Increased incidence of personality disorder is common in head-injured samples,

6 provided that one ignores DSM-IV criteria that the pattern of behavior not be due to the effects of a general medical condition (e.g., traumatic brain injury). Personality disorder diagnoses have been made in 23% of TBI patients at 30-year follow-up, with avoidant, paranoid, and schizoid as the most common diagnoses.

7 Although a distinct neuropsychological profile for the personality disorders has yet to emerge, the bulk of the evidence supports a neurobehavioral basis for borderline, schizotypal, and antisocial personality pathology.

8 –

11 Despite findings revealing a decrement in frontal lobe function associated with several forms of personality disorder symptomatology,

12 little is known about the relations between other domains of neuropsychological functioning and personality pathology in patients who sustain TBI.

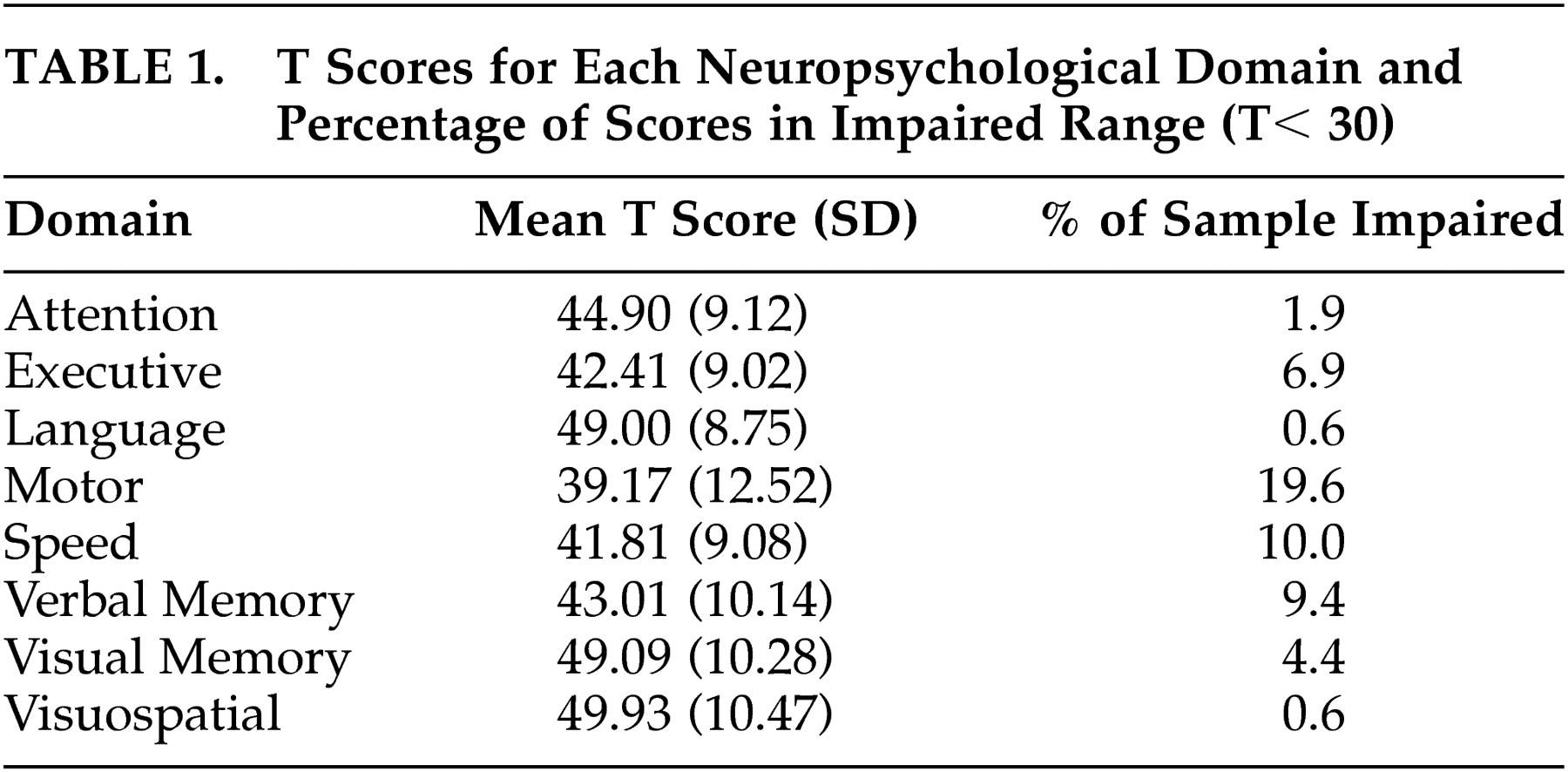

RESULTS

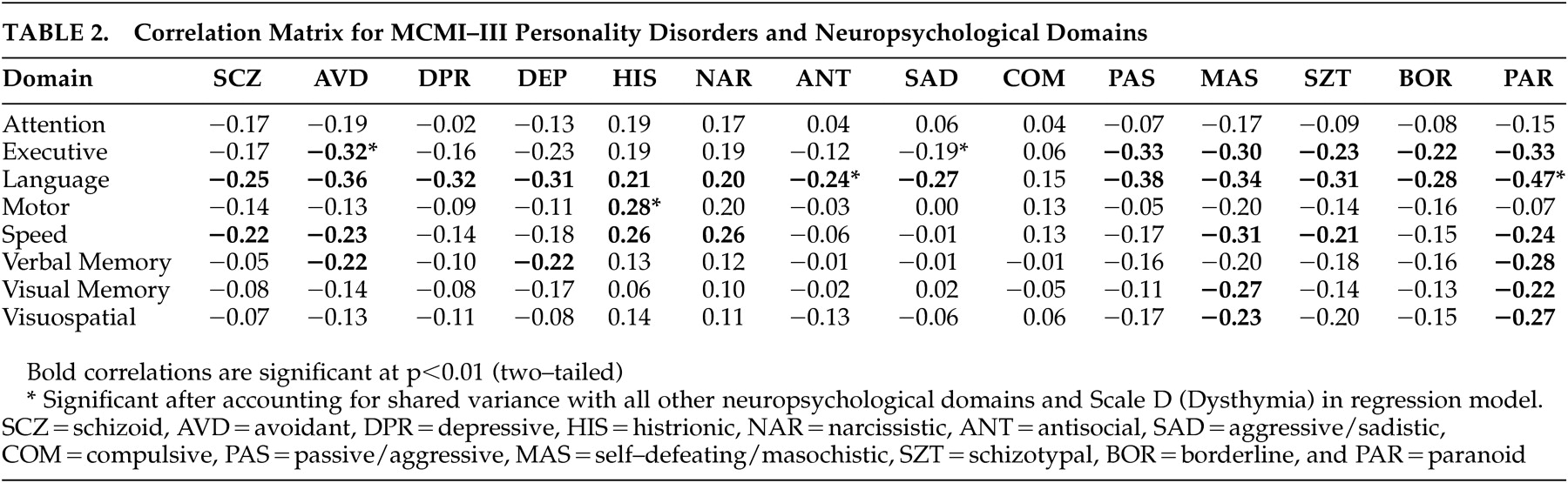

Table 2 shows the correlation matrix for the MCMI–III personality disorder scales and neuropsychological domains. Linear regression analyses were conducted for each of the personality disorder scales with the eight neuropsychological domains as predictors. A significant association was observed between language and schizoid symptomatology (β=−0.323, t [8, 143]=−3.37, p=0.001), while executive function (β=−0.224, t [8, 143]=−2.20, p=0.029) and language (β=−0.350, t [8, 143]=−3.83, p<0.001) were significant predictors of avoidant (AVD) symptomatology. For dependent (DEP), depressive (DPR), antisocial (ANT), obsessive-compulsive (COM), and self-defeating/masochistic (MAS) scales, language was the sole predictor of these traits [DEP β=−0.304, t (8, 143)= −3.20, p=0.002; DPR β=−0.382, t (8, 143)= −4.03, p<0.001; ANT β=−0.212, t (8, 143)=−2.06, p=0.04; COM β=0.219, t (8, 143)=0.212, p=0.04; MAS β=−0.273, t (8, 143)=−2.94, p=0.004]. Motor skills [β=0.205, t (8, 143)=2.29, p=0.02] and language [β=0.217, t (8, 143)=2.31, p=0.02] were significant predictors of scores on the histrionic scale, whereas processing speed [β=0.244, t (8, 143)=2.13, p=0.04] was the only neuropsychological domain associated with narcissism in the regression model. Both executive function [β=−0.274, t (8, 143)=−2.61, p=0.01] and language [β=−0.274, t (8, 143)=−2.61, p=0.01] were significant predictors of aggressive/sadistic traits. For passive-aggressive traits, attention [β=0.214, t (8, 143)= 2.14, p=0.03], executive function [β=−0.316, t (8, 143)=−3.15, p=0.002], and language [β=−0.358, t (8, 143)= −4.00, p<0.001] were significantly associated with this scale.

Linear regression analyses were also conducted on what Millon conceived as the severe personality pathologies, schizotypal (SZT), borderline (BOR), and paranoid (PAR). Language significantly predicted scores on each of these personality scales [SZT β=−0.291, t (8, 143)=−3.08, p=0.002; BOR β=−0.265, t (8, 143)=−2.76, p=0.006; PAR β=−0.404, t (8, 143)=−4.56, p<0.001].

When Scale D (dysthymia) was included in the regression model, a number of associations between neuropsychological domains and personality disorder traits were rendered nonsignificant. With the exception of the antisocial scale, the significant effect of language was removed for each of the following scales when Scale D was included in the regression model: schizoid, dependent, depressive, antisocial, obsessive-compulsive, self-defeating/masochistic, schizotypal, and borderline. Similarly, processing speed no longer predicted narcissistic traits when Scale D was included in the regression model. A number of neuropsychological domains remained significantly associated with personality disorder traits even after accounting for shared variance with other neuropsychological domains and Scale D (

Table 2 ). Executive function remained a significant predictor of avoidant and passive-aggressive traits when Scale D was included in the regression model, as did motor skills for the histrionic scale and language for aggressive/sadistic and paranoid scales.

We conducted a canonical correlation analysis using the eight neuropsychological domains as predictors of the 14 personality scales to evaluate the multivariate shared relationship between the two sets of variables. The analysis generated seven functions with squared canonical correlations of 0.255, 0.177, 0.122, 0.096, 0.070, 0.045, and 0.013 for each successive function. Using Wilks’ λ=0.427, F (98, 837.44)=1.23, p=0.07, the full model across all functions was not statistically significant. It should be noted that the canonical correlation is underpowered, necessitating an n to k ratio of 20:1, which is not satisfied by the sample size of the present study. However, given that Wilks’ lambda represents the variance unexplained by the model, 1 – λ represents an r 2 metric of the full model’s effect size. Thus, the r 2 type effect size was 0.573 for the set of seven canonical functions, which indicates that the full model explained approximately 57% of the variance shared between the variable sets.

Because personality disorders are unevenly distributed across gender,

25 separate post hoc correlation analyses were conducted for men and women in order to examine the role of gender as a potential moderating variable. Many of the correlations for both men and women were attenuated when examining individual correlations by gender. Although a handful of correlations were no longer statistically significant (p<0.01) relative to whole-group analyses, the most prominent findings were in the domain of language: for women, only passive-aggressive, self-defeating/masochistic, schizotypal, and paranoid traits were associated with language skills, while nearly all of the associations between language and personality disorder traits were maintained for men, with the exception of antisocial and aggressive/sadistic traits. Similarly, for speeded processing, only self-defeating/masochistic traits were associated with this neuropsychological domain for women, whereas for men the schizoid, avoidant, self-defeating/masochistic, and schizotypal traits remained statistically significant. Furthermore, while verbal memory was uncorrelated with personality disorder traits for women, men maintained a significant association with paranoid traits in addition to narcissistic, passive-aggressive, and schizotypal traits.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with findings in a healthy adult sample,

12 neuropsychological functioning was associated with many personality disorder traits rather than isolated personality disorder symptomatologies. Gender differences in these associations were apparent in a number of domains, particularly language skills, speeded processing, and verbal memory. The most robust correlations were observed for men, suggesting that there may be key ways in which men and women differ in certain personality traits and that these differences may be associated with unique neurocognitive underpinnings. Generally, however, associations present in the entire sample tended to be maintained, albeit at a smaller magnitude, when gender was examined as a moderating variable. The personality disorder scales that had the broadest set of correlations with the neuropsychological domains were avoidant, dependent, self-defeating/masochistic, schizotypal, and paranoid, all of which were correlated with at least three of the eight domains. Of these personality pathologies, schizotypal personality disorders solely have received extensive neuropsychological examination in the literature.

For those personality disorders generally considered within the schizophrenia spectrum, deficits were apparent within specific neuropsychological domains even after accounting for shared variance with depressive symptomatology. While avoidant traits were associated with reduced executive function and paranoid traits with language deficits, no neurocognitive functions were associated with schizoid symptomatology after accounting for depressive symptoms. Further evaluation of executive function deficits in patients with avoidant traits may be warranted given the absence of any data implicating executive dysfunction in association with avoidant symptomatology in the literature.

We observed a dissociation in language and executive function for the two scales indicative of psychopathic attitudes and behavior. The antisocial scale, which emphasizes social mistrust, behavioral acting-out, and social independence,

23,

26 was associated with language deficits, whereas the aggressive/sadistic scale, which focuses more on emotional acting-out, strong-willed determination, and defensive aggression,

23,

26 was linked more strongly to deficiencies in executive function. These data are consistent with findings of weak associations between antisocial personality traits and executive function but robust links between psychopathic behavior and executive dysfunction.

11 Thus, overt hostile and aggressive behavior, as represented more by the aggressive/sadistic scale, may be more indicative of organic frontal lobe impairments (e.g., disinhibition), while an antisocial personality and associated attitudes, as indicated more by the antisocial scale, may be linked more strongly to deficits in language skills.

The present investigation provides evidence of a unique set of relations between neuropsychological functioning and passive-aggressive (or negativistic personality disorder) symptomatology, a disorder listed in DSM-IV for further study. Though executive function and language were associated with passive-aggressive traits, when depressive symptomatology was accounted for in the regression model, executive function remained the sole neuropsychological domain significantly associated with passive-aggressive traits. The passive-aggressive scale had the largest standardized regression weight associated with executive function deficits and was one of the few personality disorder traits—along with avoidant and aggressive/sadistic—linked to executive dysfunction after accounting for depressive symptomatology and shared variance with other neuropsychological domains. These findings suggest that passive-aggressive traits may be a more severe form of personality pathology with substantial deficits in higher-order regulatory and supervisory functions subserved primarily by the frontal lobes.

27 Of course, this assertion ought to be confirmed with a cohort of diagnosed passive-aggressive patients with no history of neurological insult.

Histrionic and narcissistic traits seem to be associated with enhanced functioning in a number of neurocognitive domains, which is consistent with the finding that higher scores on the hysteria scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2 (MMPI–2) are associated with greater intellectual ability.

28 With the level of depression accounted for, motor skills were significantly associated with scores on the histrionic scale. Similarly, narcissism scores were related to higher levels of speeded processing, but this association was eliminated when depressive symptomatology was included in the regression model. Poor performance on measures of motor skills and processing speed are reflective of frontal deficits and more diffuse cerebral impairments. The associations between these neuropsychological domains and histrionic and narcissistic scores are positive, suggesting that these personality traits are associated with more intact frontal and generalized cerebral function.

Though normal variation in these traits may be neurocognitively advantageous, more extreme expressions of these traits may be neuropsychologically detrimental. Examining potential moderating factors that might affect these findings is also warranted. For instance, differentiating between the more maladaptive “vulnerable” versus the more adaptive “grandiose” narcissist

29 in neuropsychological domains might be revealing.

Executive function, speeded processing, and language skills were the primary neuropsychological domains implicated in personality disorder traits. Executive function and speeded processing are skills primarily subserved by the frontal lobes, suggesting that many forms of personality disorder symptomatology might at least partly be represented by pathological behavioral manifestations of frontal lobe dysfunction within this head-injured sample. Language skills, as presently defined, consist of expressive word knowledge, abstract reasoning, naming, commonsense reasoning, and social judgment. These also rely heavily upon anterior rather than posterior brain regions. On the whole, these findings implicate a more diffuse and generalized disturbance of personality which may be mediated by the disruption of frontal-subcortical circuits that govern the appropriate inhibition and expression of behavior and emotion, which collectively might be referred to as a disordered personality.

A consistent finding across several of the personality disorder scales was that many of the associations between personality traits and neuropsychological domains were rendered nonsignificant when shared variance with depressive symptomatology was taken into account. We conducted post hoc analyses to determine whether years of education might mitigate the relationship between language and depression. Education level, however, did not attenuate the association between language skills and depressive symptomatology.

Another postulation is that the relation between language task performance and elevations on the personality disorder scales might be mediated by depressive symptomatology, wherein greater levels of negative affect might impede performance on cognitive tasks as a result of depressed mood while also predisposing one to report more symptoms of disordered personality. However, language functions are generally preserved for depressed persons,

30 arguing against a specific decrement in performance on language tasks resulting from low mood.

It also may be possible that compromised temporal regions of the brain bring about greater levels of depressive and personality disorder symptomatology in tandem with poor performance on tests of language. Indeed, comorbidity of depression and personality disorders is pervasive,

31 left compared with right temporal lobectomy is associated with greater levels of negative affect,

32 and depression is more common in left- versus right-sided stroke.

33 Furthermore, one of the primary circuits postulated to be involved in secondary depression is a basotemporal-limbic pathway that links the orbitofrontal cortex and anterior temporal cortex through the uncinate fasciculus.

30 If this is the case, then the findings observed in this investigation suggest that dysfunction of temporal regions of the brain might bring about pronounced depressive symptomatology but only moderate levels of personality pathology, with the former overshadowing the latter. Findings in accordance with these results were obtained in a sample of healthy adults in which levels of negative affect apparently overshadowed the associations between frontal lobe-mediated tasks and several MMPI–2 personality disorder scales.

12 Support for temporal lobe dysfunction in personality disorders is also provided by functional neuroimaging examinations of borderline personality disorder in which abnormalities of temporal regions have been observed in positron emission tomography studies.

34,

35The multivariate shared relationship between personality disorder symptomatology and neuropsychological domains is considerable. Though the canonical correlation between the two sets of variables was not statistically significant, 57% of the variance was shared across these variable sets. Interestingly, attachment style has been shown to share approximately 56% of the variance in MCMI–III personality scales.

24 Evidently, brain function is as pertinent as some of the more venerable and extensively studied psychodynamic variables to the study of personality pathology.

The present study highlights the need to develop a comprehensive understanding of the neuropsychological and neuroanatomical underpinnings of the personality disorders and personality disorder traits, as has already been initiated with borderline,

8,

9 schizotypal,

10 and antisocial personality disorders.

11 Particular emphasis might be placed on avoidant, aggressive/sadistic, and passive-aggressive personality disorders, traits of which were shown to be associated with demonstrable deficits in executive function, the latter two of which are not currently listed on Axis II of DSM-IV. A neurobehavioral basis for these and nearly all of the personality disorders seems tenable, likely because the processes governing normal and disordered expressions of personality are themselves dimensional and mediated by dynamic neural systems that function along continua. Indeed, a neurobehavioral basis for the personality disorders calls into question the distinction of personality disorders from Axis I conditions based solely on an argument of biological etiology.

36Because the patients in this study were not necessarily personality disordered but instead had sustained a mild closed head injury, the implications of these findings for psychiatric patients should be interpreted with caution. There may or may not be deficits in neuropsychological functioning unique to individuals who are diagnosed with a personality disorder, particularly if there is no history of brain compromise.

However, these findings indeed shed light on potential neurocognitive deficits that may be involved in specific personality disorders that have not received extensive evaluation in the neuropsychological literature. Knowledge of those cognitive dysfunctions that might be pervasive among the personality disorders or strongly associated with specific traits would be crucial to consider when formulating treatments for personality disorder patients, particularly for psychopharmacological agents with known impact on specific cognitive functions.

In addition, the statistical analyses implemented in the present study assume a linear relationship between personality traits and neurocognitive functioning when, in fact, a nonlinear relationship may predominate. It may be the case that extreme levels of a particular trait in association with a diagnosable personality disorder may be reflected in neurocognitive dysfunction, whereas moderate levels of some traits may be associated with enhanced neurocognitive function. In investigations with suitably large sample sizes it will be necessary to use nonlinear approaches to further explore these relationships. In addition, it should be noted that the findings of the present investigation are indeed tentative given that most of the correlations between personality disorder scales and neuropsychological domains do not meet statistical significance after a Bonferroni correction.

To investigate the potentially causal role of brain injury on personality disorders, prospective research designs would be advantageous not only to determine which personality disorders occur most frequently following TBI but also to examine the influence of TBI severity and localization of insult on personality pathology. Compared with epidemiological studies that have investigated personality functioning among persons reporting a history of TBI,

3 prospective longitudinal designs would allow for a determination of whether differences in personality profiles among head-injured and non-head-injured persons are due to the presence of certain personality traits that tend to predispose one to TBI or whether neurological insult itself causes personality disorders. It may also be the case that certain predisposing personality traits act as risk factors for engaging in high-risk activities, and should a TBI occur, those and likely most personality traits may become more extreme and inflexible, crossing the boundary from personality style to disorder.

Findings from the present investigation and a healthy adult sample

12 implicate more global associations between personality disorder traits and neuropsychological functioning, suggesting that each of these psychological domains exists along a continuum wherein disruptions in brain functioning would likely result in an exacerbation of both premorbid personality traits and neuropsychological functioning. Evidence from a large sample of TBI patients certainly indicates that shifts toward more extreme expressions of normal personality traits occur following TBI.

37Combined approaches integrating personality, neuropsychological, and functional neuroimaging methods are important for characterizing the neural bases of normal and disordered personality. Though neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies have provided a wealth of evidence implicating multiple brain regions and neural systems involved in several forms of personality pathology, the results generally possess limited clinical utility.

9 One means by which to overcome the weak clinical utility of these findings is to enhance the ecological validity of neurocognitive investigations of personality disorders. Neuroimaging techniques, particularly those that employ ecologically valid interpersonal paradigms, as are afforded by such emerging technologies as functional near infrared spectroscopy,

38 and in the context of a multitrait-multimethod framework,

39 will likely provide useful insights into the neurodynamics of the personality disorders.