“Ms A,” a respected and revered teacher in her 70s, had two successive admissions to a teaching hospital, after episodes of confusion and atypical behavior at home. She had no past history or family history of neuropsychiatric illness (e.g., bipolar disorder) and had a decade-long history of suffering with various cancers. While treated with tamoxifen for her breast cancer a few years earlier, she developed tubular cancer, and more recently was diagnosed with malignant mixed Mullerian adenosarcoma (MMMT; Stage 1C) for which she was treated with carboplatin and Paclitaxel chemotherapy (CarboTaxol regimen), followed by pelvic radiotherapy and brachytherapy. According to her husband and children, the neuropsychiatric symptoms leading to the admissions started abruptly, within 2 weeks of her second cycle of palliative chemotherapy with CarboTaxol. One evening, her husband found her trying to switch on the TV with the mobile phone. She appeared agitated when challenged about her behavior and insisted that “through her genial invention (sic),” she managed to re-wire their mobile so that it could be “multifunctional.”

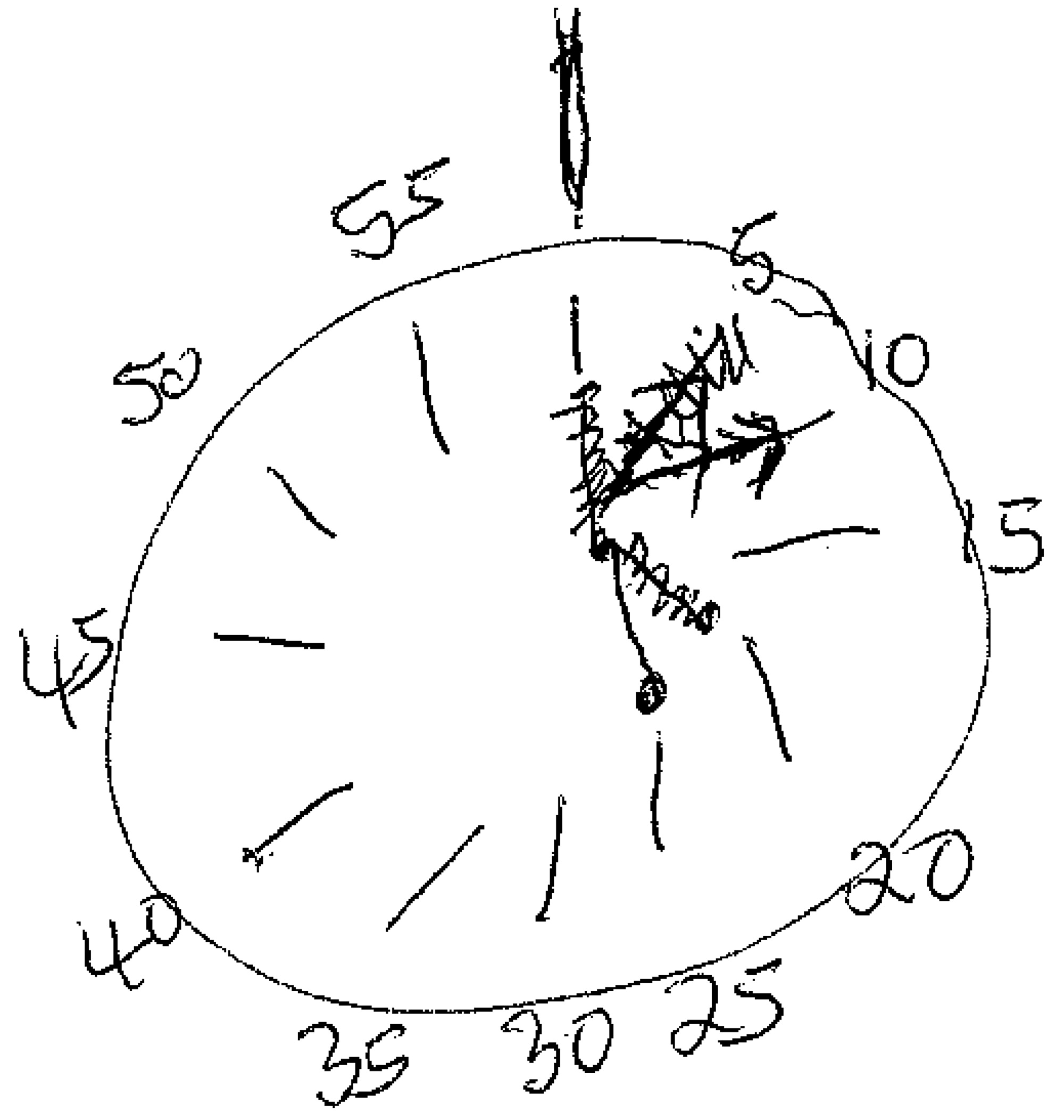

Similar outbursts of affective instability, pressured logorrhoea, tangential thinking, delusions, and irrational, grandiose, disinhibited and, at times, argumentative behavior were accompanied with progressive disturbance in her sleep cycle, personal hygiene, and eating during the next few weeks. The latter led to a dramatic drop in her BMI. Incidents of inappropriate toileting, disrobing, and extended naked periods were also reported. She gradually completely deferred from activities of daily living, and her husband had to take over most of the household duties. Her first admission followed the further abrupt decline in her mental state, with prominent confusion, “flight of ideas,” and loss of selectivity of mental processes. In the hospital, no unequivocal etiology of her delirium was found, and, after some improvement in her cognition, she was discharged home. Her family insisted that she continued acting out of character when at home, with prominent mixed affective instability, lingering predominantly in the hypomania/manic spectrum. Her premorbid prim demeanor, with ascetic and anankastic traits, was overwhelmingly replaced with flippant, jovial, inappropriate elements. She was reported to have contacted her young grandsons at school requesting them to do shopping errands for her. She also sent strange, “jargonistic” mobile phone messages. For example: “So xiting!!!…Ta for efforts. Must have gone away. Please forget about her.” (sic) More circumscribed microepisodes of psychosis and altered consciousness were also recounted. The second admission, during which our liaison psychiatric team was involved, followed similar escalation, some 6 weeks after the very first presentation. When in the hospital, she showed psychomotor agitation. She pulled out her intravenous cannula and started hitting, biting, and kicking the nursing staff while also trying to throw things out of the window. She was not responding to questions and kept rhythmically repeating “I blow my nose on M11, noo, nee, noo” (sic). Lorazepam 1 mg iv was given, with some success in calming her down. Mild hyponatremia was diagnosed and subsequently corrected. She was also empirically treated with antibiotics. CT and MRI scans of her head showed only normal involutional changes, with some small-vessel ischemia and no features to suggest parenchymal metastatic deposits. During examinations in ensuing days, she proved bemused, albeit an amicable and willing participant, with heightened affect. The nursing staff pointed to continuing fluctuating states, with prominent nocturnal excitement and grandiose, confabulatory, delusional, and hallucinatory elements present. Her speech was not dysphasic, but she showed marked logorrhea, with constant switches between topics. “Yes, these cards are from my friend.” (sic) Then, turning to the “get-well” cards on her night desk, she would continue addressing them: “Nice dress. This nurse reminded me, you need to collect my grandson from school. Today the party is later. It is soon Christmas, it will be fun.” (sic) Her behavioral lack of spontaneity was in marked contrast to her disinhibited speech, and she usually stayed in bed without any drive to initiate goal-directed actions. Overall, she showed very limited insight into her presentation. No suicidal ideation was ever present or reported. The diagnosis of manic delirium was made, and she was initiated on quetiapine 50 mg nocte, which, within 48 hours, reduced her affective and psychotic symptomatology and ameliorated her sleep architecture. Also, valproate 500 mg MR OD (Epilim Chrono) was started. Apart from this medication, she was only taking omeprazole, Movicol, senna, and Buscopan tablets. Her cognitive profile, a few weeks into admission, was relatively preserved, with frontal presentation; for example, resolution of conflicting tasks was somewhat impaired. She scored 29/30 on the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) and 80/100 on Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination (ACE-R), losing points on working memory, fluency, language, and visuospatial abilities (

Figure 1). The multidisciplinary team decision was made to postpone the subsequent cycles of the chemotherapy. One month later, on medication, no further psychotic symptomatology was noted, and the disinhibition, dysexecutive, affective, and cognitive elements of her mental state were all reported improved and stable.