive to mild HIV dementia in highly educated patients.” Thus, a possible interference has not been excluded. In our cohort, electrophysiological motor testing, as quantified by MRAM and contraction time, was almost completely independent of both premorbid and actual intelligence. This finding is in contrast to other studies

33 and probably reflects that this test battery focuses on motor performance. In this study, we show that electrophysiological motor testing is not influenced by premorbid or actual intelligence, and, in earlier studies, we have demonstrated that it is not influenced by intravenous drug use,

34 concomitant depression,

35 or peripheral nerve damage.

36 Compared to the HDS, this test battery is a simple continuous measure that cannot serve as a simple screening tool for reasons of equipment. However, as a more quantitative method, it is useful in monitoring the course of dementia as well as deterioration and response to antiretroviral therapy.

15,17,21 Furthermore, as it is less subject to potentially interfering factors (see above), electrophysiological motor testing is useful in studies on HIV neuropathogenesis, with a special focus on basal ganglia dysfunction

30,31 In fact, electrophysiological motor testing cannot and should not replace a complete neuropsychological assessment that necessarily covers skills in a variety of domains that are involved in HIV dementia. In conclusion, we view the domain of neuropsychological testing in the description of all deficits observed, the domain of the HDS in rapid screening for psychomotor slowing, and the domain of electrophysiological motor testing as a scientific tool to quantify one pivotal deficit in HIV neuropathogenesis: basal ganglia mediated psychomotor slowing.