Phylogenetically, the commissural fibers were present as a major group of extrinsic connections joining the hippocampi. In nonhuman primates, the dorsal commissure carries primarily presubicular and parahippocampal gyrus fibers to the contralateral entorhinal cortex. Gloor et al. in 1993,

1 proposed that, in humans, the spread though the dorsal hippocampal commissure is the only likely pathway of contralateral propagation for seizure discharges originating in mesial temporal structures with spread to the contralateral hippocampus. This pathway, according to them, is imperative in cases where the spread between mesial structures occurs before any involvement of the contralateral isocortex. Alternative routes were rejected as unlikely in light of the known primate anatomy of the commissural and other connections of the temporal lobe.

1 This was in the direct contradiction to an existing body of work, which consistently refuted presence of hippocampal connections in humans.

3–5 More recently, Lacruz et al., 2007,

6 using SPES, also showed that, albeit rare, contralateral functional connections between medial temporal cortex and contralateral medial temporal and entorhinal cortices do exist in humans, with recorded latencies between 20 and 40 msec.

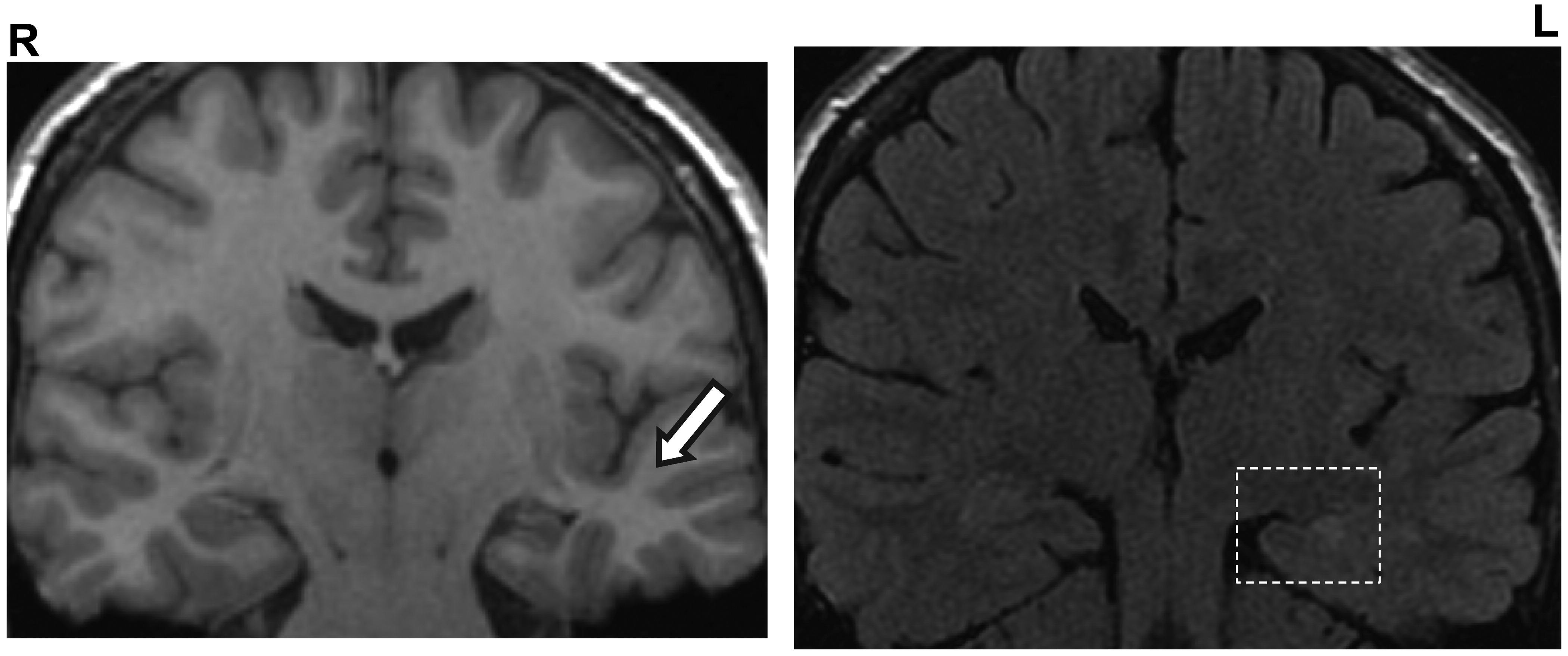

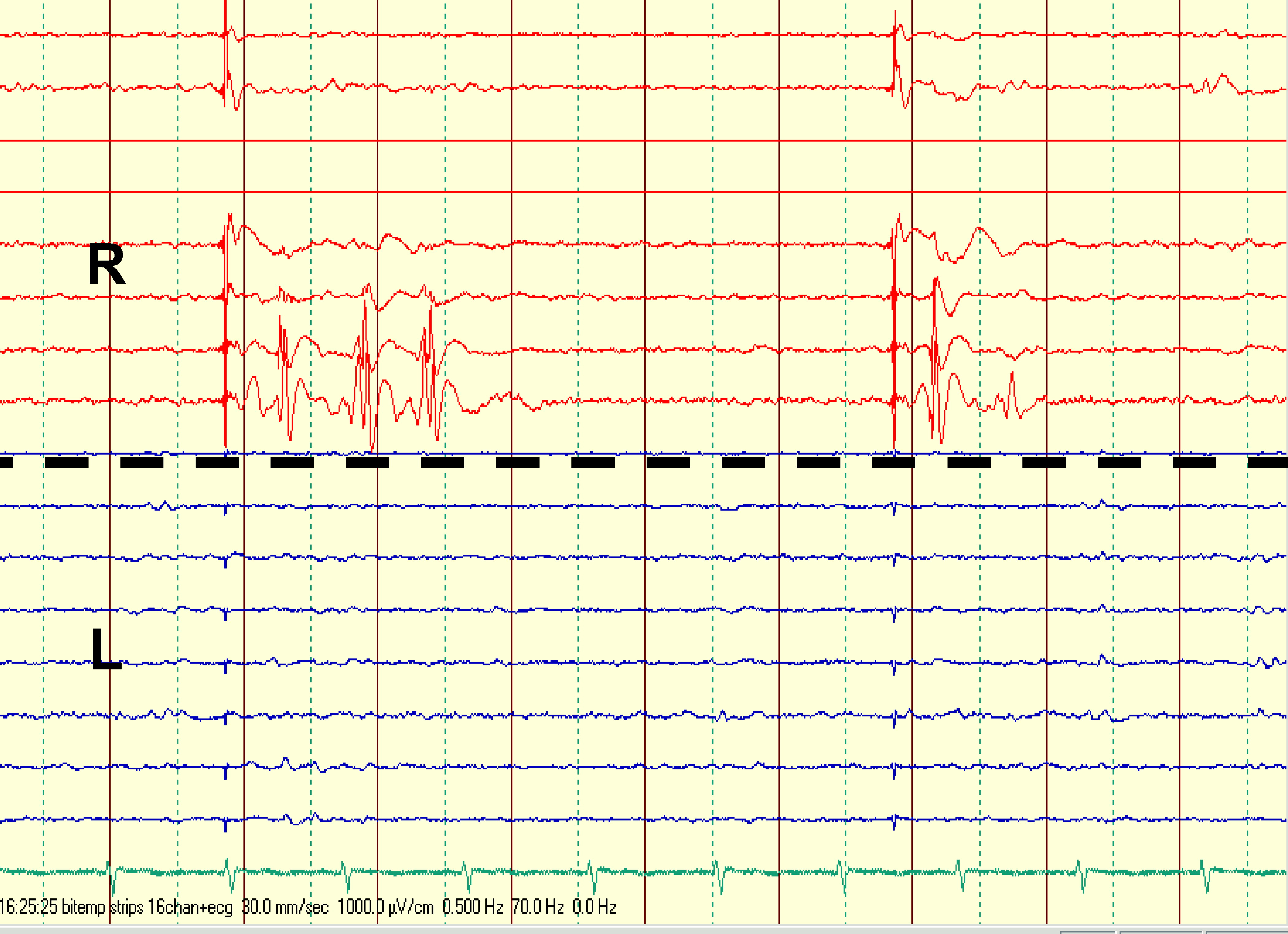

6 The presence of functional dorsal hippocampal commissure resonates in agreement with findings in our case and may indeed go some way toward explaining repeated false lateralization of seizure onset by extracranial and subdural EEG recordings in our patient. Presumably, only fortuitously placed intracortical depth electrodes could record seizure onset from such deep mesial temporal locus and “catch” it before its rapid (20 msec) switch via the commissure to the contralateral side. Furthermore, this commissural pattern of TLE seizure spread was suggested to be pertinent for the phenomena of pure amnestic seizures.

1 Pure amnestic seizures, or transient epileptic amnesia (TEA), sometimes occur in patients with TLE and commonly never represent the only type of seizures in these patients.

2,7 Here, the only clinical manifestation is the patients' inability to retain in memory what occurs during the seizure, coupled with the preservation of other cognitive functions and the ability to interact normally with their physical and social environment.

2 Interestingly, in our patient, one type of attack (i.e., “wandering episodes”) also arguably shared some of those features. It was postulated that TEA may result from selective ictal inactivation of mesial temporal structures without isocortical involvement.

2 Indeed, bilateral selective hippocampal inactivation was shown to induce memory deficits.

8 Theoretically, in patients such as Mrs A, whose memory function was supported by both hemispheres, TEA would need to be caused by seizure discharge limited to the MT structures of both temporal lobes; that is, requiring spread through the dorsal commissure. The reported duration of amnestic attacks in literature varies, but is generally accepted as anywhere between 30 and 60 minutes. A deficit in memory encoding or in storage mechanisms has been suggested as an underlying pathophysiological mechanism leading to the anterograde amnesia during the attack.

1 Olfactory hallucinations, automatisms, and other seizure types were all reported as additional features in some cases of TEA.

7 On the other hand, déjà vu, although associated with TLE and some other psychiatric and neurological conditions, is thought not to be common in TEA.

7,9 In this case, the additional presence of SPES abnormalities on the right, bilateral independent interictal EEG findings, and the evident “switching” of seizures further raised the possibility that the contralateral (right) temporal lobe could eventually become independently ictogenic, and a lower probability of a good postoperative seizure control achieved. Fortunately, in our case, the neurosurgery was performed promptly, and the patient rendered seizure-free. Of note is that although all seizure types remitted, the PNES endured. Moreover, the patient additionally developed agoraphobia. Panic disorder with agoraphobia, where the patient has an intense fear related to being in situations from which escape might be difficult or embarrassing, is the most frequently reported of the anxiety disorders in association with or following medical illness (e.g., gastroenteritis, cardiomyopathy, Parkinson's disease, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic pain, post-infarction heart failure, and primary biliary cirrhosis).

10 De-novo rise of psychopathology, especially that of depressive, anxious, or psychotic nature, following the epilepsy surgery is a well-recognized problem the exact nature of which merits further research.

11