Many studies have shown that older patients with depression have impaired cognition across a wide range of domains, including executive function.

1–3 An intact executive system is required for tasks that involve working memory, the ability to retrieve and process information.

4 The digit span forward (DSF) and digit span backward (DSB) tests have been used in depressed patients to assess working memory. While DSB does involve additional cognitive processes compared with DSF, the extent of involvement of the central executive system is unclear.

As the executive system is thought to be accessed during manipulation of information, a natural neuropsychological test to emerge is the Ascending Digits Task (ADT), in which subjects are asked to reorder a sequence of numbers in ascending order. This type of mental activity is thought to be carried out by the central executive system of working memory. Because neither DSF nor DSB require manipulation of information to a great degree, while the ADT does, the latter task may be better to assess executive function.

To our knowledge, this task has not been reported previously to assess dysfunction of the central executive system in depressed patients. The purpose of the present study was to examine working memory and executive dysfunction in older depressed patients using the ADT. We hypothesized that older depressed patients would perform more poorly on the ADT when matched against a nondepressed elderly comparison group.

METHOD

The Sample

Participants consisted of 129 depressed and 129 nondepressed individuals enrolled in National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-sponsored Clinical Mental Health Clinical Research Center (MHCRC) at Duke University Medical Center. Depressed individuals met DSM–IV criteria for major depression, and all participants were at least 60 years of age at baseline enrollment. Exclusion criteria for the MHCRC study include the following: another major psychiatric illness including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder; alcohol or drug abuse or dependence; clinically diagnosed primary neurological illness, including dementia; unstable medical illness or physical disability that affect cognitive function. After complete description of the study to the participants, written informed consent was obtained.

Assessment Procedures

At baseline, a trained interviewer administered the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule

5 to establish a diagnosis of major depression in depressed individuals, and to rule out current and past depression in comparison subjects. Depressed subjects received standardized clinical assessments, including the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),

6 a depression scale that is well suited to assessing the elderly, with its focus on somatic symptoms often seen in this population. A trained psychometrician administered the ADT to all participants as part of a larger battery that also included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

7Ascending Digits Task

In this task, the examiner reads a series of numbers and asks the subject to reorder the numbers in ascending order, from smallest to largest. In this study, participants were read lists ranging from two to eight numbers and were allowed a maximum of two tries at each level. The task was stopped if the subject made two errors at a given level or completed eight digits correctly.

Statistical Analysis

Because the two groups were not matched up front, we tested bivariate differences between the two groups on key demographic and cognitive covariates—age, education, and MMSE score—using Student’s t test for continuous measures, and chi-square analyses for important categorical variables—gender and race. The bivariate difference in the ascending digits score between groups was tested using Student’s t test.

For multivariate models, the ascending digits score was regressed on a proxy variable denoting group membership controlling for demographic covariates and MMSE score. Given the approximate normal distribution of ADT scores, we used ordinary least squares regression procedures. In addition to the main effects model, a series of interaction models were estimated, each including an interaction term between the group proxy and one of the four demographic covariates. To assess for association between depression severity and cognitive function, a last model was estimated substituting MADRS score at time of testing for the diagnostic proxy with the sample restricted to the depressed cohort.

RESULTS

The sample included 258 subjects, equally divided between the nondepressed comparison (N=129) and depressed (N=129) cohorts. When matched against depressives, comparison subjects were comprised of a higher percentage of women (73% versus 59%; χ2=6.26, p=0.012), were older (76.2 versus 73.4 years; t= [256], df=[3.25], p=[0.0013]), and reported more years of education (15.8 versus 14.2; t=[256], df=[4.28], p=[<0.0001]). Both groups were largely Caucasian (84% versus 90%; χ2=2.17, p=0.14). Comparison subjects scored higher on the MMSE than patients (28.72 versus 27.51; t=[205], df=[4.63], p=[<0.0001]). On the ADT, comparison subjects scored 1.75 units higher than patients (9.52 versus 7.75; t=[245], df=[5.74], p=[<0.0001]). On average, depressed participants had an average MADRS score of 22.33 (SD=7.77), a lifetime total of 5.6 (SD=10.3) depressive episodes, and were 25.2 (SD=29.1) months into the current episode.

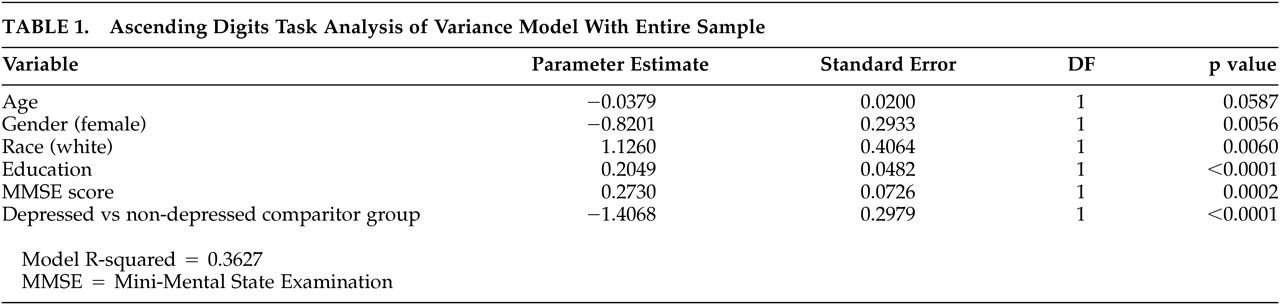

In a multivariate regression analysis controlling for age, sex, race, education and MMSE score, depressed subjects scored significantly lower on the ADT relative to comparison subjects (

Table 1).

In a separate regression analysis restricted to the depressed cohort, the MADRS score was not significantly associated with patient performance on the ADT (p=0.58).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that older depressed patients perform worse on the ADT compared with elderly comparison subjects. We also found that although a diagnosis of depression was associated with a significantly lower ascending digits score, the latter was apparently not influenced by depression severity when we examined the depressed group separately.

The ADT involves manipulation of information that is thought to be carried out by the central executive system of working memory. In Baddeley’s model of working memory, the central executive system controls attentional resources to two slave systems, the phonological loop, concerned with speech-based information, and the visuospatial sketchpad, which is involved with visual images.

4 DSF is thought to involve the phonological loop, while DSB is thought to involve the central executive to some degree.

8,9 Because these more commonly used digit span tests do not involve a more complex manipulation of information, the ADT may be better to assess executive function.

There are several potential limitations that need to be addressed. First, it is possible that worse performance on the ADT is due to impairment in attention or motivation. When cognitive demands pass a threshold, depressed individuals may shut off their attentional or motivational mechanisms earlier than comparison subjects. While we did not examine attention or motivation in this study, previous studies have demonstrated that performance on the DSF task is no different between depressed individuals and comparison subjects, thus indicating that attention or motivation is not impaired in depression during this task.

8,10,11In addition, depression encompasses a variety of symptoms. It is possible that performance on the ADT is impaired in depressed individuals with a certain subset of depressive symptoms, for example those that complain of diminished ability to concentrate. In a post-hoc analysis, we examined the relationship of the MADRS concentration item and ADT score and found no significant association (Pearson r= −0.042, p=0.60). We have also shown that performance on the ADT was not dependent upon the severity of depression as measured by MADRS scores. This is consistent with previous findings that performance on two working memory tasks carried out simultaneously was not related to severity of depression but to the presence of depression.

12Additionally, we did not examine the total length of time in which a subject was depressed, nor did we examine the number of recurrences each patient had. There is some evidence that subjects who have recurrent depression perform worse on memory tests than those in depression for the first time.

13 This, and the length of time a person has been depressed, may contribute to cognitive dysfunction through anatomical changes that accumulate. For example, the hippocampus

14 and the amygdala

15 have been shown to be reduced in size in depressed individuals matched against comparison subjects.

Executive dysfunction in older depressives may be due to degenerative, anatomical frontal lobe changes. Alternatively, the anatomical integrity associated with normal executive function may be maintained, but frontal lobe systems may be either unable to be activated or are inhibited through an unknown mechanism. While the pathophysiology of frontal lobe dysfunction is not known, it may have features of both a degenerative process and a disconnection syndrome. For example, remission from depression has not been shown to improve performance in certain memory tasks.

12 On the other hand, a “Depression–Executive Dysfunction Syndrome” has been described that supports the notion of frontal pathway disruption.

3In conclusion, our study demonstrates that depressed individuals perform worse on the ADT matched against comparison subjects. We speculate that this difference may be due to a deficit in central executive function, as the task involves manipulation of information held in working memory. As studies have demonstrated frontal lobe dysfunction in depressed individuals that correlate with deficits in executive functioning, the ADT may be a useful tool to explore frontal dysfunction in depressed patients. Functional neuroimaging studies using this task may shed further light into the exact nature of executive dysfunction associated with depression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIMH grants P50 MH-60451, R01 MH-54846, and K24 MH-70027.