Group I Studies

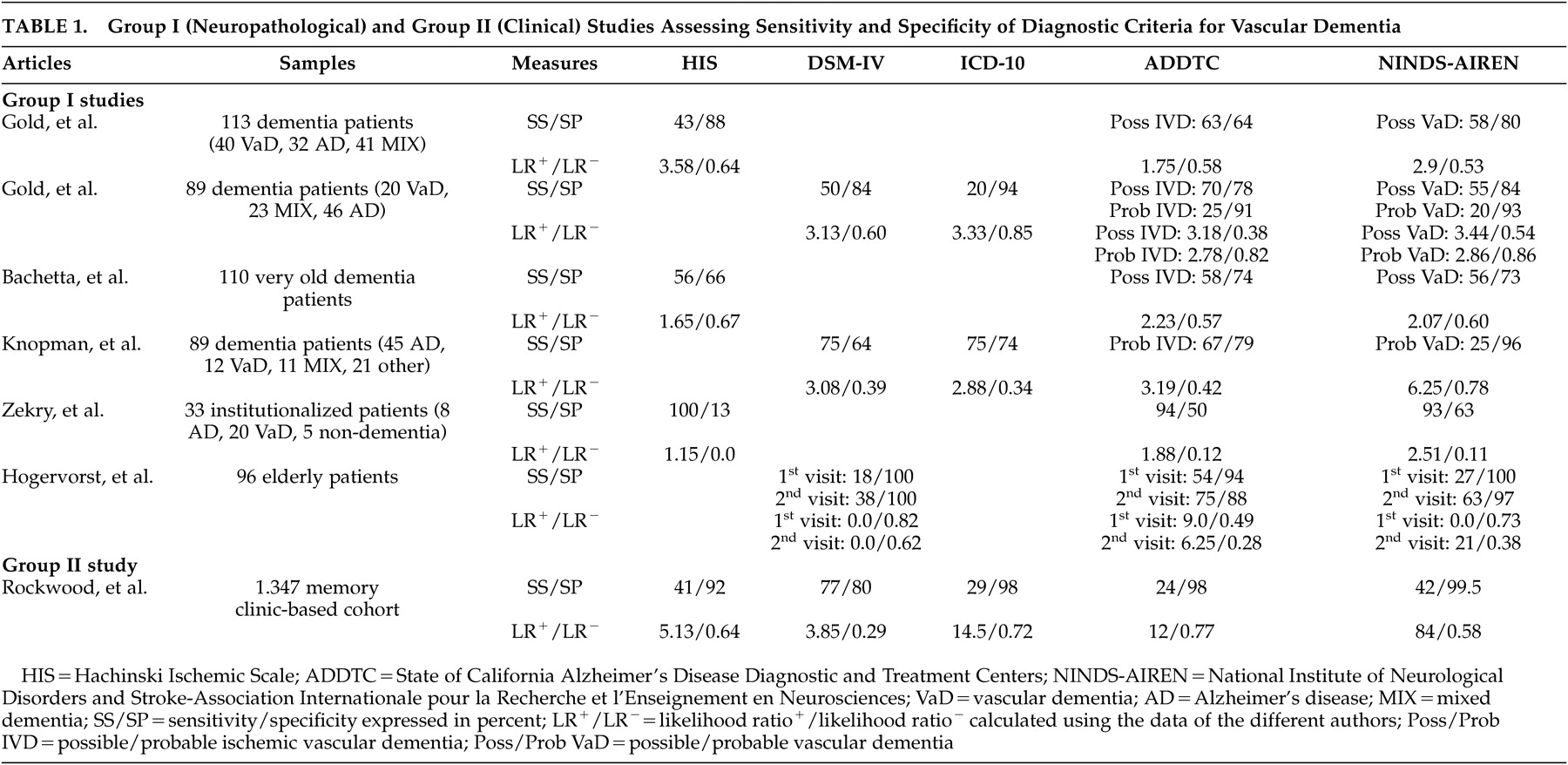

Six articles pertained to this first group, which specifically assessed the sensitivity and specificity estimates of various sets of criteria for vascular dementia using a neuropathological confirmation of diagnosis (

Table 1 ). The sample size varied from 33 to 113 autopsied cases, and the analyses were generally performed retrospectively. The Ischemic Scale of Rosen, DSM-III, and DSM-III-R criteria have not been investigated and therefore are not illustrated in

Table 1 . The principal finding was that the other criteria yield relatively low sensitivity, but high specificity. The main limitation was related to the type of vascular lesions considered by the authors. In the absence of widely accepted markers of vascular dementia (as underlined as a critical issue in Part I of the review), teams of authors developed and used their own neuropathological markers of vascular dementia. These various and different neuropathological definitions prevent accurate comparisons between the reviewed studies and constitute one of the principal limitations of group I studies. Interestingly, the calculated positive likelihood ratios revealed that most diagnostic criteria generate only a minimal to small increase in the likelihood of having vascular dementia (LR

+ between 0 and 3.58). However, the ADDTC and NINDS-AIREN criteria demonstrated a moderate to large increase in the likelihood of having vascular dementia (LR

+ values between 6.25 and 21), respectively. According to the LR

− values, the capacity of the different sets of criteria to properly identify the true negatives was not very successful, since the LR

− values were all higher than 0.1 (except for the Hachinski Ischemic Scale in the study of Zekry et al.

11 ).

The first group I study was performed by Gold et al. in 1997.

12 These authors performed a clinico-neuropathological study comparing the sensitivity and specificity estimates of the ADDTC, the NINDS-AIREN, and the Hachinski Ischemic Scale criteria for the diagnosis of possible vascular dementia on 113 autopsied patients with dementia. They found that the Hachinski Ischemic Scale was the most specific, but the least sensitive, set of criteria, while the ADDTC criteria were the most sensitive. Moreover, the sensitivity/specificity figures for the differential diagnosis between vascular dementia and mixed dementia were 30%/97% for the Hachinski Ischemic Scale, 43%/91% for the NINDS-AIREN, and 58%/88% for the ADDTC criteria. The ADDTC criteria thus reached the best balance between sensitivity and specificity for the differential diagnosis of mixed dementia. The three criteria sets successfully differentiated vascular dementia from Alzheimer’s disease patients since only 3.5% (Hachinski Ischemic Scale), 9.4% (NINDS-AIREN), and 12.7% (ADDTC) of the cases were misclassified as vascular dementia instead of Alzheimer’s disease. Nevertheless, in the absence of neuroimaging data, these findings were limited to the clinical criteria for possible (and not probable) vascular dementia. In a later study, this same group investigated the sensitivity and specificity estimates of the NINDS-AIREN, ADDTC, DSM-IV, and ICD-10 criteria for the diagnosis of possible and probable vascular dementia in 89 dementia patients for whom cerebral imaging data (CT scan or MRI) were available within 6 months of their death.

13 Neuropathological examination was conducted at autopsy. The most sensitive criteria for possible vascular dementia were the ADDTC criteria, followed by the NINDS-AIREN criteria, and DSM-IV. The most specific criteria for probable vascular dementia were the ICD-10, ADDTC, and the NINDS-AIREN criteria. These authors also showed that the proportion of neuropathologically confirmed Alzheimer’s disease cases clinically misclassified as vascular dementia ranged from 0% (ICD-10) to 13% (ADDTC), whereas the proportion of the neuropathologically confirmed cases of mixed dementia clinically misclassified as vascular dementia ranged from 9% (ADDTC probable vascular dementia) to 39% (ADDTC possible vascular dementia). Therefore, the application of the ADDTC criteria resulted in a high rate of misclassification when mixed cases were considered.

More recently, the same team of researchers provided the first neuropathological validation of the criteria for vascular dementia in a hospital-based cohort composed of the oldest-old patients.

14 The authors analyzed 110 autopsied cases of dementia over 90 years of age and reported comparably low sensitivity rates between the Hachinski Ischemic Scale, the ADDTC, and NINDS-AIREN criteria for possible ischemic vascular dementia/vascular dementia (from 56% to 58%). More than 40% of the neuropathologically confirmed vascular dementia cases were not identified by any of the clinical criteria studied. In regards to specificity, the Hachinski Ischemic Scale was the least specific. Both the NINDS-AIREN and ADDTC criteria performed very well at excluding Alzheimer’s disease. However, 30% of the mixed dementia cases were misdiagnosed by the ADDTC and NINDS-AIREN criteria, whereas up to 45.9% of mixed dementia cases were erroneously diagnosed as having pure vascular dementia by the Hachinski Ischemic Scale. Some limitations should nevertheless be mentioned concerning these three studies.

12 –

14 First, they were conducted on hospital-based cohorts, and hence were not representative of the full spectrum of patients with vascular dementia. The studies did not clearly specify what kind of cognitive assessment was performed to define dementia. The studies only mentioned a mental state examination—insufficient to properly characterize the cognitive syndrome. Furthermore, in the absence of widely accepted quantitative neuropathological criteria for vascular dementia and to guarantee that the dementia in this context was related to a predominant vascular pathology, the studies applied a restricted definition of significant vascular lesions. This was based on the presence of a lacunar state in the basal ganglia or on both macroscopic and microscopic cortical infarcts involving at least three cortical association areas (excluding the primary and secondary visual cortex). Vascular lesions confined to subcortical structures other than the basal ganglia were not considered for a diagnosis of vascular dementia. In this respect, the findings of these studies concerned the validity of diagnostic criteria for the detection of multi-ischemic dementia, but not other forms of vascular dementia, such as Binswanger’s subcortical encephalopathy, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, dementia linked to hypoperfusion, and hemorrhagic dementia.

Knopman et al.

15 retrospectively identified incident cases of dementia from the Rochester Epidemiology Project in order to investigate clinico-pathological correlations of vascular dementia. Of 482 incident cases of dementia, 419 were deceased at the time of their study, and neuropathological diagnoses were available in 89 cases. The best sensitivity rates were obtained with the ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria, whereas the worst rates were achieved with the NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia. Conversely, the NINDS-AIREN were the most specific, and the DSM-IV the least specific criteria. The lack of sensitivity of the diagnostic criteria for pure vascular dementia was due to five patients (of 12 cases) with pure vascular dementia at neuropathological examination who lacked a temporal relationship between clinical stroke and onset of their dementia. Only half of the subjects with radiological evidence of critical ischemic lesions in fact had a history of clinical stroke or focal motor signs. This study was principally limited by its retrospective collection of data, which may have led to high rates of dementia diagnoses; the lack of details about the cognitive tests they used to determine the presence of dementia; and by the lack of independence between the clinical and pathological diagnosis. Moreover, patients with a temporal relationship between dementia and stroke tended to undergo autopsy more frequently than did others, and autopsied patients had two or more strokes more often than did the nonautopsied patients. This situation may not be representative of all cases of vascular diseases associated with dementia. Since only a few patients of the total cohort underwent routine autopsy, their estimates of sensitivity and specificity might have been biased. However, this limitation is quite common in any autopsy study.

Zekry et al.

11 carried out a prospective clinico-neuropathological study of 33 institutionalized patients age 75 years and over. Although all sets of criteria were highly sensitive, the Hachinski Ischemic Scale was the most sensitive set of criteria for vascular dementia (100%) but, conversely, the least specific compared to the NINDS-AIREN and ADDTC clinical criteria for vascular dementia/ischemic vascular dementia. In addition, the most sensitive criteria for diagnosing pure versus mixed cases were still the Hachinski Ischemic Scale (86%), and the most specific were the NINDS-AIREN (63%). The best diagnostic agreement between clinical criteria and the neuropathological examination was observed when all cases of mixed dementia were excluded (88%), demonstrating that this diagnosis was clinically underestimated. Thus, Zekry et al.

11 concluded that all sets of criteria distinguished pure Alzheimer’s disease from vascular dementia with a high accuracy whereas mixed dementia remained problematic. However, this study was performed on a small sample of patients (N=33), which was not representative of the general population because of a selection bias. This bias might have explained why the sensitivity rates were so high and so different from the other studies reviewed herein. A psychometric battery and scales were used for the diagnosis of dementia and therefore to describe the cognitive syndrome, but the authors did not clearly specify them. In addition, they did not take into account subcortical vascular lesions in their neuropathological diagnosis; only bilateral infarcts and unilateral infarcts involving the territories of either the posterior or anterior cerebral artery were felt to be consistent with the diagnosis of vascular dementia.

The last clinico-pathological study was conducted by Hogervorst et al.

16 on 96 elderly dementia patients and control subjects as part of the Oxford, England, Project to Investigate Memory and Ageing (OPTIMA) longitudinal study. The definition of dementia was based on a brief scale (i.e., Mini-Mental State Examination) and global scales (i.e., Clinical Dementia Rating and the Cambridge Examination for Mental Disorders of the Elderly). Although the primary goal was to investigate the validity and reliability of the clinical criteria for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia using a computerized “dementia diagnosis system,” the study also reported sensitivity and specificity results for various sets of clinical criteria. In particular, they found that none of the criteria for vascular dementia (using the DSM-IV, ADDTC, and NINDS-AIREN criteria) at the first clinical visit had very good sensitivity for predicting autopsy findings, despite excellent specificity. However, with clinical data from follow-up visits, reasonable sensitivity and specificity were obtained with the ADDTC criteria compared with the NINDS-AIREN and DSM-IV criteria. This study included only a small sample of patients with cerebrovascular disease and vascular dementia (N=11). Moreover, for postmortem confirmation of cerebrovascular disease or vascular dementia, the authors only included dementia patients with moderate to severe cerebrovascular disease with or without additional (non-Alzheimer’s disease) pathology at autopsy. In these cases, cerebrovascular disease was substantial when consisting of either multiple infarcts and/or cribriform (or lacunar) state accompanied by surrounding tissue rarefaction and gliosis or white matter myelin pallor. In these cases, vascular disease was considered to have contributed to the dementia to varying extent.

To summarize, these data revealed that the ADDTC criteria for

possible ischemic vascular dementia achieved the best balance of sensitivity and specificity. Nevertheless, there was a marked age-related decrease in the sensitivity rates of the ADDTC criteria for

possible ischemic vascular dementia.

14 The sensitivity rates of the NINDS-AIREN criteria for

possible vascular dementia and the Hachinski Ischemic Scale were higher in the oldest-old cohort or comparable to those reported in the old population by previous studies.

12 –

14 The NINDS-AIREN criteria were consistently found to be the most specific criteria. However, the results of Bacchetta et al.

14 compared to those of other researchers also revealed a decrease in the specificity rates of all three sets of criteria compared to those reported in the younger elderly cohort.

12,

13 In addition, the data of Hogervorst et al.

16 suggested that a 6-month follow-up visit may be useful to increase both sensitivity and specificity rates of the vascular dementia criteria. In regards to the likelihood ratios, most studies demonstrated that the diagnostic criteria did not reach the threshold values for acceptance of a diagnostic test (LR

+ >10 and LR

− <0.1).

9,

17 In fact, only the NINDS-AIREN criteria showed, in two different studies,

15,

16 a moderate to large increase in the likelihood of having vascular dementia (LR

+ values between 6.25 and 21), whereas the ADDTC criteria showed a moderate increase in the likelihood of having vascular dementia (LR

+ values between 6.25 and 9) in only one study.

16Group II Studies

Two studies (one clinical and one clinico-neuropathological) were included in this group. The DSM-III and DSM-III-R criteria were again not investigated. The clinical study by Rockwood et al.

18 yielded rather different results compared to those found in the group I studies. The neuropathological study by Fischer et al.

19 was limited to the ischemic scales, and thus could not be comprehensively compared to the group I studies. Overall, the DSM-IV criteria were found to be the most sensitive, and the NINDS-AIREN criteria were found to be the most specific. The ischemic scales gave high rates of misclassification (vascular dementia instead of Alzheimer’s disease). The only group II study which addressed the question of sensitivity and specificity of clinical criteria was performed by Rockwood et al.

18 in a multicenter prospective cohort study design (

Table 1 ). Compared with the clinical judgment of geriatricians and neurologists (the “gold standard” used in this study), who diagnosed 101 out of 1347 participants with vascular dementia, the NINDS-AIREN criteria were found to be the most specific. The DSM-IV criteria were the most sensitive, while, in contrast to the above studies, the ADDTC criteria were the least sensitive. Thus, the DSM-IV identified the greatest numbers of patients as having vascular dementia. However, lower proportions of these individuals had vascular risk factors and focal neurological signs compared with those identified by other criteria. The analysis of the cerebral imaging data revealed that greater proportions of ADDTC classified patients showed a multi-infarct profile, whereas white matter changes were more common among those diagnosed by the DSM-IV. In general, neuroimaging was felt to change the final diagnosis in 10.8% of patients. Rockwood et al.

18 concluded that consensus-based criteria for vascular dementia omitted patients who did not meet dementia criteria modeled on Alzheimer’s disease. Even for patients who did meet these criteria, the proportion identified with vascular dementia varied widely. Interestingly, the clinical judgment of clinicians was also compared with the various diagnostic criteria sets in 324 out of 1347 participants diagnosed with vascular cognitive impairment. They found the following sensitivity and specificity rates: 14%/99% (NINDS-AIREN); 14%/99% (ADDTC); 13%/99% (ICD-10); 53%/85% (DSM-IV); and 29%/96% (Hachinski Ischemic Scale). Once again, the DSM-IV criteria were the most sensitive and the NINDS-AIREN and ADDTC criteria were the most specific. However, values above the threshold for the positive likelihood ratio were obtained only by the NINDS-AIREN, the ICD-10, and ADDTC criteria, respectively (

Table 1 ), indicating better diagnostic capacity of these criteria over the DSM-IV. One major limitation of this study was a selection bias, since the patient sample came from a memory clinic and thus was not representative of the entire population. This cohort may have included a higher number of cases with mixed dementia, because, according to the authors, mixed dementia is more likely to be diagnosed as vascular cognitive impairment in memory clinics. Moreover, they only relied on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and some other functional scales to determine the presence or absence of dementia. The conclusions of this study were further limited because clinicians used their clinical judgment as the gold standard to compare the diagnosis of vascular dementia with the consensus diagnostic criteria. Nevertheless, their prevalence results were similar to previous clinical work (see group III studies).

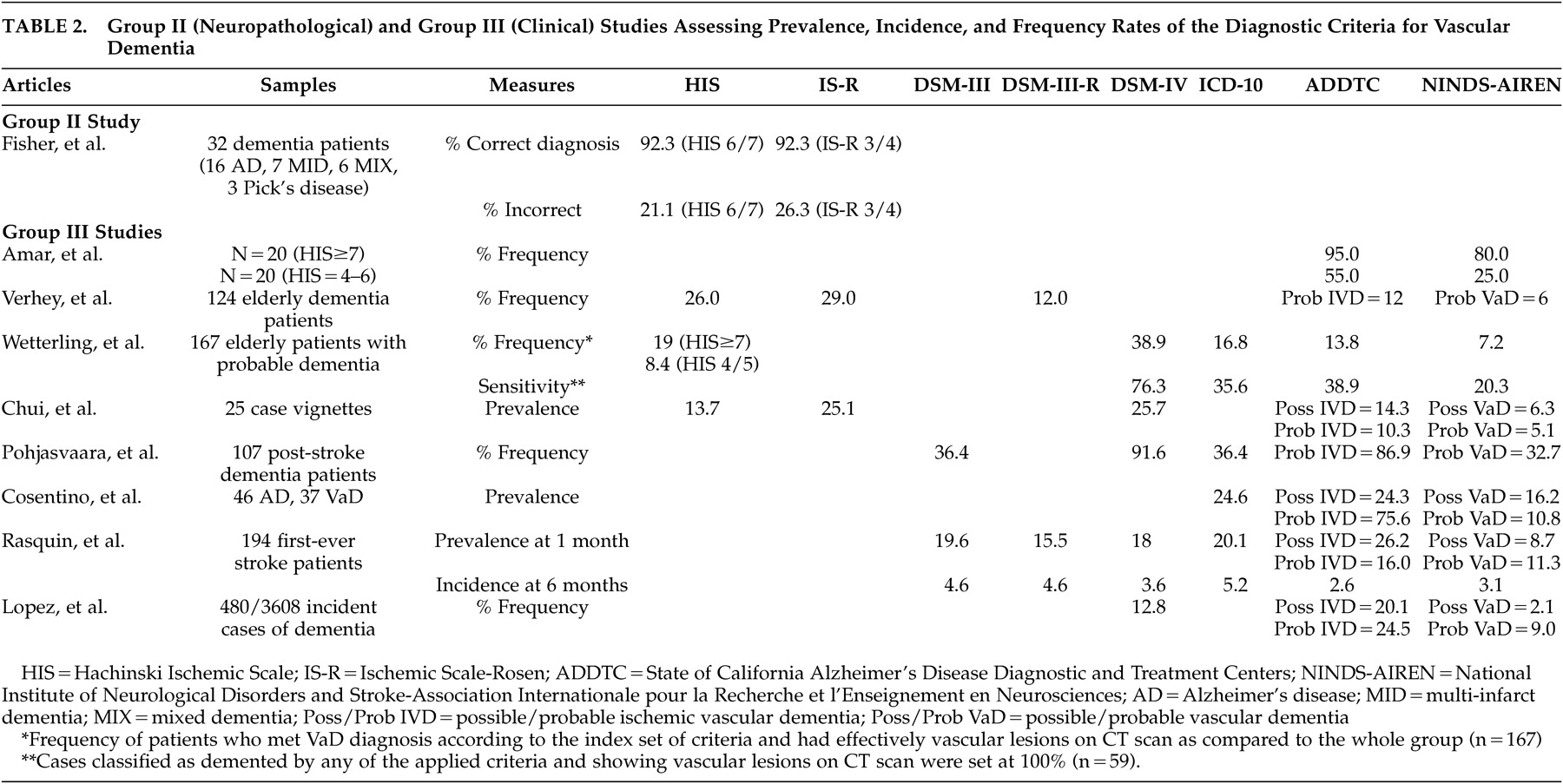

The next group II study was a prospective clinico-neuropathological study that did not specifically address the question of sensitivity and specificity (

Table 2 ). It aimed instead at validating the Hachinski ischemic scales in a consecutive series of 32 elderly demented patients, as determined by a score lower than 24 on the MMSE, who had a neuropathological confirmation of their diagnosis.

19 The authors found that the Hachinski ischemic scales were able to diagnose mixed dementia (coexistence of Alzheimer’s disease and multi-ischemic dementia) and multi-ischemic dementia correctly in 92.3% of cases, independent of the cutoff and scoring system used. However, there was a high rate of false positive cases in individuals who had been clinically diagnosed as having mixed dementia or multi-ischemic dementia, but were found to have Alzheimer’s disease at autopsy. The results of this study should be interpreted with caution given the very small sample size.

Group III Studies

Eight clinical studies pertained to this group (

Table 2 ). The studies generally aimed at determining prevalence/incidence or frequency rates of vascular dementia according to different criteria. The sample sizes varied from 25 to 480 cases according to the type of experimental design (case vignette analysis versus longitudinal multicenter study). Overall, these studies suggested that the ADDTC criteria led to the highest proportion of vascular dementia diagnosis whereas the NINDS-AIREN criteria led to the lowest proportion. However, false positive diagnoses of vascular dementia were most frequent when the ADDTC criteria were used.

Amar et al.

20 retrospectively applied the NINDS-AIREN and the ADDTC criteria to two groups of patients who underwent a relatively detailed neuropsychological examination and who were thought to be suffering from vascular dementia per their initial scores on the Hachinski Ischemic Scale. The first group (N=20) had a high Hachinski Ischemic Scale score of ≥7, and the second group (N=20) had a score between 4 and 6. The authors found the ADDTC to be the most sensitive criteria as they yielded the highest proportion of vascular dementia diagnosis. However, this study was limited by the small sample size and the lack of distinction between diagnoses of possible or probable vascular dementia.

Verhey et al.

21 studied 124 dementia patients from a memory clinic and found that frequency values of vascular dementia were the highest with the ischemic scales: the Ischemic Scale of Rosen resulted in nearly five times as many patients with vascular dementia as when the NINDS-AIREN criteria were applied. Only eight patients fulfilled all criteria sets. The authors concluded that the criteria sets could not be interchanged. However, they noticed that in clear-cut patients, as defined by clear evidence of multiple strokes by history, clinical examination, and CT scans, different criteria led to similar diagnoses. The criteria diverged when information from one category did not confirm the other (e.g., when there was evidence of stroke on CT scan without focal neurological symptoms or vice versa). This study also showed that if a temporal connection and/or neuroimaging data were taken into account, the diagnostic outcome was considerably different. Unfortunately, the authors did not mention what kind of cognitive assessment they performed in order to reach the diagnosis of vascular dementia.

Wetterling et al.

22 studied 167 patients admitted for probable dementia. The authors found that 109 patients met at least one of four definitions for dementia (either ICD-10, DSM-IV, ADDTC, or NINDS-AIREN criteria). However, only 59 of these patients (54.1%) showed vascular lesions on a CT scan. Among them, 74.6% had bilateral vascular lesions and 42.2% had pure white matter lesions. Small-vessel disease was the most frequent type of lesion seen on CT (48.6%), while large-vessel infarcts were the second most frequent type of lesion (11.9%). Approximately 5.5% of patients presented with small and large vessel lesions. Of the 65 cases meeting the DSM-IV criteria for vascular dementia, only 69% had vascular lesions on a CT scan. Of the 28 cases meeting the ICD-10 criteria for vascular dementia, 75% had vascular lesions on a CT scan. In order to evaluate the sensitivity values of the four diagnostic criteria sets, the diagnoses of dementia according to any of these clinical criteria were contrasted with the vascular lesions on a CT scan (considered as the “gold standard”). The DSM-IV criteria were the most sensitive criteria for vascular dementia (the NINDS-AIREN was the least sensitive), but their specificity rate was the lowest as CT scans revealed no vascular lesions in 30.8% of cases. In fact, a high proportion of patients also fulfilled the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for Alzheimer’s disease (or other sets of criteria for Alzheimer’s disease).

With regards to concordance, Wetterling et al.

22 found that 86.4% of their patients were diagnosed with vascular dementia by at least one of the four diagnostic criteria, but only five cases met the criteria for vascular dementia according to all the diagnostic criteria. These five subjects were characterized by large-vessel infarcts involving cortical areas, three or more focal neurological signs, and a stepwise deterioration. Finally, the findings occurring in less than one third of the sample included evidence of two or more strokes, evidence of two or more infarcts on CT scan, a history of multiple transient ischemic attack, and focal neurological symptoms. It should be mentioned that the patients in this study were only administered very short scales (i.e., MMSE) and a structured interview to determine the presence of dementia.

Chui et al.

23 aimed at assessing concordance in classification, as well as the interrater reliability, for different clinical criteria of vascular dementia using 25 case vignettes representing a spectrum of cognitive impairment (21 out of 25 case vignettes had information regarding cognitive tests) and subtypes of dementia. They found that the DSM-IV and the Ischemic Scale of Rosen were the most liberal criteria. The ADDTC criteria, as well as the Hachinski Ischemic Scale, produced an intermediate frequency of vascular dementia, while the NINDS-AIREN criteria were the most conservative. The interrater reliability was the highest for the Hachinski Ischemic Scale (κ=0.61), and was the lowest for the ADDTC for possible vascular dementia (κ=0.15). Interrater reliability for the NINDS-AIREN for probable or possible vascular dementia was intermediate (κ=0.42).

Pohjasvaara et al.

24 studied 107 dementia patients who underwent a very comprehensive neuropsychological battery following an ischemic stroke and demonstrated that the number of cases classified as vascular dementia according to the different criteria varied considerably. Consistent with previous studies, the DSM-IV criteria were found to be the most sensitive, while the NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia were the least sensitive. Only 31 patients (29%) fulfilled all criteria sets for vascular dementia, and only 40 patients (37.4%) showed focal neurological signs on neurological examination 3 months after their stroke. Patients with small-vessel subcortical vascular dementia frequently did not show clear-cut focal neurological signs. However, this study included only poststroke patients and excluded other types of vascular diseases.

More recently, Cosentino et al.

25 retrospectively analyzed a series of ambulatory patients who also underwent an extensive neuropsychological assessment. Thirty-seven patients were diagnosed with vascular dementia (per a multidisciplinary team diagnosis) and 46 patients with Alzheimer’s disease (per a multidisciplinary team diagnosis and the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria). Most of the patients met the ADDTC criteria for probable ischemic vascular dementia in contrast to the NINDS-AIREN; very few patients met the latter criteria. However, the ADDTC criteria for probable ischemic vascular dementia were the only criteria resulting in false positive diagnosis of vascular dementia; 15.2% of Alzheimer’s disease patients also met the criteria for probable ischemic vascular dementia. Moreover, only 45.9% of cases with vascular dementia were diagnosed by more than one diagnostic scheme. Regardless of the diagnostic scheme that was used, Cosentino et al.

25 demonstrated that the most common clinical characteristics associated with vascular dementia were hypertension; neuroradiological evidence of extensive periventricular and deep white matter alterations; and differential impairment on neuropsychological tests assessing visuoconstruction and the ability to establish and maintain mental set, with relatively higher scores on tests of memory using the delayed recognition paradigm. In fact, there was a double dissociation as the Alzheimer’s disease patients presented the inverse neuropsychological profile. The authors thus suggested that these features could perhaps be utilized as indicators of vascular rather than Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the future.

Rasquin et al.’s study

26 aimed at determining, in a sample of 194 first-time stroke patients, the influence of different diagnostic criteria on the prevalence and cumulative incidence of poststroke dementia using a longitudinal design as clinically evaluated at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months after stroke. The authors used an extensive cognitive battery in patients whose MMSE score was higher than 15. The highest prevalence rate of dementia at 1 month was obtained using the ADDTC criteria (for possible ischemic vascular dementia) and the ICD-10 criteria, and the lowest prevalence rate was obtained using the NINDS-AIREN criteria (for both possible and probable vascular dementia). The incidence rates were highest at 6 months, ranging from 2.6% (ADDTC) to 5.2% (ICD-10).

Finally, Lopez et al.

27 classified 480 incident cases of vascular dementia from the multicenter Cardiovascular Health Study–Cognition Study. In this study, patients were administered an extensive neuropsychological battery as well as a brain MRI during their follow-up. The authors aimed at comparing and contrasting the diagnosis of vascular dementia based solely on history of strokes or severe vascular disease versus that aided by neuroimaging. The pre-MRI classification showed that of 480 incident cases, 52 participants (10.8%) had vascular dementia and 76 (15.8%) had both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. The post-MRI classification showed that the highest proportion of vascular dementia cases was detected using the ADDTC criteria. The DSM-IV criteria ranked second, while the lowest proportion of patients was diagnosed using the NINDS-AIREN criteria. The diagnosis of vascular dementia by the DSM-IV and NINDS-AIREN criteria identified a group of participants with severe vascular disease. The ADDTC criteria identified participants in the border zone between Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia or patients with no history of strokes but with severe MRI-identified vascular disease. Of the 132 subjects with a pre-MRI diagnosis of vascular dementia (alone or mixed), only 38 (29%) were classified as vascular dementia by all three diagnostic criteria. None of the vascular dementia criteria were able to successfully identify all of the MRI-confirmed cases of vascular dementia. Interestingly, based on the composite scores of neuropsychological data available in 243 patients, it was found that patients with probable vascular dementia had poorer visuospatial and fine motor control performance than did those with a diagnosis of probable vascular dementia with Alzheimer’s disease, possible vascular dementia with probable Alzheimer’s disease and possible vascular dementia with possible Alzheimer’s disease. No other statistical differences among groups were noted on tasks of memory, language, or executive functioning. The strengths of this study included a standardized MRI protocol for the 480 subjects and extensive premorbid longitudinal clinical data that allowed the researchers to examine the relationship between dementia and vascular disease.