Kim and colleagues

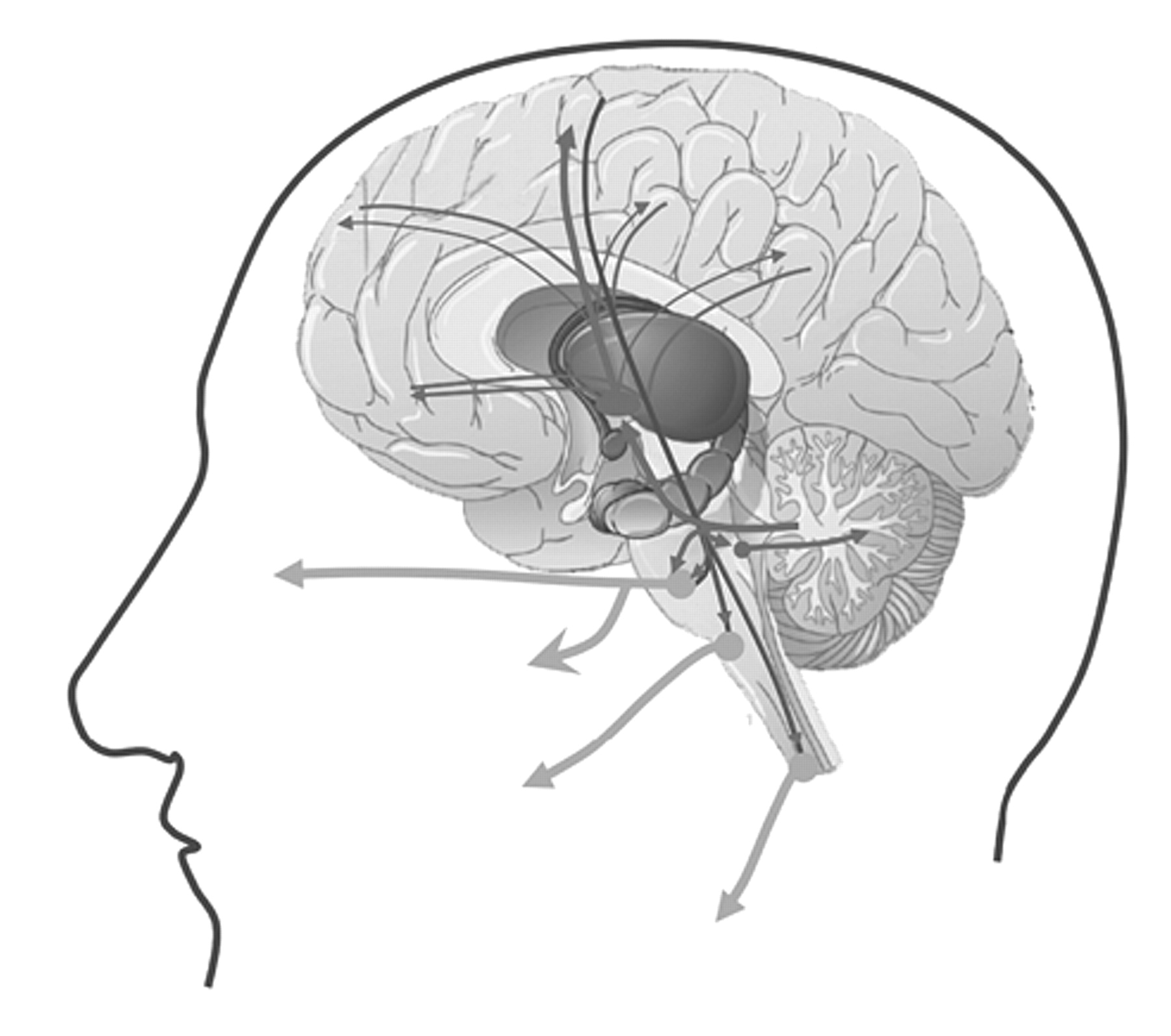

43 reported a prospective study of 148 patients who visited the outpatient clinic because of poststroke “behavioral symptoms.” Kim and colleagues asked the patients or their relatives if the patient had shown “excessive or inappropriate laughing.” If either the patient or the relative confirmed more than two occasions of excessive or inappropriate laughing, the authors scored them as having “emotional incontinence.” The location of the lesions was detected by CT or MRI. This study revealed that poststroke “emotional incontinence” occurred more frequently after stroke in the lenticulocapsular region, basis pontis, medulla oblongata, or the cerebellum. As noted earlier in studies of pathological laughing and crying, the definition of the problem often suffers from vague measures and that it is often defined significantly differently across different studies. For instance, in a similar study by House and colleagues

44 in 1989, the problem of “emotionalism” was defined based on three questions: have you been more tearful; does the crying come suddenly at times when you are not expecting it; if you feel that tears are coming on, and if they have started, can you control yourself to stop them? From their report, it is unclear how the authors distinguished significant from nonsignificant “emotionalism.” They studied the site of ischemic infarcts on head CT scans obtained from 128 patients with first-time stroke. They found “emotionalism” in 15% at 1 month, in 21% at 6 months, and in 11% of patients at 12 months. Patients with “emotionalism” had larger lesions and significantly higher scores on measures of mood disorders, psychiatric problems, and intellectual deterioration.

44 Andersen and colleagues,

45 in a short communication, reported “pathological crying” defined as a “condition in which episodes occur in response to minor stimuli without associated mood changes” in 12 patients with stroke. Of these patients, only four had isolated brainstem lesions whereas the others had brainstem

and large hemispheric lesions (n=4) or no brainstem lesion at all (n=4). One of the patients had an isolated cerebellar lesion. Among the four patients with isolated brainstem lesions, one had a large (>2 ml) lesion in the pons, another had a medium size (1–2 ml) lesion (location in the brainstem unclear), and the last two had only small (<1 ml) lesions (location in the brainstem unclear). Although the authors allude to a ventral location within the basis pontis, lesion locations in these patients lacked clear descriptions, making pathoanatomical correlations inconclusive. The authors nevertheless conclude that the lesions must have damaged the serotonergic nuclei in part because the patients responded to serotonergic therapy. Of note, the serotonergic system is not located in the ventral pons. Rather it is located posteriorly in the core of brainstem tegmentum, lesions of which are often associated with coma.

46 Kataoka and colleagues

47 studied 49 patients with acute paramedian pontine infarcts and classified them into paramedian, paramedian-tegmental, and tegmental. “Pseudobulbar affect with pathological laughing” (details of diagnosis unknown) was seen only in patients with paramedian basilar infarct, whereas none of the tegmental lesions caused pathological laughing. Arif and colleagues

48 reported a patient with a large paramedian basis pontis lesion who developed “pathological laughing” triggered by swallowing liquids but not solids. In keeping with these findings, Gavrilescu and Kase

49 reported that PLC is often associated with infarcts limited to the medial, rather than the lateral, territory of the basilar artery. Similar results were obtained by Kim and colleagues

13 who studied 37 patients with acute infarcts involving the base of the pons. They reported four cases with “transient uncontrollable laughter or excessive crying followed by inappropriate smiling,” and in all four, the lesion was in the paramedian basis pontis region. Paramedian pontine infarcts are particularly important because a single lesion in this territory causes

bilateral damage to neurons in the basis pontis and their projections to the cerebellum. Thus a single paramedian pontine lesion will cause bilateral and widespread compromise in the pontocerebellar system. Parvizi and colleagues

14 described the case of a patient with PLC (with a score of 20 on the Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale developed by Robinson et al.

15 ). This patient had cerebellar deficits in bedside testing and a significant impairment in aspects of executive functions as measured by the Tower of Hanoi task in formal neuropsychological testing. A high resolution MRI revealed five small lesions, the largest of which was 12 mm in diameter. These lesions affected the cerebellar white matter (three lesions) or the paramedian basis pontis (one lesion) where cerebrocerebellar pathways are relayed to the cerebellum. One small lesion (∼2 mm) was located in the left cerebral peduncle in its posteriolateral segment, at the site of descending tracts originating from the posterior quadrant of the brain to the brainstem. The patient was otherwise free of any other lesions in the frontoparietal or subcortical sites. Based on these observations, Parvizi and colleagues suggested that the problem of emotional dysregulation in their patient was due to the disruption of descending pathways from the brain (such as the frontal lobes) to the cerebellum through the basis pontis. Additional cases have confirmed the importance of basis pontis in PLC. Tei and Sakamoto

50 reported a case of a 69-year-old woman who presented with right hemiparesis accompanied by “pathological laughter” after an infarct in the basis pontis. Larner

51 described a case of “pathological crying” with basilar artery occlusion. Doorenbos and colleagues

52 reported a case of a 73-year-old right handed man with left basis pontis (and cerebellar) hemorrhage, who developed “forced involuntary laughter” whenever his left hand developed cerebellar intention tremor. For instance, each time he lifted his left arm, which then started shaking, the patient would exclaim “Oh, my!” or “here we go again” and would start laughing uncontrollably. Finally, Lauterbach and colleagues

53 reported a case of a 62-year-old woman with a small infarction in the thalamus who developed pathological laughter along with myoclonus, dysdiadochokinesia and dyscoordination, consistent with cerebellar outflow interruption.