Multiple scales have been used to assess depression in TBI patients, including the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D),

4 –

6 the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),

7 and the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies-Dementia scale (CES-D).

8 While these scales are useful to quantify severity of depression, the impact of a TBI extends beyond mood symptoms. Many studies have observed a detrimental effect of TBI on cognitive function

9,

10 and activities of daily living,

11 which can persist for many years following the injury.

12 The most common postconcussion symptoms are headaches, irritability, anxiety, dizziness, fatigue, and impaired concentration,

13 but a wider variety of symptoms that can include decreased libido, noise sensitivity, and social withdrawal have also been reported.

14 While it has recently been suggested that depression may increase the incidence of postconcussion symptoms,

15 little is known regarding the type of postconcussion symptoms experienced. A further exploration of the specific types and severities of postconcussion symptoms linked to the presence of depression would provide a better understanding of the impact of a mood disorder on TBI symptoms.

Factor analyses, using a variety of outcome scales, have been previously performed in TBI populations. A recent study looked at the factors of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies-Dementia scale in mild-to-moderate TBI and found that the items of this scale compacted into four factors, where mood accounted for two factors (depressed and positive affect) followed by daily tasks functioning (somatic/reduced activity) and social functioning (interpersonal relationships).

8 Another study in a predominantly mild TBI group without a prior diagnosis of depression, performed a factor analysis of the Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPCSQ)

16 and found that it formed three factors: cognitive, emotional, and somatic.

17Our goal was to determine whether patients with post-TBI depression report greater postconcussion symptoms and to characterize the type of postconcussion symptoms reported. We hypothesized that, following factor analysis to define relevant, population-specific postconcussion symptoms clusters, post-TBI subjects with depression would report greater mood impairment and other postconcussion symptoms compared to nondepressed patients. Gaining a better understanding of the differences between these two groups may highlight the effects of depression in the TBI rehabilitation process and provide a rationale for the treatment of depression in conjunction with postconcussion symptoms.

DISCUSSION

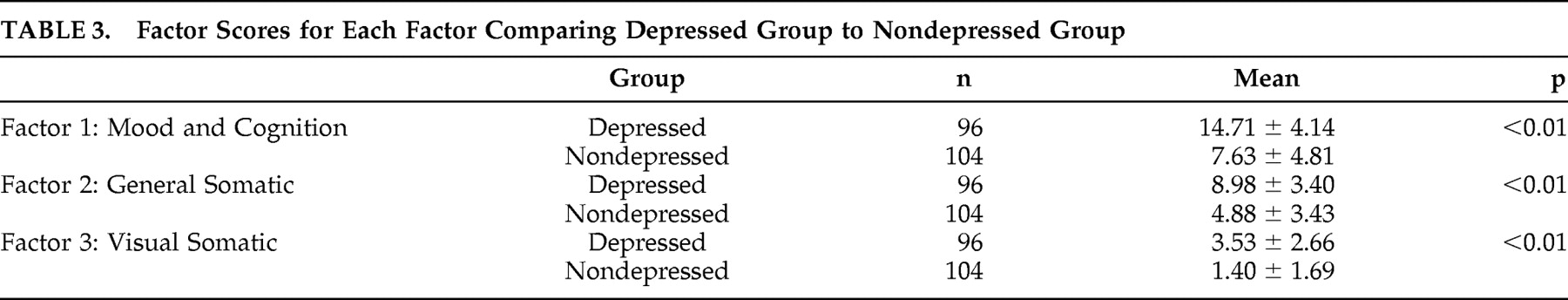

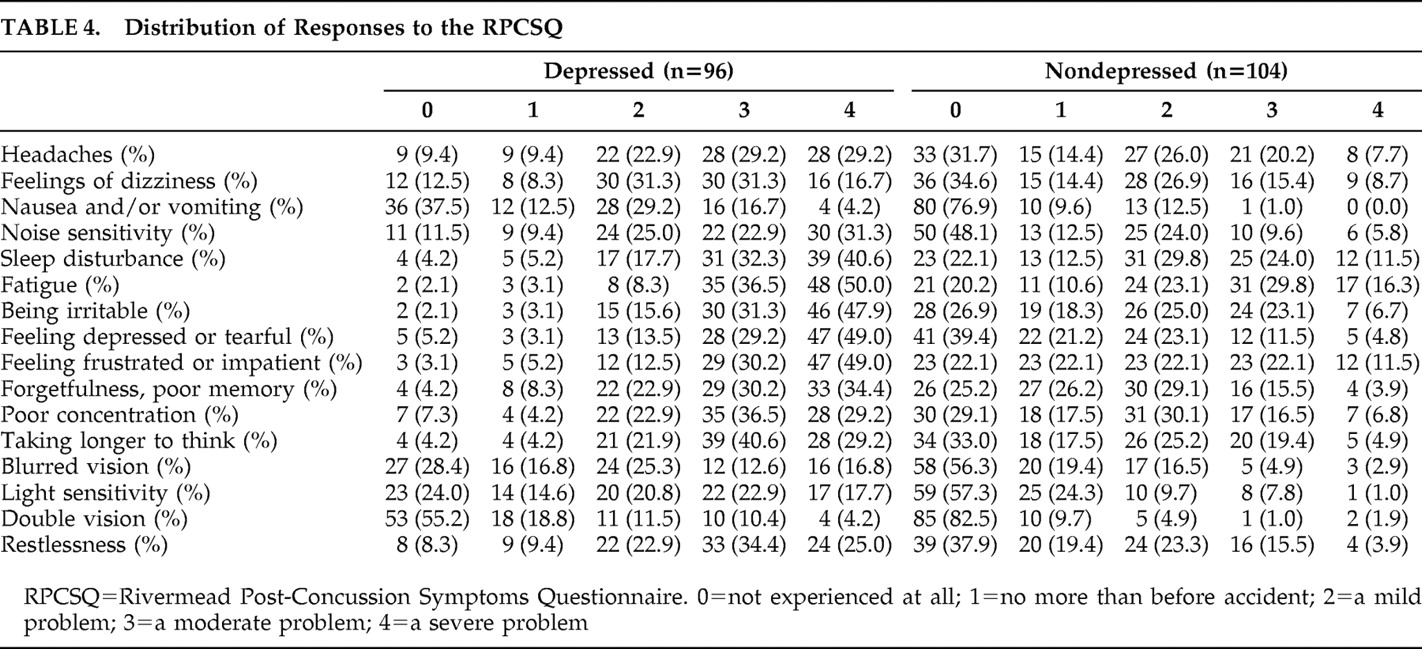

The main objective of this study was to determine if depression would influence how subjects reported an array of symptoms experienced post-TBI. The RPCSQ and the three distinct factors found in this study outline the impact of depression on the perception of postconcussion symptoms. We have found that depressed patients scored higher in all factor scores versus nondepressed patients. More interestingly, despite the high prevalence of somatic symptoms linked to mild-to-moderate TBI, somatic symptoms were still reported as more severe by those suffering from depression.

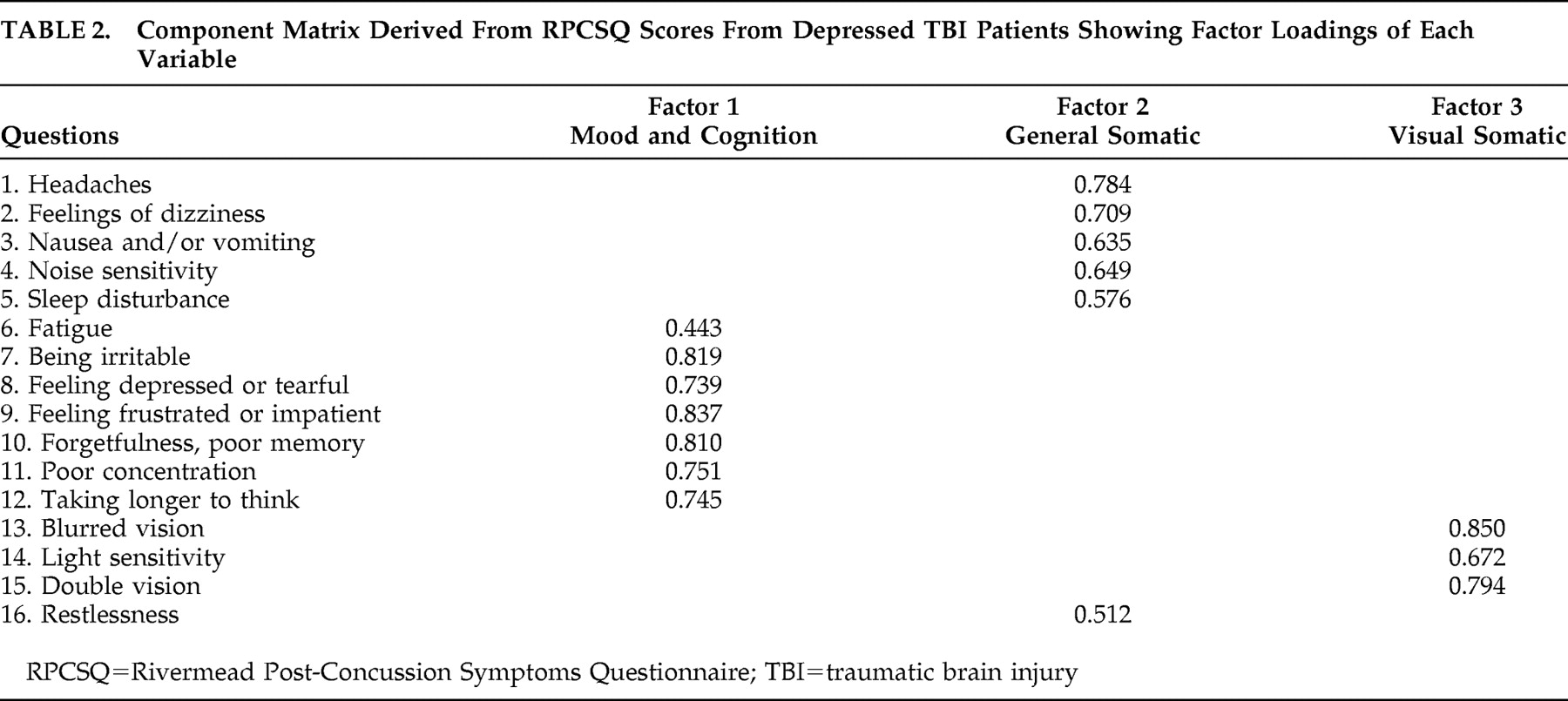

Factor analyses have been performed previously in TBI patients using a variety of validated scales. One such example is the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D), where four separate factors were found: depressed affect, positive affect, somatic/reduced activity, and interpersonal relationships. A factor analysis of the RPCSQ in a TBI population without a diagnosis of depression found that the 16 questions compacted best into three separate factors: somatic, emotional, and cognitive.

17 The results from our own study were similar to this study, in that we found three distinct factors. However, it must be noted that the individual variables were grouped into mood/cognitive, general somatic and visual somatic symptoms.

Regarding the mood/cognition factor, it is expected that individuals with depression, based on the SCID, would report more severe mood symptoms, which included irritability, feelings of depression or tearfulness, and feelings of frustration or impatience. The RPCSQ depressive symptoms subgroup thus confirms the results of the SCID. The cognitive factor group consisted of poor memory, poor concentration, and longer time to think. The depressed group reported higher impairment with these questions, which is consistent with previous studies: TBI patients with a diagnosis of depression have been observed to perform poorly on cognitive testing when compared to nondepressed patients.

2,

10 Somatic symptoms have generally been grouped together in previous factor analyses.

8,

20 However, we found that visual somatic, which dealt with blurred vision, light sensitivity, and double vision, formed its own factor that was separate from the general somatic symptoms. Visual impairment has been previously observed in patients with a moderate-to-severe TBI.

21,

22 A recent study found that individuals with a mild TBI were more likely to develop, among other illnesses, depression and visual imperceptions relative to healthy comparison subjects.

23 The visual somatic factor scores were significantly different between depressed and nondepressed patients in the present study, indicating that depressed patients reported more severe visual symptoms. Although the visual somatic symptoms experienced by our study group may be considered nominal, a study looking at postoperative cataract patients found an association between visual impairment and depressive symptoms.

24,

25General somatic symptoms, which included headaches, dizziness, nausea, noise sensitivity, sleep disturbance, fatigue, and restlessness formed the final factor. Common somatic symptoms observed in post-TBI include headaches, dizziness and nausea, which can occur immediately after the accident and persist for up to 6 months.

26 –

28 Comparing factor scores between the two groups, the depressed group reported greater somatic impairment. This could indicate that the presence of depression may be contributing to the severity of somatic symptoms, which is consistent with previous observations of depressed TBI patients when compared to nondepressed TBI patients.

29 Although RPCSQ scores have been previously compared between depressed and nondepressed TBI patients, this study goes one step further by examining the differences in specific symptom clusters in a larger subject group. The individual items of the RPCSQ were grouped into mood/behavior, general somatic, and visual somatic symptoms and scores were then compared on this basis. These findings suggest that depressed TBI patients report more severe postconcussion symptoms compared to their nondepressed counterparts. Since many postconcussion symptoms overlap with those of depression, depressed TBI patients may be experiencing a cumulative effect of head injury and depressive symptoms, therefore increasing the severity of symptoms reported by the depressed group. It has yet to be determined if this could influence the overall rehabilitation of this patient cohort. Another study found that the presence of secondary depression was associated with medical comorbidities, although this was observed in postmyocardial infarction patients.

30 With regard to the general depressed population, it was found that depressed individuals tend to report greater somatic symptoms.

31,

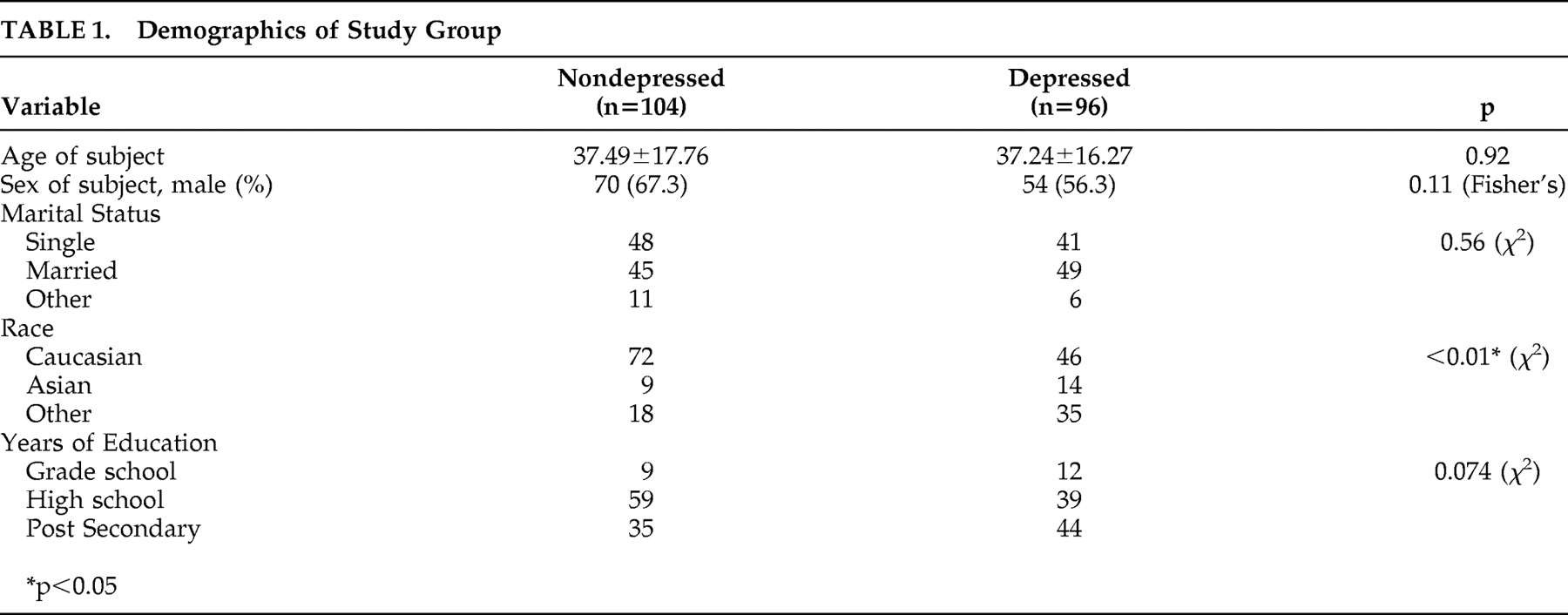

32Focusing on the demographic information of our study sample, race was significantly different between our study groups. It was found that a lower proportion of individuals who identified themselves as Caucasian were susceptible to developing depression compared to the Asian and other subgroups. However, self-reporting of postconcussion symptoms between depressed and nondepressed subjects was similarly greater in those with depression, irrespective of race. The number of years of education displayed a trend between the depressed and nondepressed groups, where individuals with a high school education or less were shown to be less likely to develop depression when compared to individuals with postsecondary education. A previous study has reported the opposite, showing that fewer years of education was a risk factor for the development of depression.

33 These factors may also be important in determining both depressive and other postconcussion symptoms.

Although our findings for this study highlight the differences between depressed and nondepressed TBI patients, some caution must be taken in interpreting our results. A potential limitation of the RPCSQ, a self-report scale, is that patients with depression typically report more severe postconcussion symptoms despite having similar severity of injury as nondepressed patients.

34 Utilizing a scale that would be administered by a trained interviewer or a physician may yield different results. Additionally, the validity of the RPCSQ as a scale has been recently questioned. A review found that the RPCSQ scale had good test-retest reliability and had the best construct reliability as two separate scales, where headache, dizziness, and nausea formed its own subscale.

35 Performing our factor analysis, we have essentially looked at the RPCSQ not as one score, but instead as a group of subscores pertaining to a specific symptom group. A second limitation of this study is the sample size. Although our sample group is 200 patients and is similar in size to other factor analyses,

17,

36 a larger sample size would be helpful to confirm these results. It is also important to consider that this study was performed in a regional trauma center, and the patient population may differ from a community population. A final limitation to this study is the diagnosis of a mild and moderate TBI. Within our own study, 55% of the study population met criteria for a moderate TBI while 45% were considered mild. To diagnose our study participants, we have used the guidelines put forth by The American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine. There is some controversy regarding the classification of TBI severity, particularly with the length of posttraumatic amnesia. While we characterized a moderate TBI as a posttraumatic amnesia of 1–7 days, other groups would consider this a severe TBI

37 or have alternatively opted to use only GCS scores.

38 Recently, a new guideline, the Mayo TBI Severity Classification System, considers a posttraumatic amnesia greater than 24 hours a characteristic of a moderate-severe TBI.

39 The variation in guideline use may lead to different conclusions when comparing TBI studies to one another.

40Despite these limitations, a strength of this study is that there was an objective diagnosis of depression using the well-validated SCID and this has allowed us to determine how depressed patients view their own somatic symptoms compared with nondepressed patients.

In summary, we found that depressed patients scored higher than nondepressed on self-reported mood, cognitive, somatic, and visual postconcussion symptoms. This study emphasizes the need to treat depression concurrently with rehabilitation, and suggests treatment response may improve postconcussion symptoms. This is consistent with other illnesses, where researchers have proposed treating patients for their depression in order to improve symptoms related to the primary illness.

41 By alleviating these depressive symptoms, TBI patients may more quickly regain their ability to lead an independent life style.