A pathy is a complex neurobehavioral syndrome associated with poor treatment compliance and outcome, caregiver distress, and decreased level of function across a number of health conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, traumatic brain injury, and HIV/AIDS.

1 –

8 Despite this pervasiveness, Marin et al.

1,

2,

9,

10 found a lack of appropriate assessment tools developed specifically for apathy. This led to the development of the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) to characterize and quantify apathy in individuals ages 55 and older.

1,

2,

9,

10 The scale has three versions: self-rated (AES-S), informant-rated (AES-I), and clinician-administered (AES-C).

2 Marin et al.

2,

10 reported that all versions of the AES differentiated between dementia groups according to levels of apathy.

2,

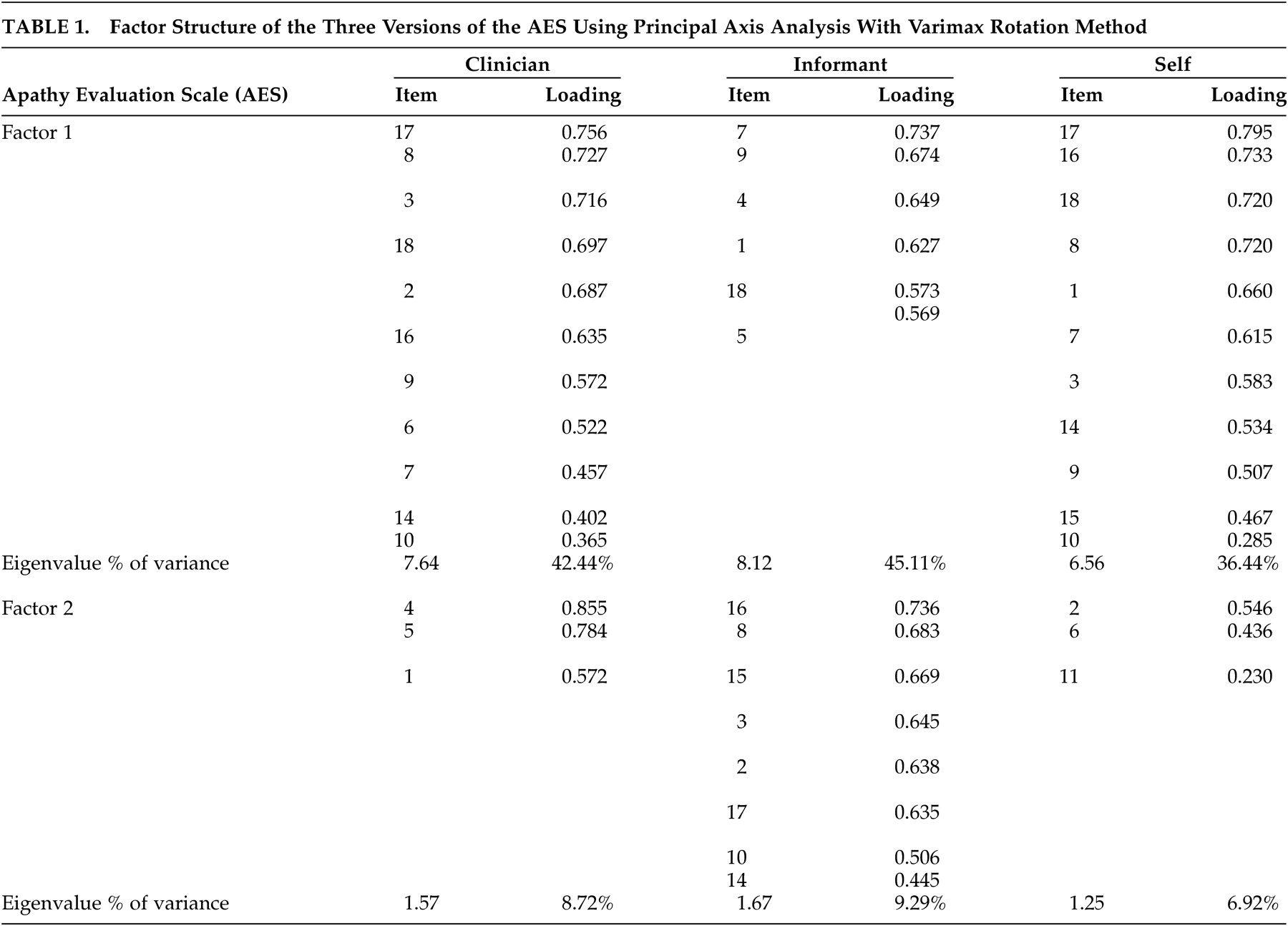

10 For the most part, the scale was found to be a single factor scale with apathy accounting for 32% to 53% of the variance.

2 Interest (5% to 10% of the variance) and insight/concern (7% to 8% of the variance) factors were also identified.

2 Together, the three factors accounted for 50% to 65% of the total variance.

2 The scale reportedly has good interrater (Cronbach's alpha (α)= 0.86–0.94) and test-retest reliability (α= 0.76–0.94). Marin et al.

2,

10 reported a cutoff score of 37.5 for the AES-C, which was two standard deviations above the score for normal healthy elderly persons, but the sensitivity and specificity were not indicated.

Other studies have provided support for the scale’s ability to differentiate between apathetic and nonapathetic individuals

2,

5,

10,

11 and between dementia groups

2,

5,

6,

10 with the AES-C. However, there is a lack of studies that reassess the factor structure and psychometric properties of the scale. Our recent critical appraisal of the psychometric properties of the AES-C (submitted) called for a more analytical assessment of the measurement properties of the scale. We suggested that with sufficient sample size, the properties of the scale should be reassessed in diagnostic and age groups that are different from those who were originally tested.

This article reexamines the factor structure of the three versions of the AES and identifies cutoff scores for apathy. The study also examines the psychometric properties of the three versions of the AES, including sensitivity and specificity, using the identified cutoff scores, and reliability and validity. It is hoped that information from this study will inform future use of the scale in the assessment of apathy in dementia and ultimately enhance treatment regime.

METHOD

Participants were drawn from the Behavioral Neurology Clinic at Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care in Toronto, Canada. This is an outpatient multidisciplinary clinic headed by Behavioral Neurology. The team comprised clinicians in neurology, psychiatry, neuropsychology, communication disorders, occupational therapy, and social work. The clinic provides thorough diagnostic assessments and management to patients with cognitive disorders. The referral sources were primary care physicians and specialists.

The study sample represents individuals in whom the presence of dementia was strongly suspected and who were referred to psychiatry (RvR) for assessment and/or management between January 1997 and December 1998. This represented 121 of the 170 participants seen by the behavioral neurologist (MF) during the 2-year period. The sample consisted of community-dwelling individuals still living in their own homes and a few nursing home residents (4.2%). All were able to attend outpatient assessments.

The Psychiatric Assessment

The psychiatric assessments consisted of two components: first, participants and their caregivers were seen by the clinical research assistants who administered a battery of tests to assess for presence of apathy and other neurobehavioral conditions, such as depression, psychosis, and agitation. Participant and caregiver/relative interviews were conducted separately by different clinical research assistants who collected information on age, sex, marital status, level of education, and living situation. A summary of the results was compiled and presented to the psychiatrist (RvR) and his resident, who incorporated this information (as is appropriate for this clinical data) into the psychiatric assessment.

Next, the psychiatrist and his resident then completed their own (but unblinded) clinical assessment for apathy, depression, psychosis, and other behavioral changes. The psychiatrist's diagnostic conclusions for apathy, which were based on criteria proposed by Marin,

1,

9 were taken from the consultation note and used as the gold standard in the study. The psychiatrist (RvR) is a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons in Canada (equivalent to board certification in the United States) and has worked extensively with this patient population in his clinical practice.

Apathy, in the month prior to the interview, was measured using the three versions of the AES. The apathy subscale of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)

12,

13 was also used to assess for the presence of apathy to enable the examination of the convergent validity of the three versions of the AES (in contrast to the method of Marin et al.,

2 in which the correlations between the three versions of the AES were used as the only support for this important property of the scale). The NPI is an informant-based interviewer-administered scale developed by Cummings et al.

12,

13 to measure a range of behavioral disturbances, including delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, elation, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, aberrant motor behavior, sleep behavior and appetite behavior, in individuals with dementia.

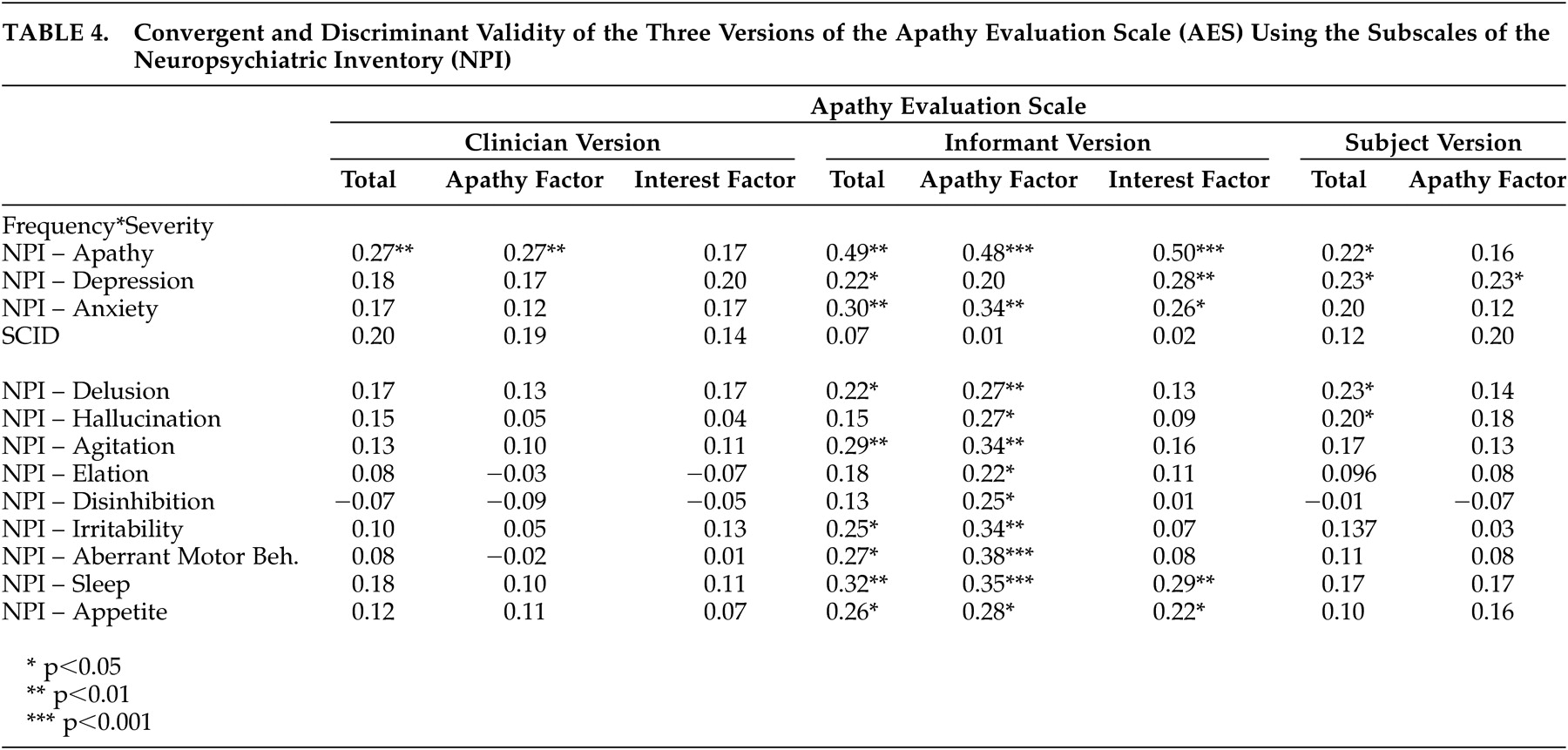

The other subscales of the NPI enabled the examination of the discriminant validity of the AES scales. For example, it was expected that apathy should not be highly correlated with the subscales if the scales had good discriminant validity, representing different constructs. The NPI is administered to a knowledgeable informant and inquires into the presence of the behavioral disturbances, and the frequency and severity of each disturbance.

12,

13 Severity is ranked on a three-point scale (1 to 3; mild, moderate, severe) and frequency on a four-point scale (1 to 4; occasionally, often, frequently, and very frequently).

12,

13 The NPI reportedly has good validity and reliability.

12 –

14 The depression portion of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)

15 was also used to assess for the presence of depression to further assess the discriminant validity of the AES. The SCID is a widely used semistructured interview for DSM diagnoses.

15Following the assessment of each participant by the behavioral neurologist, the psychiatrist, and neuropsychologist, as well as cerebral imaging that was ordered (i.e., computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and single photon emission computed tomography [SPECT] scans), the participant’s chart was reviewed to determine whether the individual met NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for possible or probable Alzheimer’s disease,

16 the Consortium on Dementia with Lewy Bodies criteria for dementia with lewy bodies,

17 the Lund and Manchester criteria for frontotemporal dementia

18 and/or the Hachinski criteria for vascular dementia.

19 Participants who met multiple diagnostic criteria received a diagnosis of mixed dementia.

Data Analysis

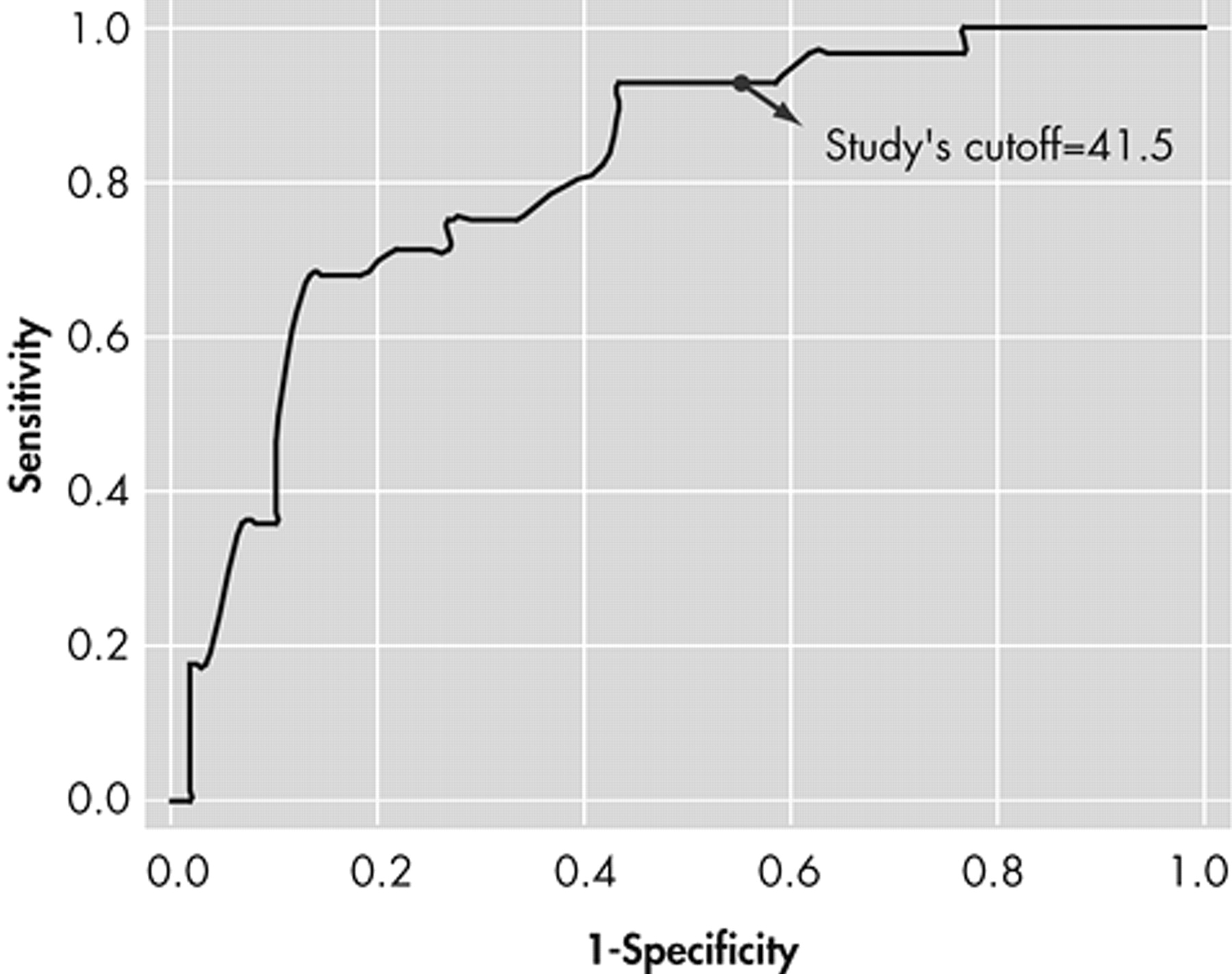

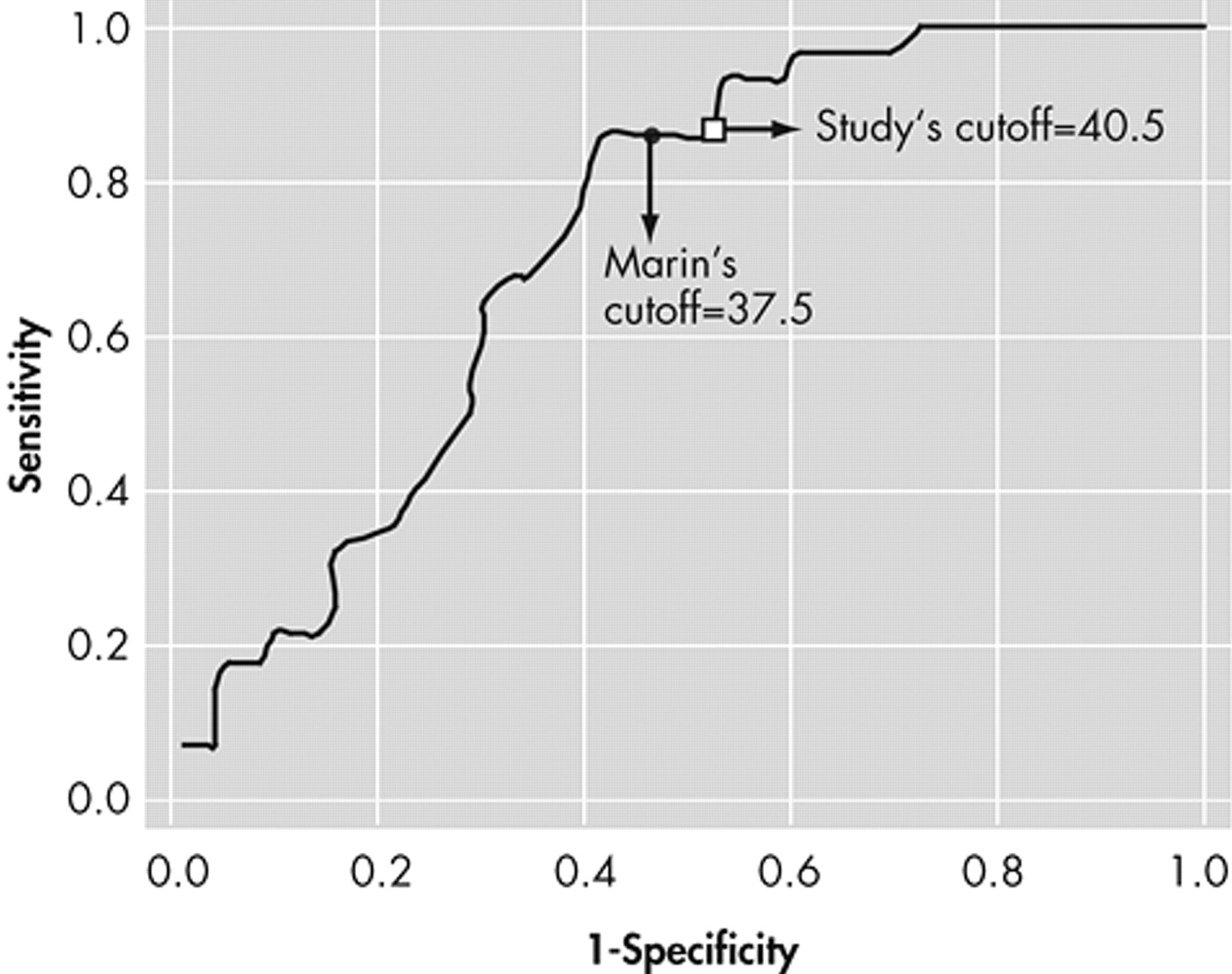

We conducted descriptive analyses to characterize the study sample, and exploratory factor analyses with principal axes factoring and varimax rotation methods to examine the factor structure of the AES. Sample size issues restricted the ability to conduct confirmatory factor analyses. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to determine the internal consistency of each identified factor. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were employed, using the psychiatrist’s diagnosis of apathy as the gold standard, to identify the cutoff scores for the three versions of the scales. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of each version of the AES were calculated. Correlational analyses were also conducted to investigate the convergent and discriminant validity of the AES. All analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 12.0.

20DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study relate to the factors identified as well as the optimal psychometric performance of the AES-I compared with both the AES-C and AES-S. However, it is important to note that this clinical investigation was prone to limitations as follows. There was a lengthy waiting list for the Behavioral Neurology Clinic, which might have led to a referral bias (e.g., there may have been a selection bias toward more diagnostically challenging or more difficult-to-manage cases being seen). We were also unable to maintain blindness of the psychiatrist to the results of the AES, and other neurobehavioral measures, as these were clinical data. These results might have influenced the psychiatrist’s diagnosis of apathy. As such, there is a need for a better gold standard for apathy in future studies that either examine the psychometric properties of the three versions of the AES or aim to develop new apathy scales. The AES-C and SCID were administered by the same clinical research assistant during the same interview session for each subject and results from one inventory may have influenced results from the others. Despite these limitations, this research has provided support for the internal consistency and the validity of the AES, particularly the informant and clinician versions. Another limitation to the study relates to the lack of information on ethnicity. Ethnicity has been found to be associated with apathy

21,

22 and therefore the lack of information on this variable possibly affected the results obtained.

Using the rule of a minimum of three items per factor, two factors were identified for each of the AES scales in this sample. These included factors of apathy and interest for the AES-C and AES-I, and apathy and “other” for the subject version of the scale. These results differed from those of Marin et al.

2 who identified three factors for the AES-C, two factors for the AES-S and one factor for the AES-I. However, the findings were also similar to the original study

2 in the identification of apathy and interest factors. For the AES-C, the items that loaded onto the apathy and interest factors were quite similar to the item loading shown in Marin et al.’s original study.

2 The items that loaded onto the apathy factor for the AES-C, AES-I, and AES-S were quite similar in this study, but three of the six items that loaded onto the interest factor of the AES-I were items that loaded onto the apathy factors of the AES-C and AES-S. These items were as follows: “S/he approaches life with intensity,” “S/he spends time doing things that interest her/him,” and “S/he has motivation.” At face value, the items appear to be related to apathy more so than interest. The validity of the second factor for the AES-S is questionable in that, at face value and theoretically, the items do not appear to be related, except for the fact that two of the three are the negatively worded items included in the scale.

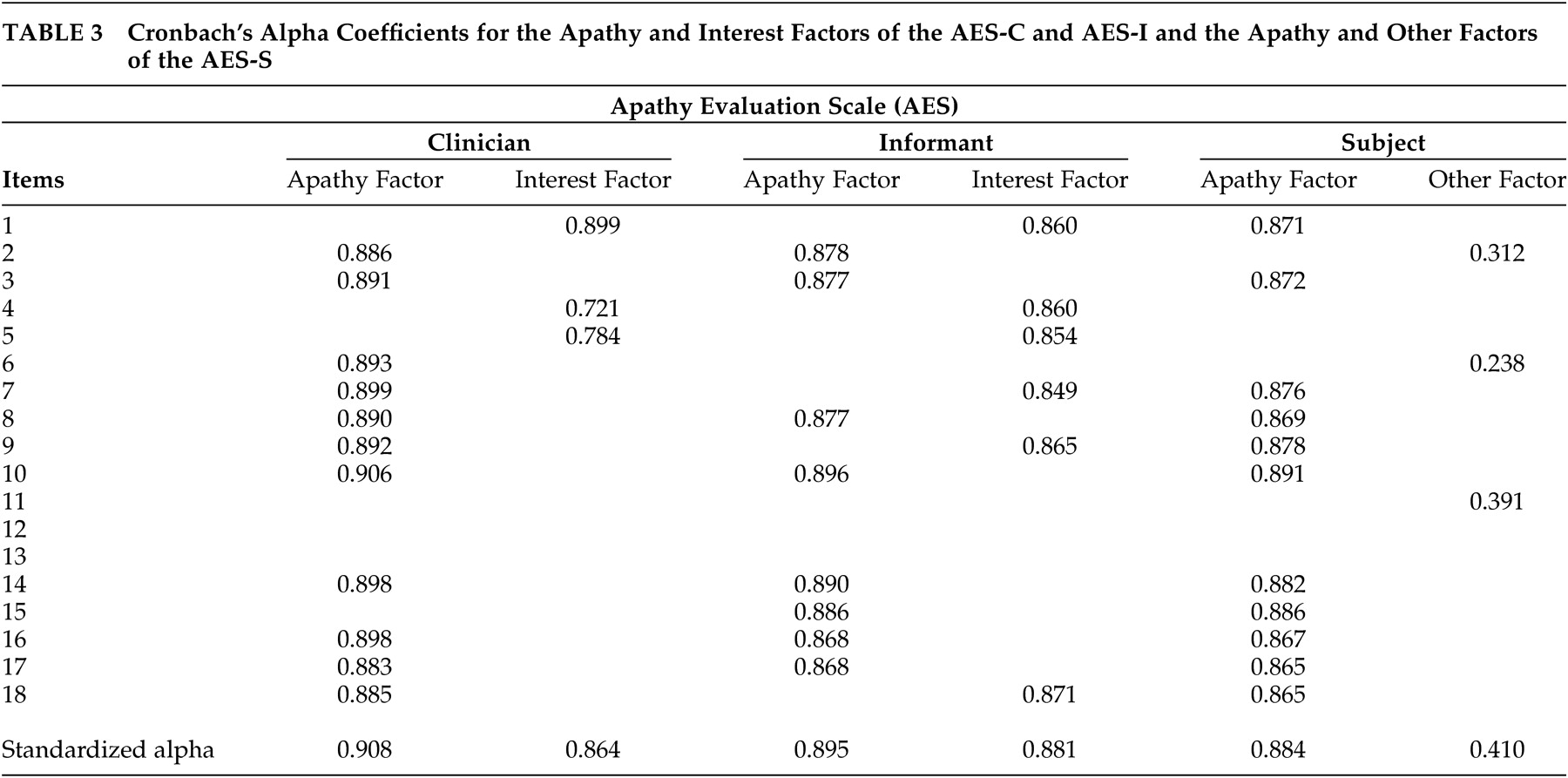

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients greater than or equal to 0.70 are said to be indicative of good internal consistency of a scale.

23 The observed Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.91, 0.86, and 0.90, 0.88 and 0.88 for the apathy and interest factors of the AES-C and AES-I, respectively, and the apathy factor of the AES-S indicated very good internal consistencies. However, the 0.41 Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the “other” factor of the AES-S indicated poor internal consistency. As such, it can be concluded that two reliable factors were identified for the AES-C and AES-I and one for the AES-S.

As with Marin et al.,

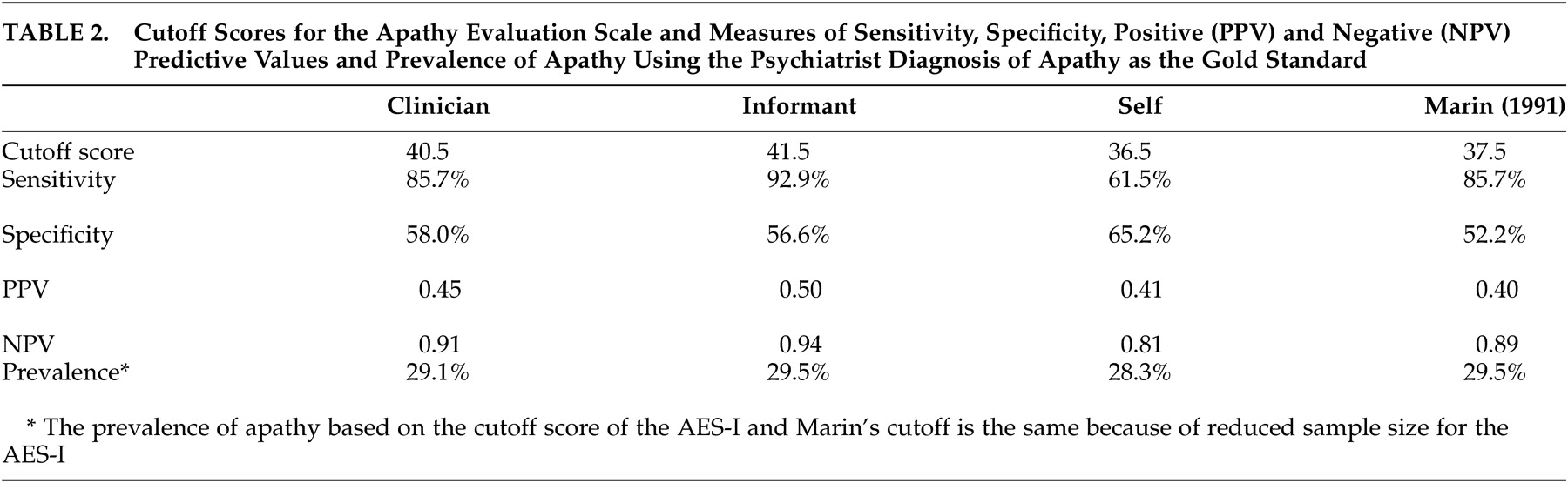

2 the AES-C was found to have fairly good psychometric properties. However, optimal psychometric performance was observed with the informant version of the AES. The cutoff score of 40.5 for the AES-C was higher than the score of 37.5 observed by Marin et al.,

2 and that of 38 observed by Pluck and Brown,

22 and is possibly a function of the differences in the makeup of the samples studied. Our cutoff score performed slightly better than that of Marin et al. with the same sensitivity (85.7) but slightly higher specificity (58.0 versus 52.2), positive predictive value (0.45 versus 0.40) and negative predictive value (0.91 versus 89.2). Marin et al.

2 had strict criteria for inclusion and exclusion for their study sample. This study, however, included a clinical population of patients who were all diagnosed with dementia and therefore were more likely to be impaired cognitively and functionally. As such, the cutoff score might appropriately be higher than that found using a “healthier” population. Pluck and Brown included only individuals with Parkinson’s disease who may or may not have had dementia.

24 This is the only study to date to provide a cutoff score for the informant version of the AES, which was one point higher than that of the clinician version.

The clinician version of the AES showed fair convergent validity by its statistically significant correlation with the apathy subscale of the NPI. The convergent validity of the AES-I appeared to be better than that of the AES-C and AES-S, but this could be due to the fact that both the AES-I and the apathy subscale of the NPI were informant-based and likely completed by the same informant. In contrast, the clinician version of the AES showed good discriminant validity by failing to have statistically significant correlations with the SCID depression, as well as the depression, anxiety, and other subscales of the NPI.

From a diagnostic point of view, the AES-I provided the greatest sensitivity as well as the strongest positive and negative predictive values. At a prevalence rate of 29.5% (based on the psychiatrist’s assessments), the combination of a high NPV and low PPV (0.5) suggests that the AES-I may be used clinically as a screening tool to rule out the presence of apathy when results are less than the cutoff score, and to encourage a clinician assessment when results are above the cutoff score. The AES-C and the AES-S do not appear to add diagnostically to the AES-I, and hence are probably unnecessary for clinical use.

It is important to note that the assessors who administered the clinician version of the AES had bachelor’s-level training in health-related fields with 1 to 5 years of experience working with dementia patients and more than 4 to 6 hours of experience with the scale, a criterion that Marin stated would be sufficient for reliable rating.

2However, it is possible that this level of training was not sufficient for reliable rating and might account for the less than optimal performance of the AES-C, a point raised in our critical appraisal of the AES-C. This “level of training” hypothesis could be investigated by comparing the rating of apathy with the AES-C across raters with different levels of training and experiences with the dementia population (i.e., interrater reliability), but this was not done in this current study. An alternate explanation for the less than optimal performance of the AES-C might be that the interviewer or rater needed to be someone who knew the patients well, or at least had time to observe the individuals’ behaviors in performing tasks that required initiative and self-motivation. This point was supported by the better performance of the AES-I. Therefore, in research settings where the research personnel or assessors have only bachelor’s-level training and less than 5 years of experience with dementia patients, it might be more appropriate to use the AES-I instead of the AES-C.