Apathy-Abulia

Apathy-abulia is the most common initial symptom of frontotemporal dementia and is present in the majority of patients as the disease progresses.

23,

28 –

33 Among frontotemporal dementia patients, clinicians often mistake as depression the presence of apathy, or the lack of feeling or emotion, and abulia, or the loss of volition and initiative.

28,

34 Miller et al.

21 initially reported two frontotemporal dementia patients with frontal hypoperfusion on single photon emission tomography (SPECT) who presented with “pseudodepression” attributable to apathy. The following year, Gustafson et al.

35 reviewed several hundred cases of dementias in a longitudinal prospective clinicopathological study. They identified 30 patients with frontotemporal dementia, all of whom developed apathy with amimia and mutism late in their course. In a careful retrospective review of nine patients with frontotemporal dementia, Galante et al.

36 confirmed that these patients became inactive with decreased behavioral initiation and spontaneity, loss of interest, and, ultimately, frank apathy. Eventually, several large series of outpatients, ranging from 50 to 74 patients, confirmed the presence of apathy-abulia in 62% to 89% of patients with frontotemporal dementia.

23,

37 –

39Comparative studies with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory show that apathy-abulia is more common, severe, and pervasive in frontotemporal dementia than in Alzheimer’s disease. Investigators developed the Neuropsychiatric Inventory to evaluate patients with Alzheimer’s disease on 12 behavioral features including delusions, hallucinations, agitation, dysphoria, anxiety, apathy, irritability, euphoria, disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior, night-time behavior disturbances, and appetite and eating abnormalities.

40 Levy et al.

41 first used the Neuropsychiatric Inventory to compare 22 patients with frontotemporal dementia with 30 patients with Alzheimer’s disease matched for dementia severity and found higher levels of apathy among those with frontotemporal dementia. Subsequently, Neuropsychiatric Inventory investigations reported apathy as one of the most common symptoms of frontotemporal dementia, present in approximately 95% of patients,

42,

43 more severe and frequent in frontotemporal dementia compared to Alzheimer’s disease,

44 –

46 and present in both mild and moderate-severe frontotemporal dementia.

47 Furthermore, in a discriminant analysis, Perri et al.

48 combined the Neuropsychiatric Inventory with neuropsychological testing to correctly assign 73.7% of 19 frontotemporal dementia patients and 94.7% of 39 Alzheimer’s disease patients based on better Rey’s Figure A Copy, worse performance on the Initial Letter Verbal Fluency Test (FAS), and greater Neuropsychiatric Inventory apathy subscale scores among the frontotemporal dementia patients.

Additional scales and measures have further defined the frequency and nature of apathy-abulia in frontotemporal dementia. Bozeat et al.

49 reported apathy among 75% of 33 frontotemporal dementia patients using their own neuropsychiatric caregiver questionnaire. Kertesz et al.

50 confirmed that apathy and aspontaneity distinguish frontotemporal dementia from non-frontotemporal dementia groups using the Frontal Behavior Inventory,

51 –

52 an instrument that they felt would be more sensitive to frontotemporal dementia than the Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

50 Others found significantly more apathy and negative symptoms in frontotemporal dementia than in Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, or mixed dementias.

53,

54 Rankin and colleagues

55 used the Interpersonal Adjectives Scales, a self-report and caregiver questionnaire, to measure personality change in 16 patients with frontal variant frontotemporal dementia (fvFTD), with greater frontal volume loss, and 13 with temporal variant frontotemporal dementia (tvFTD), with greater anterior temporal volume loss, and in a comparison group of 16 patients with Alzheimer’s disease. This, and a subsequent study with the Interpersonal Adjectives Scales, documented that fvFTD patients became aloof and introverted, unassured and socially submissive, and less dominant and assertive.

55,

56The presence of apathy-abulia in frontotemporal dementia correlates with orbitofrontal disease, extending from Brodmann’s area 10 to the anterior cingulate cortex, especially on the right. Liu et al.

57 studied 51 patients with frontotemporal dementia and 20 normal comparison subjects, as well as 22 patients with Alzheimer’s disease, using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory and MRI voxel-based morphometry. The fvFTD patients scored higher on apathy compared to the tvFTD patients or the Alzheimer’s disease patients. In voxel-based morphometry MRI studies, apathy scores on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory correlated not only with right lateral orbitofrontal atrophy but also with anterior cingulate cortex atrophy and, possibly, caudate head/ventral striatal atrophy.

58,

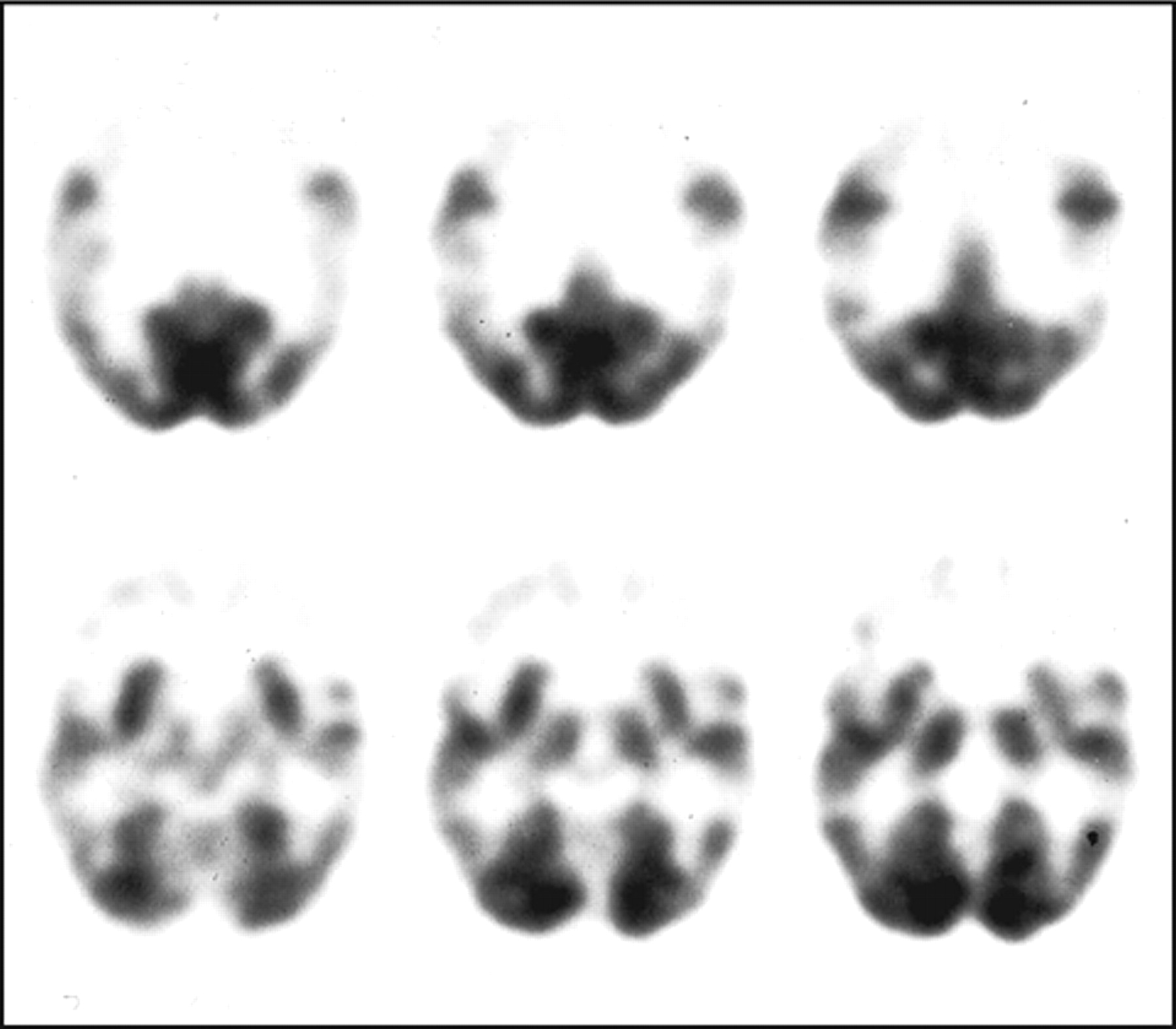

59 In SPECT and positron emission tomography (PET) studies, apathy in frontotemporal dementia correlated with right frontal hypoperfusion or frontal hypometabolism (

Figure 2 ).

30,

60 In addition, apathy in fvFTD may be associated with PET hypometabolism in the orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex.

31,

61 Investigators further reported orbitofrontal hypometabolism specifically in the right medial Brodmann’s area 10 associated with apathy in a range of frontal-predominant disorders.

62Disinhibition-Impulsivity

Disinhibition-impulsivity is one of two major behavioral subtypes of frontotemporal dementia, along with apathy-abulia.

30 –

32,

34,

63 It is unclear from the literature how often disinhibition and impulsivity are dissociable or occur independently in frontotemporal dementia. Many clinical and clinicopathological reports describe disinhibition and a decreased ability to restrain impulses as prominent and early symptoms of frontotemporal dementia.

2,

21,

35,

42,

61,

64 –

66 Among 63 frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients, Mourik et al.

43 described disinhibition in 52% of the patients on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory administered to their caregivers. Chow et al.

37 described disinhibition throughout the course of frontotemporal dementia among 62 patients evaluated retrospectively. Recently, Liscic et al.

67 reported their results on 48 autopsy-confirmed patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration compared to 27 autopsy-confirmed patients with Alzheimer’s disease. The frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients, most of whom had frontotemporal dementia, had much more disinhibition-impulsivity (23–25 patients; about 50%) compared to the Alzheimer’s disease patients (1–3 patients; 4–11%).

Comparative studies using scales and measures show that disinhibition-impulsivity discriminates frontotemporal dementia from other dementias. Multiple investigations using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory to compare frontotemporal dementia with Alzheimer’s disease show higher disinhibition scores among the frontotemporal dementia patients, particularly with fvFTD, compared to patients with Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and vascular dementia.

41,

44,

48,

57,

68,

69 Lopez et al.

70 evaluated DSM-III-R diagnoses in 20 patients with frontotemporal dementia and 40 patients with Alzheimer’s disease and found disinhibition in six frontotemporal dementia patients (30%) compared to only two Alzheimer’s disease patients (5%). Bathgate et al.

71 found greater disinhibition among 30 frontotemporal dementia patients compared to 75 Alzheimer’s disease and 34 “cerebrovascular dementia” patients on a semistructured caregiver questionnaire. Bozeat et al.

49 found greater group levels of disinhibition among 33 frontotemporal dementia patients compared to 27 Alzheimer’s disease patients using their neuropsychiatric questionnaire.

The presence of disinhibition-impulsivity correlates with right-sided frontotemporal disease. Miller et al.

65 described behavioral disinhibition as one of the dominant, and often first, symptoms in five patients with predominant right frontotemporal involvement, and, in a retrospective comparison of 52 patients with frontotemporal dementia and 101 patients with Alzheimer’s disease, Lindau et al.

64 found that disinhibition was greatest in the frontotemporal dementia patients with asymmetric right-sided involvement. In addition, Liu et al.

57 found that disinhibition on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory is associated with decreased right frontal volumes in frontotemporal dementia. In contrast, other investigations have described prominent disinhibited and impulsive behavior or frivolousness and inappropriate humor among frontotemporal dementia patients with bilateral or predominantly right anterior temporal involvement.

60,

72 –

75 Kertesz

28 suggested that the disinhibited subtype of frontotemporal dementia results specifically from both orbitofrontal and anterior temporal involvement. Consistent with this formulation, subsequent PET and voxel-based morphometry studies among disinhibited frontotemporal dementia patients show an interconnected right hemisphere region of involvement extending from the posterior orbitofrontal cortex, subgenu cingulate, to the anterior temporal pole.

1,

30,

31,

59,

61 This region may be somewhat more posterior than the region for apathy-abulia, but more research is needed to clarify this difference.

Loss of Insight and Self-Referential Behavior

Early in frontotemporal dementia, patients lose awareness of their disability or the consequences of their behavior and cannot see themselves from others’ point of view (perspective taking). Since being reported as part of the criteria for this disease,

5,

15,

38,

71,

76,

77 there have been many clinical reports on loss of insight in frontotemporal dementia. Among 53 frontotemporal dementia patients, Mendez and Perryman

23 reported loss of insight in 58.5% at onset and in 100% 2 years later. Similarly, Passant et al.

25 found loss of insight in all 19 of their neuropathologically verified cases with frontotemporal dementia. Perrine et al.

78 showed loss of insight in frontotemporal dementia associated with loss of perspective taking (i.e., they cannot show how others see them). More recently, Evers et al.

79 evaluated the decreased insight in five of eight patients with frontotemporal dementia and suggested that there was primarily a loss of “emotional insight” from frontotemporal disease, rather than impairment in “cognitive insight.” This loss of emotional insight resembles more of an anosodiaphoria, or indifference towards their illness rather than a true anosognosia, or ignorance of their symptoms.

80In comparative studies, the loss of insight or self-awareness is worse in frontotemporal dementia than in other dementia syndromes. Eslinger et al.

81 used the Brock Adaptive Function Inventory and Apathy Evaluation Scale to evaluate 27 frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients, 11 Alzheimer’s disease patients, and 11 comparison subjects. Their frontotemporal dementia sample as a whole showed significantly less behavioral self-awareness and self-knowledge than the Alzheimer’s disease and healthy comparison samples. Pijnenburg et al.

82 retrospectively reviewed the case notes of 46 patients diagnosed with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (21 with frontotemporal dementia). In contrast to the other patients, the majority of the frontotemporal dementia patients presented without complaints or awareness of symptoms. Moretti et al.

83 compared frontotemporal dementia versus vascular dementia (subcortical) and found that frontotemporal dementia had a total lack of insight, whereas it was more intact in vascular dementia. Finally, O’Keeffe et al.

84 investigated loss of insight in 14 frontotemporal dementia patients compared to 11 corticobasal degeneration and 10 progressive supranuclear palsy patients. Although all groups had decreased insight, the frontotemporal dementia patient group was most impaired in “emergent awareness” or detection of their errors.

The loss of insight in frontotemporal dementia is part of a spectrum of loss of self-referential behaviors such as self-consciousness, self-perception, stable self-concepts, self-criticism or reflection, awareness of personality changes, or self-conscious responses.

56,

78,

80,

81 Snowden et al.

32 characterized frontotemporal dementia patients as lacking self-conscious emotions, and Bathgate et al.

71 characterized frontotemporal dementia patients as selfish. Using an autobiographical memory task, Piolino et al.

85 found a group deficit of autonoetic consciousness (self-perception) in 15 fvFTD patients. In a unique report, Miller et al.

86 showed that stable self-concepts, such as religion and political affiliation, can be altered with the development of frontotemporal dementia. Rankin et al.

56 used the Interpersonal Adjectives Scales to compare self-awareness of personality and personality changes in 12 fvFTD patients, 10 patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and 11 comparison subjects. In this and other studies, the frontotemporal dementia patients exaggerated positive qualities, minimized negative ones, and were generally unaware of their personality change (or current personality).

56,

81 Finally, Sturm et al.

87 examined the response of 30 frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients and 23 cognitively normal comparison subjects to a loud, unexpected acoustic startle stimulus (115-dB burst of white noise). Results indicated that frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients and comparison subjects had similar responses to the startle except for significantly fewer facial signs of embarrassment or self-conscious responses among the frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients.

The presence of loss of insight and self-referential behavior correlates with right frontal involvement in frontotemporal dementia.

86 On SPECT scans of frontotemporal dementia patients, loss of insight is associated with hypoperfusion in the right hemisphere, particularly the frontal lobe.

60,

80 Furthermore, loss of insight was significantly more common with right (54.6%) versus left (13.9%) temporal atrophy;

88 however, involvement of the left temporal lobe may result in anosognosia for their social disability. Sturm et al.’s

87 findings are consistent with neural loss in the medial prefrontal cortex, which may play an important role in the production of self-conscious emotions as self-awareness activates the medial prefrontal cortex during active recollection of one’s past and during passive self-reflection.

87 Finally, a recent multi-center study of lack of awareness in frontotemporal dementia compared to Alzheimer’s disease suggested that greater loss of awareness in frontotemporal dementia corresponds to the degree of frontally-mediated atrophy.

89Decreased Emotion and Empathy

In general, frontotemporal dementia patients lack emotional warmth and appear emotionally shallow and indifferent.

32,

65,

90,

91,

92 In a large series, Le Ber et al.

61 document changes in affect and emotional development among patients with frontotemporal dementia, and Snowden et al.

32 found that emotional unresponsiveness, including reduced response to pain, was pervasive among frontotemporal dementia patients. Using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, a measure of cognitive and emotional empathy, Lough et al.

93 reported decreased empathic concern and decreased perspective taking in frontotemporal dementia, and Eslinger et al.

94 reported decreased self-awareness of empathy. In experiments, the emotional deficit in frontotemporal dementia spares emotional reactivity and the recognition of happiness, but impairs the recognition of negative emotions such as sadness and fear and the experience of self-conscious emotions such as embarrassment and shame.

78,

90In comparative studies, emotional blunting and loss of empathy are worse in frontotemporal dementia than in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Among 30 patients with frontotemporal dementia and 30 patients with Alzheimer’s disease, Miller et al.

46 reported more patients with emotional unconcern in the frontotemporal dementia group (N=24, 80.0%) compared to the Alzheimer’s disease group (N=6, 20.0%).

46 Barber et al.

95 found less emotional reaction to handicaps on a retrospective informant questionnaire in 18 subjects with pathologically proven frontotemporal dementia than in 20 subjects with Alzheimer’s disease. Likewise, among 30 frontotemporal dementia patients, 75 Alzheimer’s disease patients, and 34 vascular dementia patients, Bathgate et al.

71 reported greater loss of emotions among the frontotemporal dementia patients. Two studies that used the Scale for Emotional Blunting recorded higher emotional blunting scores in frontotemporal dementia than in Alzheimer’s disease.

53,

75 Two other studies using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index reported significantly more impaired cognitive (perspective taking) and emotional (emotional contagion) empathy in frontotemporal dementia compared to other dementia groups.

96,

97In frontotemporal dementia, decreased empathy is associated with right anterior temporal disease. Case studies or series of tvFTD found loss of empathy, fixed facial expressions unresponsive to situations, and emotional distancing and blunting, particularly with right-sided disease,

72,

73,

98,

99 and the speech of right hemispheric frontotemporal dementia patients was less relevant to emotionally loaded pictures than that of left hemisphere patients.

100 In studies using the Interpersonal Adjectives Scales or the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, Rankin et al.

55 showed that tvFTD patients were particularly prone to interpersonal coldness compared to fvFTD patients and had decreased emotional contagion or emotional response to another’s distress.

97 On voxel-based morphometry MRI, empathy correlated with a right medial frontotemporal network, particularly emotional empathy with the right ventromedial and anterior temporal areas.

96,

97 Moreover, among artists with predominant right temporal frontotemporal dementia, Mendez and Perryman

101 report decreases in empathy reflected in alterations in their caricatures of others, and, using distorted and morphed face tasks, Mendez and Lim

102 showed that frontotemporal dementia patients with predominant right frontotemporal involvement tended to have decreased empathic awareness.

Violation of Social and Moral Norms

Frontotemporal dementia patients have disturbed social and moral behavior. Social changes that differ from the patient’s premorbid behavior most commonly include social inadequacy or awkwardness, tactlessness, disagreeableness, decreased propriety and manners, unacceptable physical contact, or improper verbal or physical acts.

15,

23,

36,

64,

103 In a retrospective study of 19 neuropathologically verified patients with frontotemporal dementia, Passant et al.

25 found impaired social interactions in all patients, including offensive language in ten, physical aggression in eight, and many traffic violations. Mychack et al.

104 found that 11 of 12 right-sided and two of 19 left-sided frontotemporal dementia patients had socially undesirable behavior, such as criminality or socially deviant acts, as an early presenting symptom of frontotemporal dementia. Frontotemporal dementia patients may engage in minor theft or shoplifting,

76,

105 driving violations,

106 inappropriate sexual behavior,

65,

107,

108 and acts of violence.

76 Miller et al.

109 found antisocial behavior in nearly 50% of patients with frontotemporal dementia, including stealing, hit and run accidents, physical assault, indecent exposure, sexual comments or advances, and public urination. Edwards-Lee et al.

73 described the stealing of small objects in six out of ten tvFTD patients.

Comparative studies indicate that social and moral behavioral changes can differentiate frontotemporal dementia from other dementias. Bozeat et al.

49 found that loss of social awareness helps differentiate frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease, and Shinagawa et al.

33 found that changes in social behavior were more common initial symptoms in patients with frontotemporal dementia than in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or semantic dementia. A comparison of 21 frontotemporal dementia patients with 11 vascular dementia patients with a dominating frontal lobe syndrome found significantly less social awareness among the frontotemporal dementia patients.

110 Sociopathic acts are also more prominent in frontotemporal dementia compared to Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia illnesses.

46,

105,

108 Mendez et al.

111 reported that 16 frontotemporal dementia patients (57%) had sociopathic behavior, compared to only two Alzheimer’s disease patients (7%), and Diehl et al.

105 reported misdemeanor violations in 15 frontotemporal dementia patients (50%), compared to only one Alzheimer’s disease patient (3%). Finally, Mendez et al.

112 administered an inventory of moral knowledge and moral dilemmas to 26 patients with fvFTD, 26 patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and 26 normal control subjects.

113 Although all groups had knowledge of moral behavior, only the frontotemporal dementia patients were impaired in their ability to make immediate, emotionally based moral judgments.

In frontotemporal dementia, disturbed social and moral behavior correlates with right ventromedial-orbitofrontal-amygdalar disease. Miller et al.

114 suggested that the right hemisphere primarily controls social conduct in frontotemporal dementia, and various investigations have shown greater right-sided changes with social behavioral changes in frontotemporal lobar degeneration.

46,

54,

71,

81,

88,

98,

99,

102,

111,

115,

116 Sarazin et al.

62 studied 32 patients with frontal lobe pathologies with PET and found that hypometabolism, predominantly in the right orbitofrontal region, corresponded to an indifference to rules. Decreased agreeableness on the NEO Five-Factor Inventory in frontotemporal dementia also correlates with right orbitofrontal changes.

103 More recently, Nakano et al.

117 correlated antisocial behavior in frontotemporal dementia with decreased blood flow in the orbitofrontal cortex. In sum, frontotemporal dementia affects a socio-moral network that includes the right ventromedial region, which, as previously seen, emotionally tags social and moral situations (reexperiencing previously learned emotional responses in novel situations), the orbitofrontal cortex, which responds to social cues and mitigates impulsive reactions, and the amygdalae, which are necessary for threat detection and moral learning.

78,

93,

113Changes in Dietary or Eating Behavior

Early changes in dietary and eating behavior are a common manifestation of frontotemporal dementia and include a spectrum from patients altering their dietary preferences to placing nonfood items in their mouths, consistent with the Klüver-Bucy syndrome.

35,

118 Frontotemporal dementia patients develop gluttony, sweets and carbohydrate craving, increased weight, obsessions with particular foods, and occasional alcoholism.

Eating behavior changes occur in almost 80% of frontotemporal dementia patients.

47 Miller et al.

21 suggested that hyperorality was one of the most discriminating aspects of frontotemporal dementia, and, in an early clinicopathological study, Mendez et al.

2 described hyperoral behavior as one of the distinguishing features of frontotemporal dementia. Among 19 neuropathologically verified frontotemporal dementia cases, Passant et al.

25 found that 14 patients had alterations in dietary or oral behavior including two who started to drink alcohol. Other reports on frontotemporal dementia described hyperorality,

39 gluttony and indiscriminate eating,

32,

71,

119 sweet food preferences,

71,

119 and changes in eating behaviors or eating disorders.

45,

49 Snowden et al.

32 found that gluttony and early increased appetite, indiscriminate eating, and sweet cravings were the most characteristic dietary or oral symptoms of frontotemporal dementia,

120 whereas patients with semantic dementia were more likely to exhibit food fads or early changes in food preferences.

88,

120 Finally, the Klüver-Bucy Syndrome, with generalized and potentially fatal hyperorality, is distinct from the other dietary and oral behaviors and only occurs in a minority of advanced frontotemporal dementia patients with bilateral temporal involvement.

32,

118,

121Comparative studies show that frontotemporal dementia patients have more changes in dietary or eating behavior than patients with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. Miller et al.

122 queried the primary caregivers of 14 patients with frontotemporal dementia and 14 patients with Alzheimer’s disease on the occurrence of weight gain and sweet and carbohydrate craving. Weight gain in frontotemporal dementia patients amounted to 64% and carbohydrate craving was 79%, compared to 7% and 0%, respectively, for Alzheimer’s disease. Ikeda et al.

120 investigated the frequency of changes in eating behaviors in fvFTD (N=23), semantic dementia (N=25), and Alzheimer’s disease (N=43) using a caregiver questionnaire of swallowing problems, appetite change, food preference, eating habits, and other oral behaviors and found that the frequencies of symptoms in all domains except swallowing problems were higher in fvFTD than in Alzheimer’s disease. Srikanth et al.

69 compared 23 frontotemporal dementia patients, 44 Alzheimer’s disease patients, and 31 vascular dementia patients on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory and found that mean abnormal scores in the domain of appetite/eating behavior helped differentiate frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Recently, in Liscic et al.’s

67 clinicopathologic series, the 48 frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients had more hyperorality (N=6, 12.5%) than the 27 Alzheimer’s disease patients (0%).

In frontotemporal dementia, dietary or eating behavioral disturbances correlate with disease affecting lateral orbitofrontal cortex, especially on the right, and adjacent structures, especially the insula. In Neuropsychiatric Inventory studies of frontotemporal dementia, Liu et al.

57 showed that eating disorders correlated with frontal lobe involvement, and Short et al.

123 showed a right rather than a left frontal association with hyperphagia among 59 frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. Rosen et al.

59 found that eating disorders were more specifically associated with changes in the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, ventral anterior cingulate cortex, and adjacent subfrontal gyrus, caudate head/ventral striatum, and insula. More recently, Whitwell et al.

124 differentiated carbohydrate cravings and hyperphagia in a voxel-based morphometry study of 16 frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients compared to nine normal control subjects. The development of a pathological sweet tooth was associated with gray matter loss in posterior lateral orbitofrontal cortices (Brodmann’s area 12/47) and right anterior insula, whereas the development of hyperphagia was associated with gray matter loss in anterolateral orbitofrontal cortices (Brodmann’s area 11). Seeley et al.

72 suggested that altered food preferences result from orbitofrontal derailment of satiety centers or from processing of insular disgust signals.

Repetitive Behaviors

Investigators have documented a range of repetitive behaviors in frontotemporal dementia.

15,

35,

41,

65,

122,

125 –

127 Repetitive behaviors encompass simple repetitive acts and verbal or motor stereotypies such as lip smacking, hand rubbing or clapping, counting aloud, and humming. Repetitive behaviors also encompass complex repetitive motor routines such as counting, checking, cleaning, wandering a fixed route, repetitive trips to the bathroom, collecting and hoarding objects, pathological gambling, and rituals involving touching, grabbing, and superstitious acts.

21,

114,

126 –

128 Stereotypies or compulsive acts are often among the earliest and most salient presenting symptom of frontotemporal dementia and can be bizarre and severely disabling.

23,

33,

65,

122Similar to dietary and eating behaviors, about 80% of frontotemporal dementia patients eventually have repetitive behaviors,

125 which is more than in other dementias. Miller et al.

21 suggested that the best discriminants for frontotemporal dementia were stereotypical and perseverative behaviors along with hyperorality and loss of hygiene, and these investigators further reported repeated compulsive behaviors in 64% of frontotemporal dementia patients compared to 14% of Alzheimer’s disease patients.

122 Gustafson et al.

35 reviewed several hundred clinicopathological cases of dementia and concluded that frontotemporal dementia was a slowly progressive dementia characterized by stereotypy. Mendez et al.

126 evaluated compulsive behaviors as presenting symptoms in 29 patients with frontotemporal dementia compared to 48 patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Compulsive behaviors occurred in 11 frontotemporal dementia patients (38%) versus five Alzheimer’s disease patients (10%). Other repetitive behaviors reported in frontotemporal dementia include compulsive hoarding, pathological gambling, and self-injurious behaviors such as trichotillomania, picking at fingers to the point of excoriation, and self-biting.

25,

129The few studies that have used specific behavioral scales for repetitive behaviors have documented motor and verbal stereotypies as well as compulsions in frontotemporal dementia.

34,

42,

49,

52,

71,

130 Shigenobu et al.

131 developed the Stereotypy Rating Inventory, which evaluates eating and cooking behaviors, roaming, speaking, movements, and daily rhythm; and assessed 26 frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients, 46 Alzheimer’s disease patients, 26 vascular dementia patients, and 40 normal controls subjects. The frontotemporal lobar degeneration group scored much higher on this instrument than all the other groups. Nyatsanza et al.

132 used the Stereotypic and Ritualistic Behavior subscale, an addendum to the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, to assess 18 fvFTD, 13 semantic dementia, and 28 Alzheimer’s disease patients. Both the fvFTD and the semantic dementia patients scored significantly higher on this subscale than the Alzheimer’s disease patients. Mendez et al.

133 used a stereotypy scale to evaluate 18 frontotemporal dementia and 18 Alzheimer’s disease patients. Of the frontotemporal dementia patients, eight had stereotypical behaviors (44.4%), such as frequent rubbing and self-injurious acts, compared to only one of the Alzheimer’s disease patients (5.6%). In addition, all of the frontotemporal dementia patients with stereotypical movements had compulsive-like behaviors, suggesting a similar pathophysiological cause.

In frontotemporal lobar degeneration, simple stereotypies correlate with right frontal involvement and complex compulsions with temporal involvement. The occurrence of stereotypies correlates with hypometabolism in the right orbitofrontal region, an area which regulates stimulus reinforcement associated with learning aberrant motor behavior.

62 Rosen et al.

59 further showed that the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, and insula, along with adjacent motor regions, participate in planning of motor acts in frontotemporal dementia. Consistent with this finding, McMurtray et al.

60 reported that the presence of right frontal hypoperfusion on SPECT predicted stereotyped behaviors in frontotemporal dementia. In contrast to simple verbal or motor stereotypies, frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients with complex compulsive behavior, or intentional and time-consuming repetitive acts, appear to have temporal lobe involvement.

32 Rosso et al.

134 found complex compulsions in 18 of 90 patients with frontotemporal dementia (21%) and an association between temporal lobe atrophy and complex compulsions. Others corroborate an association of prominent rigidity, complex compulsions, and a preoccupation with puzzles among patients with temporal predominant frontotemporal lobar degeneration.

72,

88 Finally, some complex compulsions, such as pathological gambling, may require additional disinhibition from involvement in the adjacent orbitofrontal cortex.

135Psychotic Symptoms

Clinicians can confuse frontotemporal dementia with schizophrenia or atypical psychosis, particularly when frontotemporal dementia occurs at a young age.

9,

136 –

139 Delusional thoughts and hallucinations, however, are uncommon manifestations of frontotemporal dementia, particularly in comparison to Alzheimer’s disease.

4 A review of the world’s literature found 18 well-documented patients with possible frontotemporal dementia and delusions or hallucinations,

140 –

146 but only two cases were truly suggestive of this association. Miller et al.

65 and Edwards-Lee et al.

73 reported a 56-year-old woman who believed that she had contracted AIDS through her husband, became depressed, and showed severe hypoperfusion in the right frontal and temporal region and mild left frontotemporal hypoperfusion. Her subsequent course was consistent with frontotemporal dementia, but no pathology was reported. In a strong case for psychosis in frontotemporal dementia, Reischle et al.

147 reported a 53-year-old man with acute auditory and bizarre visual hallucinations with euphoria and self-overstimulation. Remission of the psychotic symptoms unmasked the clinical picture of a rapidly progressive frontotemporal dementia supported by the results of cerebral MRI and PET, but without pathological confirmation.

Although frontotemporal dementia can mimic schizophrenia,

38 the few psychiatric series suggest that frontotemporal dementia rarely manifests as psychosis. Among 68 fvFTD patients, only 5% had delusions and 2% had hallucinations.

61 Using the Comprehensive Psychiatric Rating Scale, Gregory

130 failed to find psychosis among 15 fvFTD patients. Although Gregory and Hodges

24 did not find psychosis in their prospective evaluation of 15 frontotemporal dementia patients, in their retrospective of 12 patients, one had been incorrectly diagnosed with a schizophreniform psychosis. Confirming frequent misdiagnoses during life, Passant et al.

25 found that most of their 19 autopsy-verified frontotemporal dementia patients had had an initial psychiatric diagnosis, including four with psychosis or schizophrenia, but on further review, none of these patients had actually manifested delusions or hallucinations.

In clinical reports, the prevalence of psychosis in frontotemporal dementia is much lower than in Alzheimer’s disease and appears overestimated with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. Levy et al.

41 found delusions on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory in five of 22 frontotemporal dementia patients (23%) and 10 of 30 Alzheimer’s disease patients (33%), and Liu et al.

57 found delusions on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory in five of 23 fvFTD patients (22%) and five of 26 tvFTD patients (19%). Levy et al.

41 found hallucinations in none of the frontotemporal dementia patients and two of the Alzheimer’s disease patients (7%), and Liu et al.

57 found hallucinations in three of the fvFTD patients (13%) and none of the tvFTD patients. Using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, Lopez et al.

70 also found much more delusional psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease than in frontotemporal dementia, and Hirono et al.

68 confirmed that there were fewer delusions in frontotemporal dementia compared to Alzheimer’s disease. Mourik et al.

43 initially reported delusions on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory in eight of 63 frontotemporal dementia patients (12.7%), along with four with hallucinations (6.3%), but it turned out that none of these patients had true “delusions” when specifically evaluated and queried. Finally, in Liscic et al.’s

67 clinicopathologic series, the 48 frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients had fewer hallucinations than the 27 Alzheimer’s disease patients (zero versus four, or 15%). Parenthetically, other investigators suggest that although delusions and hallucinations are rare in frontotemporal dementia, a low B

12 level may correlate with hallucinations in frontotemporal dementia.

54,

148Mood Disorders

Depressive symptoms occur in frontotemporal dementia. In early studies, Gustafson

107 reviewed the longitudinal course of 20 frontotemporal dementia patients and noted brief depressive reactions, and Miller et al.

21 reported that two of eight patients (25%) presented with depression. In autopsy-confirmed studies, Gustafson

76 found depressive episodes with occasional suicidal ideation and euphoria among 30 cases, and Mendez et al.

2 found depression among two of 21 frontotemporal dementia patients. Using the Comprehensive Psychiatric Rating Scale, Gregory

130 found three fvFTD patients out of 15 who reported sadness, but only one met criteria for DSM-IV major depressive episode. Among 63 frontotemporal dementia patients evaluated with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, Mourik et al.

43 found depression in 10 cases (16%). Multidimensional scaling revealed a Cluster A was comprised of delusions, hallucinations, irritability, and agitation, and a Cluster B represented depression and anxiety. In some cases, depression may be a prodrome of frontotemporal dementia and a possible familial risk factor.

24,

144,

149 –

152Depression in frontotemporal dementia has atypical features. Lopez et al.

70 prospectively evaluated DSM-III-R diagnoses in 20 patients with frontotemporal dementia (six autopsy-proven) ascertained by psychiatrists using a structured clinical interview and compared them to 40 patients with Alzheimer’s disease. The frontotemporal dementia patients had higher scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and exhibited significantly more DSM-III-R major depression (N=5, 25%) than the Alzheimer’s disease patients (N=2, 5%). However, among the frontotemporal dementia patients, only 40% expressed depressed mood, sleep disturbances were found in 30%, appetite changes in 25%, and low self-esteem in 10%, while irritable mood was found in 80% of patients, anergia in 75%, social withdrawal in 70%, psychomotor retardation in 35%, and suicidal ideation in 20%. Swartz et al.,

153 using the Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry in a retrospective chart review, found that early episodic lability, sadness, anhedonia, increased appetite, loss of interest, and social withdrawal were common among 19 frontotemporal dementia patients, but hopelessness and suicidal ideation occurred in less than half, and themes of guilt were absent.

The relative prevalence of depression in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease may depend upon how depression is ascertained. Using their caregiver questionnaire, Bozeat et al.

49 found that mood changes in general were equally prevalent in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease and covaried with disease severity. Other investigations with other means or instruments have shown less depression, and possibly more euphoria, in frontotemporal dementia versus Alzheimer’s disease and most other dementias.

41,

95,

149,

154 –

156 Using caregiver questionnaires and interviews, Barber et al.

95 found that mood changes were significantly more common in 20 Alzheimer’s disease than in 18 frontotemporal dementia patients. Snowden et al.

149 summarized their experiences in caring for approximately 200 frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients (40 autopsy-proven), and compared with approximately 400 patients with Alzheimer’s disease, depression was less common in frontotemporal dementia. Mendez et al.

154 found positive ratings on the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease (BEHAVE-AD) affective disturbances subscale in 25% of 29 frontotemporal dementia patients, compared to 38% of 29 Alzheimer’s disease patients, and Chiu and colleagues

157 did not find significant differences in the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease affective disturbances subscale between frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies. In two studies using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (154 patients), Levy et al.

41,

156 found that patients with frontotemporal dementia had lower levels of depression or dysphoric mood (39%) than did those with Alzheimer’s disease (43%), Parkinson’s disease (55%), and Huntington’s disease (71%), but not progressive supranuclear palsy (18%). In addition, a neuropsychological study of 40 frontotemporal dementia patients and 40 subcortical vascular dementia patients found milder depressive symptoms in frontotemporal dementia than in vascular dementia.

83In addition to depression, euphoria, hypomania, emotional lability, childish excitement, and acquired extroversion can occur in the context of frontotemporal dementia and can mimic bipolar disease.

2,

21,

46,

65,

75,

158 In a longitudinal series of 20 patients with frontotemporal dementia,

107 euphoria occurred in 35% and ranged between 30% and 36% in two studies that used the Neuropsychiatric Inventory,

41,

43 and Levy et al.

41 found that euphoria was more common in frontotemporal dementia (36% of 22 patients) compared to Alzheimer’s disease (7% of 30 patients). Although mania has not yet been reported in frontotemporal dementia, McMurtray et al.

60 reported hypomania-like behavior among tvFTD patients, and Thompson et al.

88 found hypomania retrospectively in 2.8% of 36 patients with left-lateralized tvFTD and 9.1% of 11 patients with right-lateralized tvFTD. The hypomanic patient in the latter study appeared to be elated with mild pressured speech and flight of ideas. Emotionalism or lability may occur in some patients with frontotemporal dementia.

15,

76,

159 Finally, peurile, childish, frivolous, or silly behavior occurs with right temporal, and probably adjacent orbitofrontal, involvement

75 and can be associated with moria, or foolish or silly euphoria, and Witzelsücht, or a tendency to tell inappropriate jokes.

74Depression correlates with severe left frontotemporal disease, especially with temporal involvement, whereas other emotional disturbances correlate with early right temporal disease. In the study of Bozeat et al.,

49 depression was present in 45% of their tvFTD patients but only 7% of their fvFTD patients. Similarly, Chow and Mendez

160 found depression in 19% of 16 patients with frontotemporal dementia, compared to 44% of nine patients with semantic dementia. Among tvFTD patients, Edwards-Lee et al.

73 found typical depression (anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, crying) in two of five left tvFTD patients and none of five right tvFTD patients using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. In contrast, among 74 frontotemporal dementia patients, McMurtray et al.

60 found hypomanic-like behavior associated with temporal hypoperfusion on SPECT, and Mendez et al.

75 found dysthymia and anxiety associated with right temporal hypoperfusion.

Anxiety, Irritability, and Aggression

Anxiety symptoms, usually assessed with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, may be more frequent among frontotemporal dementia patients than has been previously appreciated. In Lopez et al.’s

70 study, 45% of their 20 frontotemporal dementia patients had anxiety, compared to only 10% of their 40 Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neuropsychiatric Inventory studies show more anxiety in patients with fvFTD than those with tvFTD or Alzheimer’s disease.

43,

57 Porter et al.

161 specifically assessed the prevalence of anxiety among 115 patients with Alzheimer’s disease, as compared with 33 patients with frontotemporal dementia, 43 patients with vascular dementia, and 40 normal control subjects. Anxiety was significantly more common in patients with frontotemporal dementia and vascular dementia than in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. More recently, Le Ber et al.

61 evaluated 68 frontotemporal dementia patients and reported anxiety symptoms in 15% of them. Among frontotemporal dementia patients, anxiety correlated with right temporal hypoperfusion,

60 and increased neuroticism and personal distress correlated with right temporal atrophy.

99 Finally, several investigators have commented on the presence of hypochondriacal complaints among frontotemporal dementia patients.

15,

35,

41,

65,

76,

130Irritability and aggression are systematically described in only a few publications on frontotemporal dementia. Mendez et al.

154 applied the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease rating scale and found more anger and aggressive outbursts in frontotemporal dementia compared to Alzheimer’s disease, and Lopez et al.

70 evaluated DSM-III-R diagnoses and found significantly more irritability and agitation in frontotemporal dementia compared to Alzheimer’s disease. Passant et al.

25 reported physical aggression and signs of hostility in eight of their 19 neuropathologically confirmed frontotemporal dementia patients. Edwards-Lee et al.

73 described irritability and aggressive behavior as particularly associated with right temporal involvement, but Thompson et al.

88 indicated that irritability was more common in left than in right temporal frontotemporal lobar degeneration.

Additional Behaviors with Limited Literature

Common additional noncognitive behaviors in frontotemporal dementia and related syndromes include declines in hygiene and self-care, behavioral eccentricities, fixed stare and/or smile, aberrant motor behavior, sleep disturbances, and increased artistic creativity. Most of these behaviors are difficult to entirely distinguish from previously discussed neuropsychiatric features of frontotemporal dementia; however, criteria and investigators have specifically referred to these behaviors as characteristic of this disorder. Loss of hygiene and self-care are common in frontotemporal dementia but are difficult to dissociate from apathy-abulia, disinhibition-impulsivity, and loss of insight and self-referential behavior. Several investigators have emphasized the eccentric behaviors that can emerge, particularly in right tvFTD, including bizarre alterations in mode of dress and marked changes in religious or political orientation.

73,

86 An “alien stare” or peculiar physical bearing (sustained stare or fixed fatuous smile) is associated with right frontotemporal disease.

75 Affect in frontotemporal dementia is sometimes jocular and facial expressions are often fatuous with grinning and inappropriate giggling.

149 Many of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory studies describe aberrant motor behavior in patients with frontotemporal dementia as compared to other conditions,

41,

43,

44,

48,

57,

68,

69 but these can be repetitive stereotypies or compulsions, disinhibition-impulsivity, irritability, or other behaviors. Finally, Liu et al.

57 described sleep disturbances in tvFTD and among 47 semantic dementia patients, and Thompson et al.

88 described those with predominant right-side involvement as more prone to sleep problems.

One of the most interesting and intriguing behavioral changes among frontotemporal dementia patients is an increase in artistic creativity. Several case reports describe an increase in primarily visual artistic performance among well-diagnosed patients with frontotemporal dementia.

162 –

166 These authors suggest the possibility of a release of perceptual abilities with progressive impairments of language and other left hemisphere functions.