E arly descriptions of obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) in schizophrenia can be found in Bleuler’s

1 monograph on “dementia praecox.” Bleuler stated, “compulsive thinking (obsession) is the most common of all the automatic phenomena” and further described OCS in schizophrenia as “automatisms,” which are comparable to auditory or visual hallucinations in that they are “hallucinations of thinking, striving, and wanting” (p 450). Confirming these observations, case reports

2 and larger systematic studies have since suggested that more than a third of persons with schizophrenia experience clinically significant OCS,

3 –

5 while roughly 10% to 25% meet full diagnostic criteria for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

6 –

11 Emphasizing the significance of OCS in schizophrenia are a number of additional studies indicating that the presence of OCS in later phases of the illness is linked with poorer social and vocational function,

12 greater service utilization,

3 and lesser preferences for active coping strategies.

13 Taken together, one interpretation of these findings is that the co-occurrence of schizophrenia and OCS reflect the presence of both the structural and functional abnormalities associated with schizophrenia and OCD.

14 –

16 Accordingly, it has been suggested that individuals with schizophrenia and OCS/OCD may represent a group of persons with particularly grave cognitive and functional deficits.

17 Research supporting the latter hypothesis includes studies linking OCS with deficits in several domains of executive function, including abstract reasoning

18 and abstract flexibility.

19 –

21 However, others have failed to replicate these findings.

22While research to date represents a promising start, the literature on cognitive function and OCS in schizophrenia has been limited by at least three factors. First, nearly all pertinent studies have been cross-sectional and, thus, it is unclear whether assessments of executive function predict OCS prospectively. Second, OCS naturally involves heightened levels of anxiety. As anxiety is known to interfere with performance on neurocognitive tests, it is unclear whether links between OCS and neurocognition go beyond the general effects of anxiety. Third, executive function consists of multiple domains, not all of which are equally impaired in schizophrenia.

23 To address these limitations, we assessed OCS and general anxiety level concurrently and repeated these assessments 6 months later. We also chose three tests which tap into a unique domain of executive function, namely “inhibition,” which has been found to be uniquely linked with OCD.

24 We predicted that measures of inhibition would be linked with OCS at both the first and second time points, controlling for anxiety level at the time of each OCS assessment.

METHODS

Participants

Forty-one men with schizophrenia spectrum disorders were recruited from the outpatient service of a VA Medical Center or local community mental health center for a study of the prevalence of anxiety symptoms. All participants were in a stable or post-acute phase of their disorder, as defined by receiving outpatient treatment with no hospitalizations, changes in housing, or psychotropic medication within the last month. Diagnosis of schizophrenia (n=20) or schizoaffective disorder (n=21) was determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID),

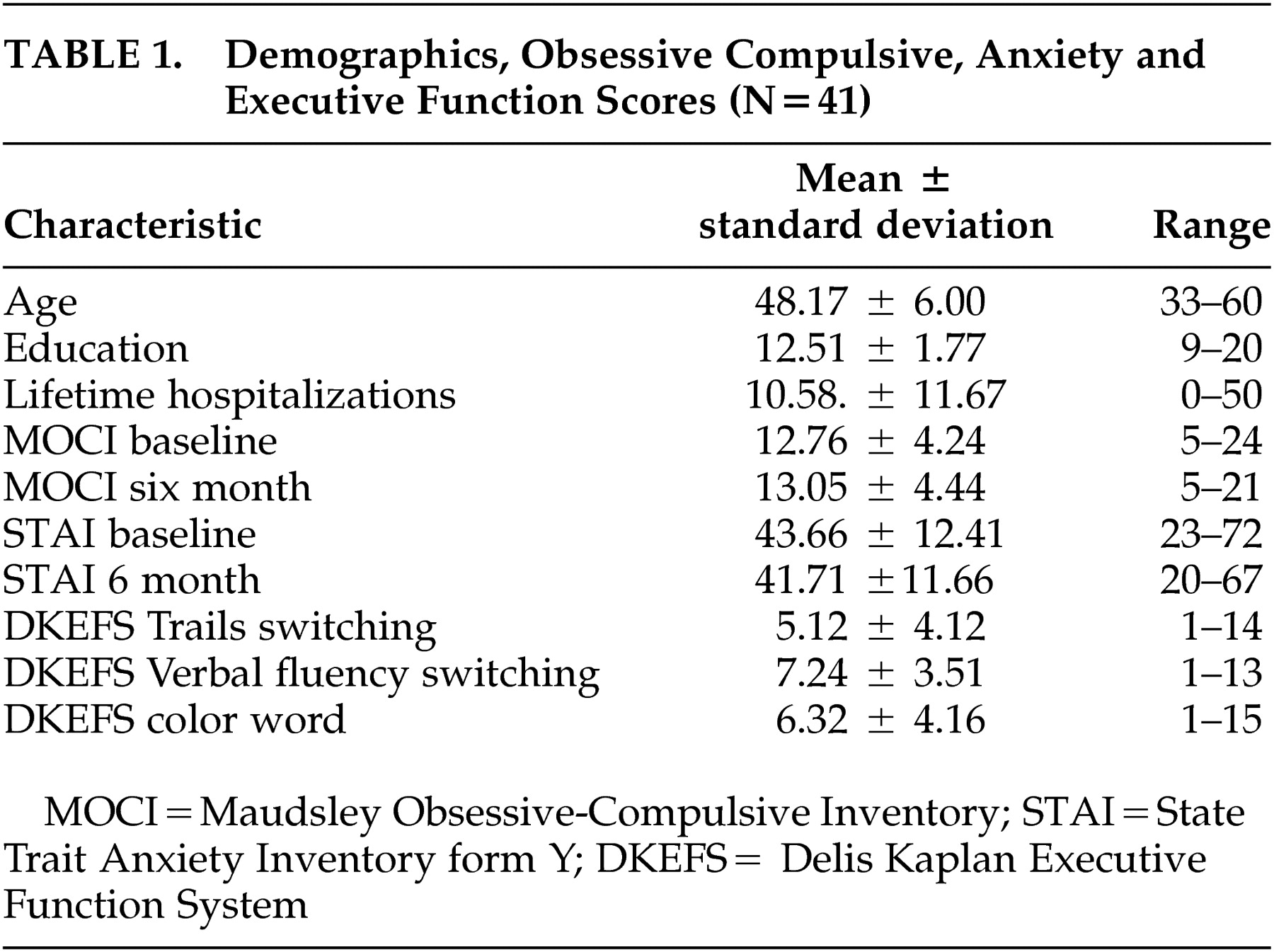

25 which was conducted by a clinical psychologist. Exclusion criteria for this study included evidence of mental retardation or active substance dependence in a participant’s chart or in interview. The participant demographics are summarized in

Table 1 . Twenty were Caucasian, 20 were African American, and one was Latino.

Instruments

The

Maudsley Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (MOCI)

26 is a 30-item questionnaire that asks participants to endorse statements which reflect checking and cleaning behavior, slowness, and doubting as true or false as applied to them. Higher scores reflect greater levels of OCS. Persons with OCD tend to achieve scores of 16 or higher.

27 Examples of items include: “I spend a lot of time every day checking things over and over” and “I do not usually count when doing a routine task.” This scale has been used successfully with a wide range of psychiatric and community populations.

26 –

28The State Trait Anxiety Inventory form Y (STAI)

29 is a 40-item questionnaire that asks participants to rate the extent to which they experience various manifestations of anxiety. Items are scored to produce two scores: state anxiety, or anxiety in the present moment, and trait anxiety, or anxiety that reflects an enduring proneness to anxiety. For the purposes of this study we were interested exclusively in state anxiety or current level of anxiety.

The Delis Kaplan Executive Function System

30 is a battery of traditional executive function tests revised to maximize demands placed on the ability to inhibit one response and choose another. In this study, we selected three scores linked to inhibition switching: Trails Switching addresses how quickly the participant can alternately connect numbers and letters on a printed page with a pencil; category-switching, taken from the verbal fluency task, assesses how many words from alternating categories can be produced verbally; and inhibition-switching, taken from the color-word task, evaluates the capacity to alternately name the color of the ink a word is printed in (which spells out a different color) and then read the word ignoring the color in which it is printed. We chose these tests because together they tap inhibition switching capacities using tasks that call for a range of visual, phonemic, and motor skills. Thus a general score generated from these is unlikely to reflect difficulties in one specific area.

Procedures

The appropriate research review committees of Indiana University and the Roudebush VA Medical Center approved all procedures. Following informed consent, diagnoses were determined using the SCID. A clinical psychologist (PL or LD) conducted all diagnostic interviews. Following the SCID, participants were administered the STAI, the MOCI, and the Delis Kaplan Executive Function System at baseline for a study of the prevalence of anxiety symptoms in schizophrenia. The MOCI and the STAI were assessed a second time 6 months later. Neurocognitive testing was conducted by trained research assistants with a minimum of a bachelor’s degree in psychology or a related field. Testers were blind to results of the MOCI and the STAI.

Analyses

Analyses were planned in three phases. First, as MOCI and STAI data were not likely to be normally distributed, we planned to normalize those scores and then correlate them with demographics. Second, to derive a score to estimate the inhibition component of executive function we planned to perform a principle components analysis followed by a varimax rotation in order to derive an overall factor score for each participant on the basis of the three Delis Kaplan Executive Function System subtests most closely identified with this dimension. Finally we planned to correlate the executive function factor score with both MOCI scores, covarying for state anxiety and other demographics related to either MOCI score.

RESULTS

Demographics and mean MOCI, STAI, and the Delis Kaplan Executive Function System subtest scores are presented in

Table 1 . Correlations of these scores with demographics revealed no links between MOCI scores and education or hospitalization history. Age was linked to the MOCI score at 6 months (r=0.38, p=0.03) but not baseline (r=0.06, p=0.77). Maudsley Inventory and STAI scores did not differ significantly between participants with schizophrenia as opposed to those with schizoaffective disorder.

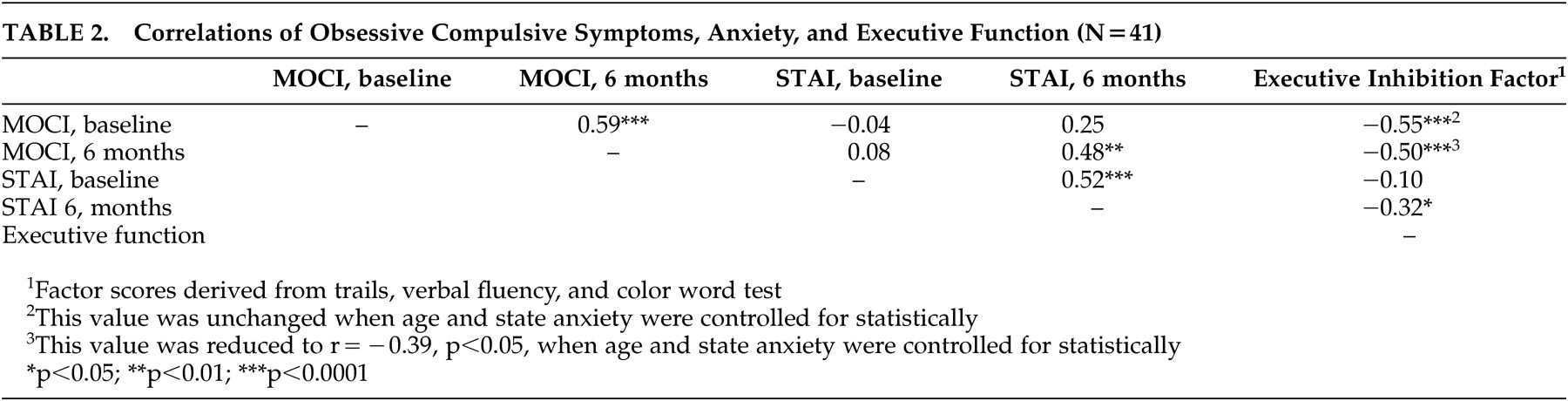

Next, a factor analysis which included a principal components analysis, followed by a varimax rotation, was performed using the Trails switching, category-switching on the verbal fluency task, and inhibition-switching from the color-word task of the Delis Kaplan Executive Function System. This produced one factor with an eigen value over 1 (1.64) which accounted for 55% of the total variance. Maudsley Inventory and STAI baseline and 6 month scores were then correlated with one another and with the factor score produced by these procedures. Baseline MOCI and STAI scores were closely linked with their respective 6 month scores (

Table 2 ). Maudsley Inventory at 6 months was significantly linked with STAI scores at 6 month, but not at baseline. The executive function inhibition factor score was significantly associated with the MOCI scores gathered concurrently and 6 months following. When age and state anxiety were controlled, the inhibition score remained significantly linked with both MOCI scores.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, assessments suggestive of lesser capacities to inhibit thoughts and behavior were linked with greater concurrent and prospective self-report of obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) among persons with schizophrenia. This finding persisted even when age and overall anxiety level were controlled, although these adjustments reduced the magnitude of the association between inhibition and OCS 6 months later. Results are thus consistent with the hypotheses that the presence of deficits in the inhibition domain of executive function in schizophrenia are linked with the presence of enduring OCS, regardless of the degree of anxiety that accompanies these symptoms.

While the presence of only two assessments of OCS and one assessment of inhibition limits the drawing of causal inferences, these results may generate and support hypotheses for future research. In particular these findings may be interpreted to suggest that OCS in schizophrenia may be a reflection of the presence of both forms of underlying pathophysiology associated with schizophrenia and OCD. Deficits in the inhibition domain of executive function have been widely observed in schizophrenia

21,

23 and, moreover, appear to be a particular point of dysfunction for persons with OCD who do not have schizophrenia.

24 Perhaps, as others

14 have suggested, the development of OCS in schizophrenia reflects the concurrence of the structural and functional abnormalities associated with schizophrenia and OCD. Importantly, rival hypotheses cannot be ruled out, including the possibility that biological or social factors not assessed were responsible for the associations observed here. Of note, the reduced degree of association between executive function and OCS found at 6 months when other variables were accounted for may suggest that the link between OCS and executive function is attenuated with time.

There are additional limitations to this study. Since participants were men, amenable to treatment and in their late 40s, generalizability is limited. Replication is needed with women, with men in earlier phases of illness, as well as with others who refuse treatment. OCS were assessed using only self-report among a medium-sized sample. Future studies with more detailed and distal longitudinal assessments and larger samples sizes are needed. There are also many other biological and social variables that may impact OCS. These should also be assessed before any firm conclusions are drawn about the association of OCS with neurocognition.

This study is consequently a beginning. With replication and clarification of these issues, future research may point to ways to enhance the treatment and rehabilitation of individuals with schizophrenia and OCS. Perhaps with pharmacological, psychosocial, and psychotherapeutic treatments that target the types of anxiety underlying OCS, persons with schizophrenia who are experiencing particularly grave impairments may be better assisted.