Investigators have studied acquired sociopathy or antisocial acts from acute, focal lesions but have not clarified the nature of sociopathy from dementia. Antisocial behavior has occurred from acute injury to the VMPFC and damage to adjacent regions, including strokes, trauma, infections, and ruptured anterior commissure aneurysms.

5,6 Less is known about the nature and etiology of a more insidious sociopathy from dementing illnesses with gradual onset and progressive course.

7,8 Yet, socio-moral disturbances can result from Alzheimer's disease (AD), vascular dementia (VaD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), Huntington's disease (HD), and other dementias. Some, but not all, of these dementias involve the VMPFC and adjacent frontal and anterior temporal regions, similar to those in acute sociopathic lesions. Others, however, may have different neuropathology and different mechanisms causing sociopathy.

Much can be learned from a comparison of sociopathy in dementia with acquired sociopathy from acute lesions and with the antisocial/psychopathic personality. First, most acquired sociopathy from acute frontal lesions appears to result from disinhibition, poor impulse control, and a tendency to react to immediate environmental stimuli.

9 Many dementia patients, however, have sociopathy that is not primarily due to disinhibition, but due to other mechanisms. Second, the sociopathy of dementia differs from antisocial/psychopathic personality disorder.

10,11 Dementia patients do not develop antisocial/psychopathic personality traits such as manipulation, deception, grandiosity, instrumental or goal-directed aggression, and calculated moral transgressions, but may have shallow emotions, lack of empathy, lack of remorse, a poor ability to learn from punishment, and reactive aggression.

9,12 Some investigators, however, report that lesions of VMPFC and adjacent areas, if acquired early in life, can impair the development of socio-moral knowledge and judgment, similar to the impairment of psychopathic personality.

13,14 Among patients with FTD, other investigators have shown decreased emotional responsiveness to others and a tendency to respond to moral dilemmas in a calculated fashion.

7,15,16These studies and others recommended further investigation of sociopathic behavior among dementia patients. Since sociopathy is distinctly recognized when patients get into trouble with the law, this study took legal action for sociopathic behavior as the inclusion criteria for sociopathy among dementia patients. Since impulsivity underlies most acquired sociopathy from focal frontal lesions, this study further divided these patients into impulsive versus nonimpulsive sociopathy groups. The purpose was to examine the frequency and nature of their sociopathic behavior and to contrast those with impulsive sociopathy, as in most acute-lesion patients, with others showing non-impulsive antisocial acts, as in many individuals with psychopathic traits.

RESULTS

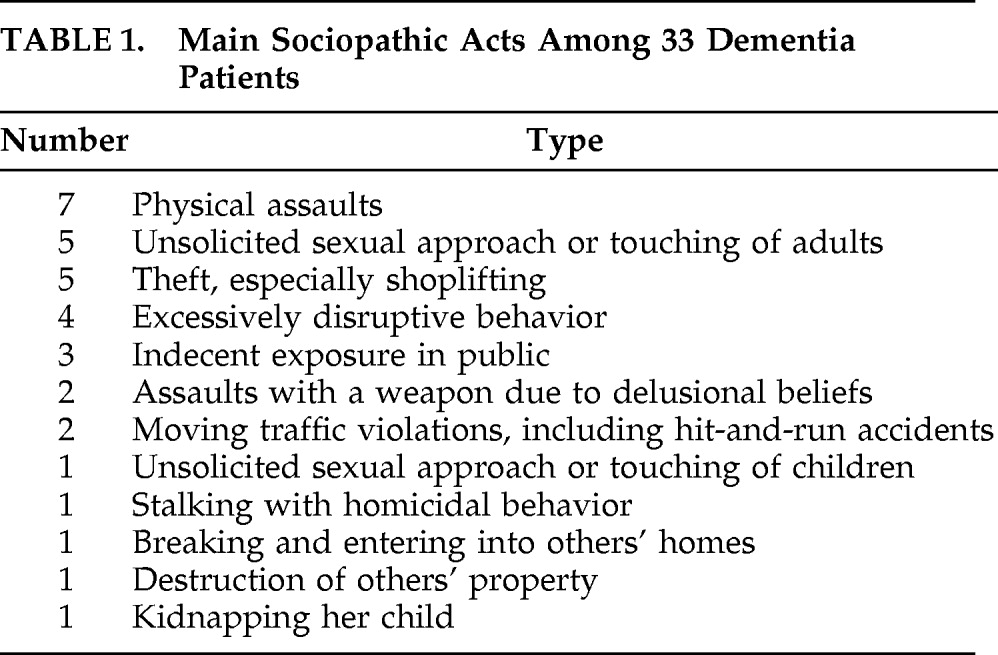

A total of 33 patients met diagnosis for dementia; met criteria for sociopathic behavior; and had sufficient clinical, cognitive, and behavioral characterization to be included in this study. Eight of these patients are further described in this section as vignettes labeled Patients #1–#8 (see below). The 33 patients had the following diagnoses: 8, Alzheimer's disease (AD; examples: Patients #1 and #2); 7, frontotemporal dementia (FTD; Patient #3); 5, vascular dementia (VaD) or anoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (Patient #4); 4, Huntington's disease (HD; Patient #5); 4, dementia with predominant aphasia (including 2 primary progressive aphasia and 2 multi-infarct aphasia, Patient #6); 2, Parkinson's disease (PD) with dementia; 1, autoimmune encephalopathy (Patient #7); 1, brain tumor (Patient #8), and 1, normal-pressure hydrocephalus (see

Table 1). The cerebrovascular patients with major aphasia were categorized as “predominant aphasia,” rather than VaD.

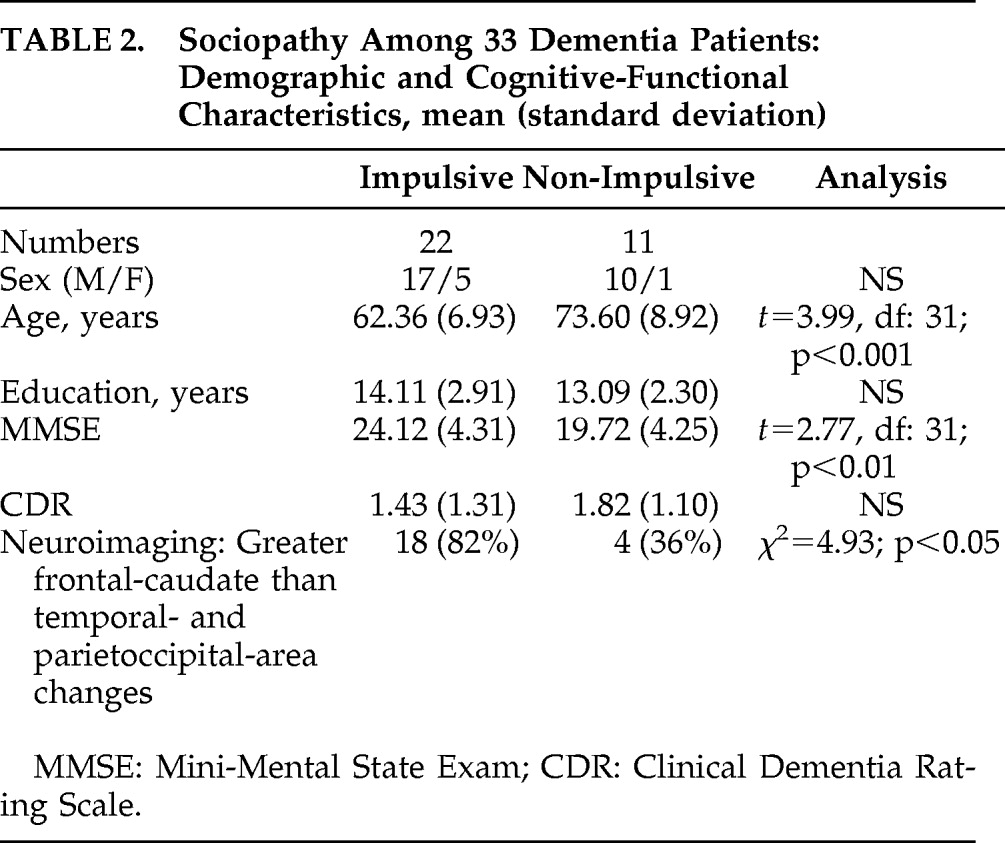

There were 22 patients in the Impulsive Group (including Patients #3, #4, #7, and #8) and 11 in the Non-Impulsive Group (including Patients #1, #2, #5, and #6). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups on sex ratio and education, but the impulsive patients were younger than the non-impulsive patients and less impaired on the MMSE scores (see

Table 2). The Impulsive Group had over twice as many members with greater frontal-caudate involvement (versus temporal and parieto-occipital areas) than the Non-Impulsive Group (χ

2=4.93; p<0.05).

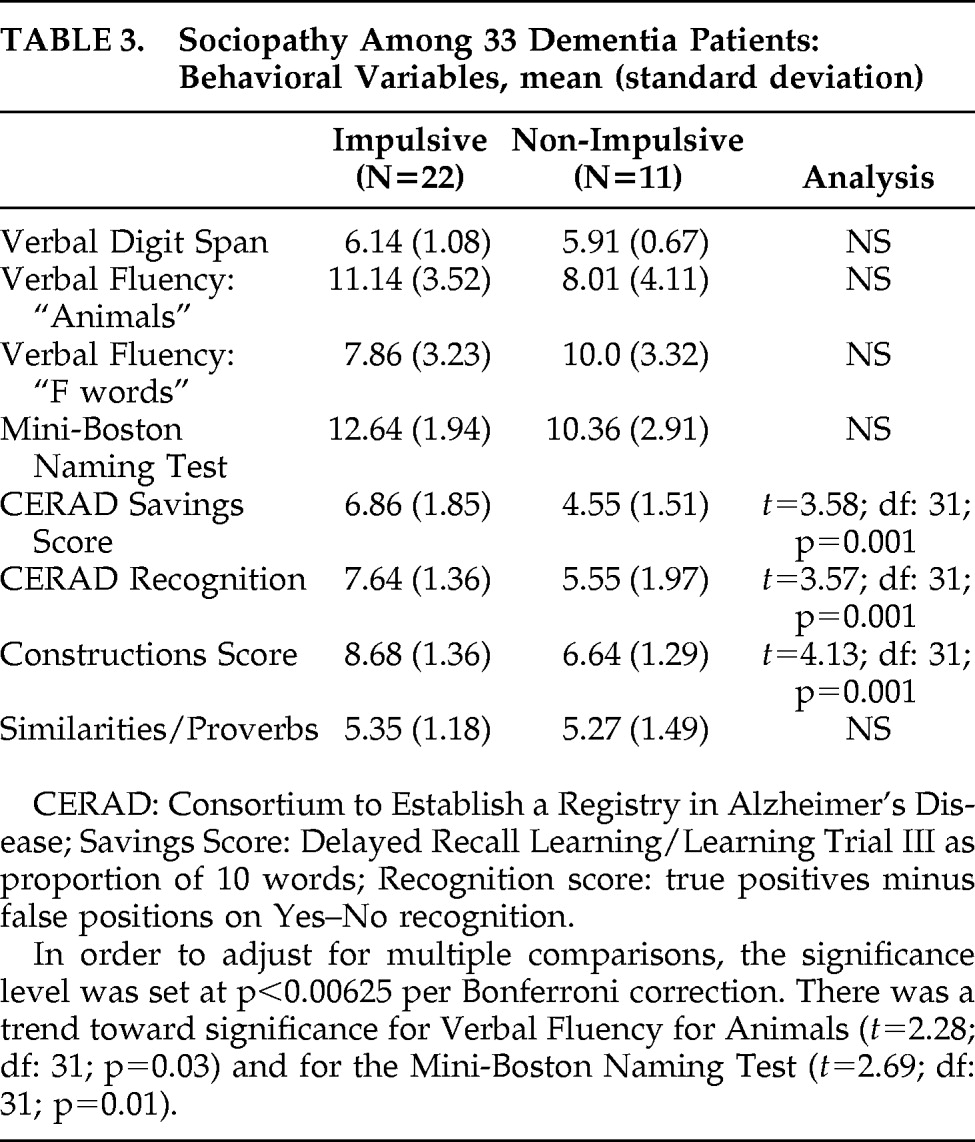

There were several differences between the Impulsive and Non-Impulsive Groups on the cognitive and NPI measures. Specifically, the Non-Impulsive Group was more impaired on memory items, both delayed recall, on the basis of Savings Score, and Recognition (see

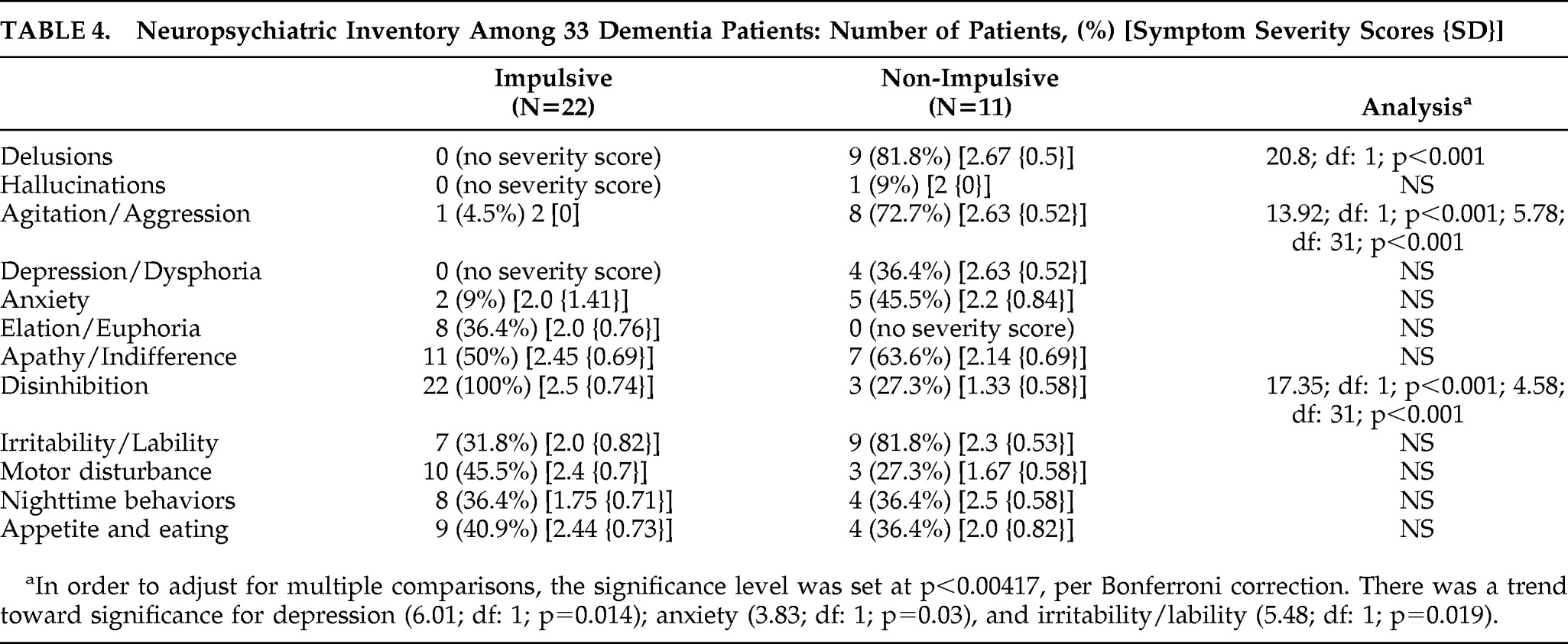

Table 3). Also, an analysis of their constructional ability showed significantly worse three-dimensional constructions among Non-Impulsive than Impulsive patients and a non-significant trend toward lower language scores. On the NPI, the Impulsive patients had predictably worse scores on impulsivity as reflected in the “Disinhibition” subscale (see

Table 4). In contrast, the Non-Impulsive patients had worse scores on delusions and agitation/aggression and a non-significant trend toward worse scores on depression, anxiety, and irritability/lability. What follows are eight examples of illustrative cases:

Patient #1

A 76-year-old man with a 5-year history of dementia was detained after he attempted to choke his hired caregiver. The patient had periods of agitation and aggression with minimal provocation, primarily directed at caregivers who attempted to assist him. When questioned about his actions, he expressed suspiciousness at their intentions. There were no other behaviors characterized as disinhibited or reflecting poor impulse-control. He had an extensive evaluation consistent with the diagnosis of AD. His examination showed an MMSE of 18 and marked memory impairment, with inability to recall any of 10 words after a brief delay. He had decreased verbal fluency and significant impairments on the mini-BNT in confrontational naming and verbal expression as well as on visuospatial constructions, including a clock-drawing task. His neurological examination was unremarkable, but MRI of the brain showed generalized atrophy, with disproportionate atrophic changes of the hippocampi on coronal views.

Patient #2

A 78-year-old man brandished weapons at others because he falsely believed that they were stealing from him. He had had a progressive decline in memory, other cognitive abilities, and instrumental activities of daily living, and was diagnosed with AD. More recently, he had developed the delusion that intruders were entering his house to steal from him. The patient repeatedly checked his belongings and his locks and doors and remained vigilant for strangers and intruders. While attempting to protect his belongings, he threatened to assault others with a bat, which resulted in legal action. He did not manifest impulsive behaviors. On mental status assessment, the patient had significant impairments in memory, with inability to recall any of 10 words at 15 minutes, and language, with inability to comprehend multi-step commands. The patient had additional deficits in visuospatial skills and executive abilities. His examination was otherwise normal, and his neuroimaging results were unremarkable.

Patient #3

A 57-year-old woman presented with an 18-month progressive personality change accompanied by petty theft. Whenever she was in a store, she would take things and walk out with them on the spur of the moment and without premeditation or concern for resulting legal action. She could describe her stealing in detail and endorsed that it was wrong but had become extremely disinhibited, with poor impulse-control. For example, she could not keep herself from approaching strangers and making personal comments. She had also developed compulsive behaviors, an addiction to ice cream, and decreased self-care. Family history was positive for early-onset dementia and motor-neuron disease. On examination, she had decreased confrontational naming, a memory-retrieval deficit, and decreased insight into her behavioral changes, but relatively preserved visuospatial skills. Her neurological examination and MRI of the brain were unremarkable, but SPECT imaging showed hypoperfusion in both anterior temporal lobes, more right than left. The patient was diagnosed with FTD.

Patient #4

An 80-year-old man sustained a hypoxic episode, resulting in cognitive and behavioral changes. He was in his usual state of health when he developed a cardiac arrhythmia and sustained anoxic encephalopathy as well as ischemic white-matter disease. On recovery, he continued to have multiple cognitive deficits. He also went from being a reserved person to being quite disinhibited. He displayed decreased impulse-control, with verbal outbursts and sexually inappropriate behavior. Whenever the opportunity arose, he would sexually grab and fondle both men and women, which resulted in several legal complaints against him. He was also disinhibited in his verbal comments and toileting behavior. Neurobehavioral and neurological evaluations revealed memory and frontal-executive deficits and frontal grasp reflexes. His MRI showed moderately-severe white-matter changes, and his PET scan showed hypometabolism more prominent in bilateral superior temporal gyrus and also in frontal regions. His cognitive and behavioral difficulties continued on follow-up over the next 2 years.

Patient #5

A 48-year-old man with a 3-year history of HD was served with a restraining order because of homicidal threats directed at his ex-wife. He stalked her, had violent outbursts directed at her, and threatened to kill her. He gave no explanation for his threatening behavior, and had little insight into his behavior, even denying having HD. In the past, he had also threatened to kill himself. His threatening behavior toward his ex-wife was not impulsive, but planned and premeditated. His family history included HD in one brother, his mother, and a maternal uncle. A genetic evaluation disclosed an allele with 47 cytosine–adenine–guanine (CAG) repeats (normal: 26 or fewer). His examination showed impairments in attention, memory, verbal fluency, and executive abilities. He showed facial grimacing and choreiform movements of his tongue and proximal upper extremities, with an abnormal gait. His CT scan of the head showed mild cortical atrophy, especially involving the caudate nuclei, and PET scan showed hypometabolism of the caudate and putamen bilaterally.

Patient #6

A 63-year-old man had Wernicke's aphasia as a result of strokes. He showed deteriorating behavior, with increased agitation and paranoia. On several occasions, he got into trouble for attempting to punch or choke family members or others. His wife reported that he had become suspicious of others, that his language made no sense, and that his comprehension was extremely impaired. His agitation and suspiciousness were ongoing, and his aggressive behavior predictable and not impulsive in the opportunistic sense. His medical history included coronary artery disease, with ventricular and atrial arrhythmias, angioplasty and stent placement, and pacemaker placement. On mental status evaluation, he was irritable and appeared paranoid. His speech was fluent but with paraphrasic errors and severe impairments in comprehension, repetition, and naming. Other cognitive deficits were evident in memory and visuospatial skills. His neurological and MRI examinations were consistent with multiple strokes, probably embolic, and a PET scan showed areas of hypometabolism including the left subfrontal region.

Patient #7

A 47-year-old man had a 2-year course of a subacute dementia. His problems began with a low-grade fever and drowsiness, followed by progressive personality changes and cognitive dysfunction, including memory and facial identification. He became disinhibited, with poor impulse-control over a background of apathy. He got into trouble for disruptive behavior in public. He would walk up to strangers, standing very close to them, and tell them about his sex life. He could not keep himself from making inappropriate comments or inappropriately touching others. His examination showed executive dysfunction, including frequent perseverations and stimulus-bound responses and anosmia. An MRI revealed bilateral mesiotemporal hyperintensities, but PET scans were normal. Electroencephalograms showed bifrontal slow waves. CSF and laboratory studies for paraneoplastic, infectious, or autoimmune causes were negative. He did not improve on intravenous steroid therapy and eventually died. Autopsy suggested an autoimmune limbic encephalitis.

Patient #8

A 56-year-old businessman was accused of taking money without delivering on his product. His wife noted an insidious and progressive change in his personality, with poor decision-making in his business and uncharacteristic sexual promiscuity, with many recent affairs. At one point, he was accused of indecent exposure. He was eventually hospitalized after an incident where, while waiting in a public line, he defecated in his pants but continued waiting as if nothing had happened. On admission, the patient was alert and attentive, but had decreased spontaneous verbal and motor behavior and poor impulse-control. Mental status assessment was consistent with impairments in memory, language, and executive functions. Although his neurological examination was unremarkable, multiple neuroimaging procedures revealed the presence of an infiltrating, low-grade “butterfly” glioma of the frontal lobes that crossed the corpus callosum. The tumor had spared the primary motor and sensory regions of the brain.

DISCUSSION

These patients illustrated the occurrence of sociopathy as a manifestation of dementia. This initial attempt at characterizing the nature and causes of sociopathic behavior among dementia patients showed that some patients committed sociopathic acts because of disinhibition, and others had sociopathic behavior associated with agitation-paranoia, rather than primarily from poor impulse-control. Only this later group manifested violence as a part of their behavior. The clinical evaluations further indicated that the Impulsive group had frontally predominant dementias, whereas the Non-Impulsive group was more cognitively impaired, particularly in memory and visuospatial constructions.

Dementia patients with sociopathy may be compared with “acquired sociopathy” from focal brain damage such as strokes and head injury.

22,23 Patients with acute lesions in the VMPFC and adjacent regions commit antisocial acts, have impaired moral judgment and empathy, and are emotionally shallow, with autonomic hyporesponsivity.

22,24–30 If the VMPFC lesions are acquired early in life, patients may have impaired development of moral decision-making.

13,14,31 When frontal lobe-injured patients commit antisocial acts, they are mostly disinhibited; that is, they are impulsively reactive to environmental stimuli, with decreased concern for the consequences of their behavior.

9,32 Also, damage to adjacent OFC regions of prefrontal cortex impairs automatic feedback from social cues, particularly angry or aversive expressions, and the control of impulsive responses.

9,13,23,33–37 In sum, frontally-impaired patients commit impulsive acts without emotion or concern for the consequences. Similar to these acute frontal-lesioned patients, many dementia patients with frontal-predominant disease commit disinhibited antisocial acts without premeditation or foresight.

Dementia patients with sociopathy may be further contrasted with patients who have antisocial/psychopathic personality.

10 Psychopathic personality traits include self-centered arrogance, callousness, the tendency to manipulate others, irresponsibility and dishonesty, sensation-seeking behavior, and instrumental or goal-directed aggression.

10,36 Psychopathic patients do not care about the consequences of moral dilemmas,

38–40 and they have reduced autonomic responses to the distress of others.

28,41,42 There is mounting evidence for an inherited propensity for psychopathic personality traits such as poor fear-conditioning and for frontotemporal changes on neuroimaging.

38,40,43–46 Moreover, psychopathic personality traits are correlated with decreased gray-matter volumes in frontopolar and orbitofrontal regions of the prefrontal cortex.

12,42,47–53 Among psychopathic patients, defective moral socialization occurs from early involvement of an extended frontotemporal network that includes deficits in orbitofrontal functions, such as impaired response-reversal learning, and in amygdalar functions, such as aversive or fear-conditioning.

12,40,47,50,53–58 Both dementia patients and acute frontal-lesioned patients differ markedly from psychopathic patients in the lack of early involvement of this extended frontotemporal network and the absence of personality traits such as grandiosity, deliberate deceitfulness, manipulativeness, instrumental aggression, or the constant craving for stimulation.

8,36,59The patients in this study indicate that, in dementia, sociopathic behavior results from at least two broad mechanisms: frontal disinhibition and agitation-paranoia. Dementia patients with frontal predominance often react impulsively to tempting environmental situations involving sexual or other objects of interest, without concern for the consequences. Sexual disinhibition in dementia may range from prolonged staring at someone to sexual assault and pedophilia, acts that are usually not aggressive or premeditated.

60 Pathological stealing in dementia resembles kleptomania, an impulse-control disorder resulting in stealing of unneeded items, but differs by an absence of increasing tension before the act and release of tension after the act. Sexual behavior, pathological stealing, and other disinhibited behaviors may occur in dementia syndromes with disproportionate frontal disturbance such as FTD, VaD, HD, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, and neurosyphilis. For example, sociopathic behavior occurs in more than half of patients with FTD.

7 These patients are aware of their behavior, know that it is wrong, but cannot prevent themselves from acting impulsively and are impaired on tests of motor inhibition.

7 Other contributing factors in FTD may include impairments in empathy, theory of mind, and the appreciation of moral transgressions and social concepts.

61–64Perhaps the commonest sociopathic acts in dementia are physical assaults. Among the patients in this study, physical assaults were correlated not with disinhibition but with paranoia-agitation, sometimes with misperceptions and sometimes with frank delusions. Patients with memory deficits or language deficits may severely misinterpret experiences or communications. This can lead to paranoia or suspiciousness and consequent reactive aggression. This can occur with the “paramnestic” delusions of AD, such as the delusions of theft or “phantom boarder,” and in the neuropsychiatric syndrome of Wernicke's aphasia.

65 Moreover, aggressive behavior is prominent among patients with bilateral lesions or atrophy of the amygdalae from temporal lobe epilepsy or encephalitic conditions.

66,67 This suggests that temporolimbic involvement with emotional, memory, or language-comprehension difficulty in association with poor frontal monitoring of their behavioral may facilitate paranoia-agitation and reactive aggression in dementia.

68There are potential limitations of this study. First, this is a retrospective investigation reliant on clinical testing. This methodology, however, allows an evaluation of significant numbers of dementia patients with sociopathy, with sufficient behavioral, cognitive, and neuroimaging information for characterization. Significant findings emerge when the patients are divided into Impulsive versus Non-Impulsive groups. Second, many dementia patients have disruptive behavior that is not necessarily termed sociopathic. In this study, the requirement for some form of “legal action” validates the “sociopathy” consequence of their behaviors. Finally, the MRI analysis is not quantitative because of the need to include different scans from different scanners. Nevertheless, this initial imaging data can provide a foundation for future work with more quantitative neuroimaging techniques. Moreover, using the clinical evaluations, it is clear that frontal-caudate involvement is more common in the Impulsive patients than in those in the Non-Impulsive group.

In conclusion, sociopathic acts among dementia patients occur for different reasons. Some result from behavioral disinhibition, especially among those with frontal involvement such as FTD, VaD, and HD. Others have paranoia-agitation with possible delusions, especially among those with temporal-limbic changes from AD. Much more work is needed in order to elucidate the nature of sociopathic behavior among patients with dementia. This study and the proposed classification are but a first step, but they should help define research directions in a prospective investigation. Also, the clarification of management choices for sociopathy in dementia is a critical area that requires further dedicated research.