F rontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that commonly afflicts people in middle age, when they are in the prime of life.

1 Frontotemporal dementia is the most common manifestation of the frontotemporal lobar degenerations, a group of disorders characterized by degeneration of the frontal lobes, anterior temporal lobes, or both. Unlike patients with Alzheimer’s disease, patients with frontotemporal dementia present greater social and personality changes than with cognitive or neuropsychological deficits.

1 –

3 The most common presentation of frontotemporal dementia is an abulic, apathetic personality change with disengagement from usual activities.

3,

4 Frontotemporal dementia is often misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed.

5 –

7 The FTD Consensus Criteria and other neuropsychiatric criteria lack sufficient diagnostic accuracy for the clinical diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia early in its course.

1,

2,

7 For example, in one study the Consensus Criteria diagnosed only about one third of frontotemporal dementia patients at initial presentation.

7 Clinicians need sensitive measures of neuropsychiatric symptoms that can aid in the earliest diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia.

One hitherto undervalued sign of frontotemporal dementia is laziness of thinking or “Denkfaulheit.” “Mental laziness” is part of the apathy-abulia spectrum and may underlie many personality changes in this disorder. Early “Denkfaulheit” in frontotemporal dementia more accurately refers to an inappropriate cognitive shallowness with lack of depth, drive, and motivation.

8,

9 This preliminary study evaluates the presence of this symptom on a semistructured interview in well-characterized patients with frontotemporal dementia compared to those with Alzheimer’s disease and healthy comparison subjects.

METHOD

Subjects

All of the frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease participants were community-based patients who presented to Neurological Clinics of UCLA. The study excluded patients on medications, particularly antipsychotic drugs, or with medical, neurological, or psychiatric disorders that could otherwise account for their neuropsychiatric symptoms. The frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease patients had two scales reflective of dementia severity: the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR).

10,

11 The clinical diagnostic assessment included routine laboratory data, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, and functional brain imaging with either positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission tomography (SPECT).

Eleven frontotemporal dementia patients were recruited for this study. On initial interview, the physicians determined the presence of the diagnostic features of frontotemporal dementia on the FTD Inventory.

12 All frontotemporal dementia patients met Consensus Criteria for FTD, i.e., they met all the necessary core features of the Consensus Criteria for FTD in the absence of other neuropsychiatric illnesses.

1 The core features included an insidious onset and gradual progression, an early (within 2 years of onset) decline in social interpersonal conduct, an early impairment in the regulation of personal conduct, emotional blunting, and early loss of insight. The clinical diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia further required confirmation with the presence of frontally predominant changes on PET or SPECT. Finally, the patient had to be within 2 years of the first symptom onset.

The 11 patients with Alzheimer’s disease met established research criteria of clinically probable Alzheimer’s disease after completing a diagnostic evaluation.

13 For this study, the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease further required confirmation with the presence of temporoparietal-predominant changes on PET or SPECT. In order to match the frontotemporal dementia patients, an effort was made to select patients with Alzheimer’s disease who had an early age of onset and who were only mildly impaired.

Eleven individuals without a history of neurological or psychiatric disease participated in this study as an additional normal comparison group. The healthy comparison subjects were recruited primarily from spouses of patients.

Procedure

The study administered a semistructured interview divided into three parts. Part 1 consisted of five questions regarding preferences (e.g., If you had a choice, what would be your preferred hobby or pastime, job or profession, place to live, type of vacation, food to eat?). Scoring was based on whether they expressed preferences or denied them (e.g., “I do not know” or “that is all”). Part 2 consisted of five questions assessing depth of responses (e.g., What would you do if you lost all of your money, your car broke down on the freeway?). The subject was asked to describe the reasons for his or her behavior. Scoring was based on whether they gave a description consisting of multiple steps or limited to a single step. Part 3 assessed the readiness to say what the interviewer appeared to want to hear. It consisted of a paragraph followed by five questions: “A man took his girlfriend out to dinner. Afterward, she insisted on going to the movies. Consequently, he brought her home very late at night.” Immediately afterward, the subject was asked five questions: Did the man eat dinner alone? Did the girlfriend get what she wanted? Did they watch a good movie? Did the girl get home early enough? Do you think that the girl’s parents might be angry? After each answer, the subject was asked: “Are you absolutely sure?” Any change of answer was scored as a positive “shift” according to a suggestibility paradigm.

14RESULTS

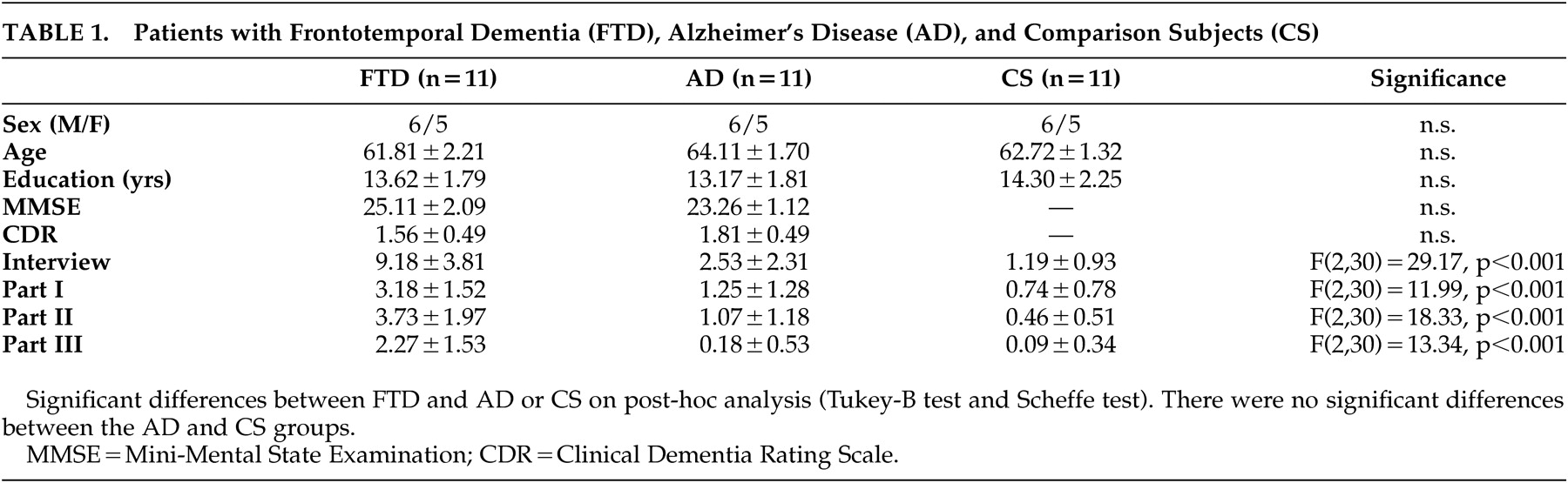

The three groups were comparable in gender, age, years of education, and dementia severity (

Table 1 ). Interrater reliability for two raters of the last four participants in each group (N=12) yielded a concordance rate for the interview items of 86.7% with kappa=0.688. Validity was reflected in the content of the three parts of the interview and in its correlations with items on the FTD Inventory.

12 The FTD Inventory item of apathy positively correlated with the interview scores (r

s =0.71, p<0.001), and the FTD Inventory item of hypomania-like behavior negatively correlated with the interview scores (r

s =−0.52, p<0.001).

The frontotemporal dementia patients were impaired on the “Denkfaulheit” inventory compared to the Alzheimer’s disease patients and the healthy comparison subjects. The frontotemporal dementia patients had significantly more “cognitive laziness” on the total score and all three individual parts (

Table 1 ). Post-hoc analyses showed significant group differences between the frontotemporal dementia patients and Alzheimer’s disease patients and between the frontotemporal dementia patients and the healthy comparison subjects but not between the Alzheimer’s disease patients and healthy comparison subjects.

Additional analysis of the frontotemporal dementia patients revealed several notable responses. A 56-year-old former construction worker with progressive aspontaneity and disinhibition had PET imaging consistent with bilateral frontal disease and frontotemporal dementia. On interview, he was asked how he had changed and he described himself as having become “shallow.” Another patient, a 59-year-old lawyer with a 2 year history of progressive disengagement and poor decision-making, also had bifrontal hypometabolism. When asked how he was different from his premorbid personality, he stated that “thinking was now as good as doing.”

DISCUSSION

These findings suggest that “Denkfaulheit” is more prominent in patients with early frontotemporal dementia in comparison to those with Alzheimer’s disease and healthy comparison subjects. The semistructured interview measures cognitive shallowness. This characteristic may be among the earliest manifestations of frontotemporal dementia.

Frontotemporal dementia can be difficult to diagnose early in its course. There is no definitive biomarker for this disorder, and the main manifestations are alterations in social and emotional behavior. One early sign, however, reflects the loss of motivation and depth of thinking. This mental laziness is manifested by shallowness of verbally expedient responses and may be a specific manifestation of apathy or abulia. “Denkfaulheit” may manifest as a lack of preferences, a shallowness of explanations, and an ease of suggestibility. Patients answer questions without thinking them over and may say what is expedient or give indecisive “Yes-No” answers.

“Denkfaulheit” is a manifestation of decreased behavioral initiation and spontaneity, loss of interest, and frank apathy in frontotemporal dementia.

15 Liu et al.

3 demonstrated that apathy and loss of dominance were characteristic of frontal involvement in frontotemporal dementia. Diehl-Schmid et al.

4 evaluated the prevalence and severity of behavioral disturbances in patients with frontotemporal dementia using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory and found that apathy was the most prevalent symptom in over 90% of the patients.

This study had several potential deficiencies. First, the number of subjects was relatively small. The subjects, however, were well-differentiated. Second, the interview is not an established, validated instrument. This preliminary study sought to evaluate the presence of this behavioral attribute rather than to establish a “Denkfaulheit” interview. Third, “Denkfaulheit” is not specific for frontotemporal dementia. Other patients with frontal lobe disorders can manifest cognitive shallowness, and clinicians need to use this sign in the context of other indices of frontotemporal dementia.

In conclusion, cognitive shallowness may be a potentially valuable characteristic for detecting frontotemporal dementia early in its course. When applied early, a semistructured interview for this symptom could help detect patients with frontotemporal dementia before the development of more prominent behavioral disturbances. This is a promising but preliminary study, and more research is needed on the utility of “Denkfaulheit” for frontotemporal dementia.