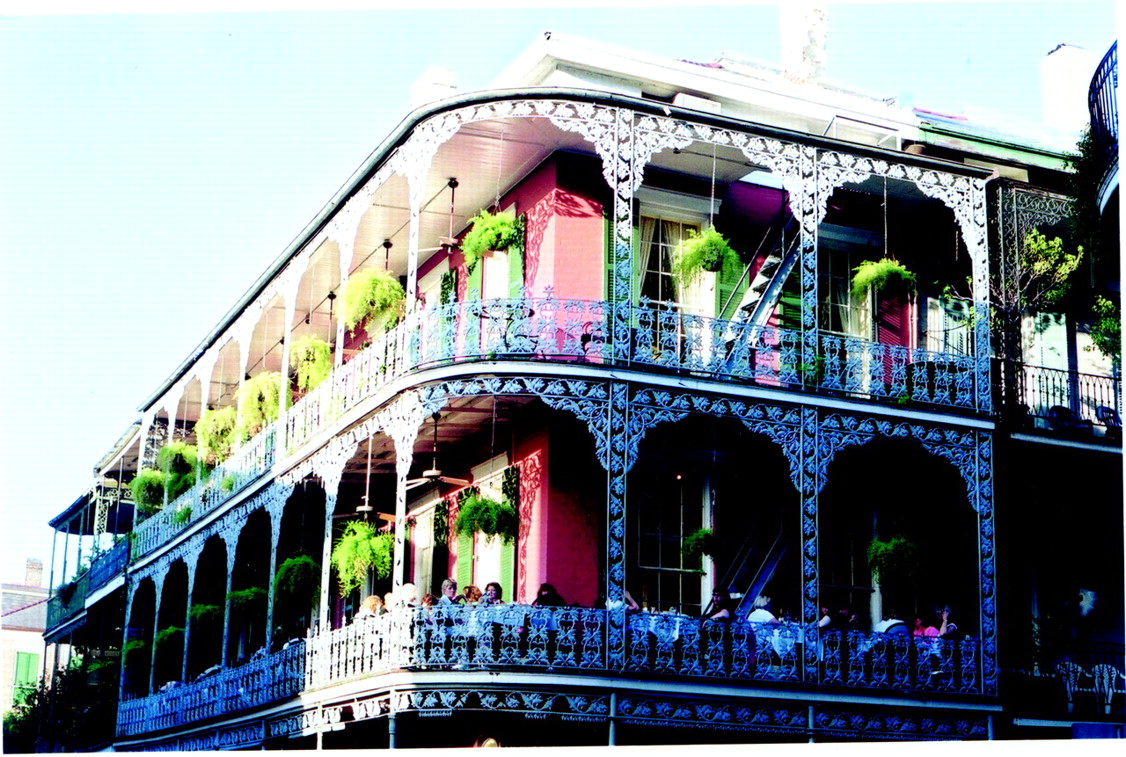

Whenever tourists visit certain parts of New Orleans’ French Quarter, they often think that they have died and gone to heaven. Luscious ferns and purple bougainvillea spill over wrought-iron balustrades. Fountains splash water in shadowy, inner courtyards. The air is soft, pregnant with the scent of gardenias and jasmine.

Yet only a few blocks up from the French Quarter—say, along Canal Street—the atmosphere is not so heavenly. In fact, it’s pretty down to earth. Here, it is clear that life can be tough at times, that people can have mental illness and not afford treatment.

Thus, enter Irma Bland, M.D. For people in this neighborhood and many throughout greater New Orleans, Bland is a savior of sorts. Indeed, she is CEO of public mental health in the greater New Orleans area, with more than 500 employees and an annual budget of $36 million to get help to such individuals.

How did Bland come to assume such an important position in the mental health world? It is a long story with many twists and turns, she explains in an articulate, thoughtful voice from her spacious office at 136 South Roman Street.

It may well have started back in the 1950s, when she was a little girl in New Orleans. One Christmas, her mother gave her older brother a doctor’s kit and her a nurse’s kit. That didn’t sit well with little Irma—second born but first girl! She chuckles.

In any event, by the time she entered Dillard University in New Orleans in 1966, she intended to become a medical technologist. But a West Indian professor there took a look at her high school credentials and exclaimed, as Bland recalled, “No, no, no, you will be doctor!” His brashness was not unusual for Dillard teachers, Bland says with a faint smile, “because Dillard was a historically black, Methodist university, and the culture was such that teachers saw your potential, encouraged you, and pushed you beyond your own expectations.”

So Bland pursued a premedical education at Dillard. She then went to medical school at the University of Chicago and eventually had to decide on a specialty. She considered gastroenterology, but soon realized that she was more interested in GI patients’ emotional health than in their physical health. When all was said and done, she decided on psychiatry because, as she says, “I liked the idea of being involved with patients in a way that you get to know them, to understand them, and the work you do with them makes such a substantial impact on what they are able to do with their lives.”

After finishing medical school at the University of Chicago in 1974, she did a psychiatry residency there, followed by a fellowship in adolescent psychiatry at Northwestern University in Chicago, and then went on to train as a psychoanalyst at the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis.

Bland worked at Northwestern from 1978 to 1987, first as an adolescent psychiatrist, then later as an associate director of residency training and coordinator of diagnostic assessment and psychotherapy training in its outpatient clinics. Then around 1987 she says her trajectory changed dramatically. “I had left New Orleans as a young woman on my way to medical school in Chicago with no intentions of ever returning,” she admitted. “But as life would have it, events culminated in my coming home.”

Louisiana State University School of Medicine in New Orleans had recently acquired a new chair of psychiatry, Howard Osofsky, M.D., Ph.D. Both the department chair and the medical school dean wanted to find a psychiatrist with a psychoanalytic background to teach their psychiatry residents and run the outpatient clinics. They recruited Bland, and she accepted.

Bland taught psychoanalytic psychotherapy to residents and ran psychodynamically oriented clinics there from 1987 to 1995. During these years she also interfaced considerably with the community and her administrative skills evolved as well, not only in terms of directing the outpatient clinics, but also when she became the associate chair for clinical affairs in LSU’s psychiatry department.

In 1995 the assistant secretary of Louisiana’s Office of Mental Health approached Bland about becoming the medical director of the office’s Metropolitan New Orleans area. She accepted and, while filling this position, continued to work part time teaching psychiatry residents at LSU. In June 2000 she was promoted to regional administrator/CEO for Region One of the Louisiana Office of Mental Health.

Making Lemonade From Lemons

It has been a year or so since Bland became head of Region One—one of the nine public mental health regions in Louisiana. What are her responsibilities? Running New Orleans’ acute care hospital units for adults, New Orleans’ adolescent hospital, and New Orleans’ community mental health centers.

“Although there are associate administrators or chief operating officers for the day-to-day operations at the hospitals and clinics,” she explains, “it is my responsibility to provide direction for them and to be involved in strategic planning, development, and implementation. I also oversee a regional pharmacy that provides medications for all of our patients. So basically, I have to provide executive direction and oversight and work with my regional medical director, with my operating officers at the facilities, and with my regional pharmacist.”

And what are the facilities that she heads up like? Since one picture is worth a thousand words, and since Bland is obviously a woman of physical action as well as of intellectual oversight and planning, she springs from her executive chair, escorts her visitor to the garage under her office building, and drives to, first, the acute care hospital and, second, one of the community mental health centers in her domain. At the two facilities she chats with various staff members who obviously know her well and think highly of her.

As Bland drives her visitor away from the facilities, she talks about some of the challenges facing her in her position. For instance: “Last year we went through a major budget cut, which meant that we had to cut not just hospital beds, but staff positions,” she says. “The situation was very hard on our staff psychologically. Not only were staff members who lost their jobs affected in very real ways, but it left remaining staff members with fewer resources to work with, they had to shift their frame of reference, and so forth. So what we did was restabilize the organization psychologically during this major downsizing, but we also attempted to create something positive out of a bad situation. And this was to compensate for the downsizing of hospital beds by building a more comprehensive continuum of care than we had had before. For instance, at our adolescent hospital, we reduced the number of beds. But we built, at the same time, a respite program on the front end that would divert kids from having to be in the hospital in the first place, that is, to stabilize them in crises, and on the back end we built a transition program to move kids out of the hospital quicker, yet to have them continue in treatment in an outpatient day treatment program so that they would have a little more time to stabilize.”

Another challenge, she explained as she heads her car toward the French Quarter, “is that funding is never predictable. And sometimes it leaves me in a crisis mode because the public mental health system is still the safety net. We are dealing with people who have serious, persistent, and chronic mental illness, with children who have severe behavioral and emotional disorders. We are dealing with the sickest of the mental health population, and their needs are continuing to increase, yet the money to provide care for them is not increasing and is even being slashed.

“But what I dislike most of all,” she confides as she drives past St. Louis Cathedral, “is that so much of it is out of my control. I mean, you have your little part of the world where you can exert some influence, but sometimes the decisions come from on high, from the legislature, and you have to carry them out, even though they may not be the most rational decisions or make sense in terms of resources. Yes, I think all public health care is in a vulnerable position, but especially public mental health care.”

Offers Hope for Recovery

But even with such frustrations and with her inability to bestow mental health on all of New Orleans’ citizens, Bland loves her job most days, she admits as she halts her car before the hotel on Royal Street where her visitor is staying.

What does she love most? “I love the fact that everything we do provides an opportunity for someone to recover from an illness that robs him or her of a sense of self-identity,” she said. “I love seeing patients recover from very challenging circumstances, knowing that we are making a difference in their lives. I love serving the traditionally underserved—ethnic minorities—and bringing my knowledge and skill to bear on their mental health problems. I love getting people to work together as a team and to watch them grow professionally. I love bringing together all of the things that have been a part of my education and my training. In some ways it feels like social activism. I am, after all, a child of the 1960s generation.”

So who is Bland in her deepest heart of hearts, who is that fairy godmother who waves a wand over public psychiatry in New Orleans, not just at Mardi Gras time, but throughout the year, and who makes it work?

One can ask Jackie Foster, Bland’s “right hand” for eight years now. As she told Psychiatric News. “I call her phenomenal! She really is. She likes to get the job done, and she does what she has to do to get it done. She gets everybody involved and makes sure that things are running smoothly.”

Or one can ask Patrice Ambrose, M.D., a young psychiatrist who first worked under Bland during her residency and who now works in one of Bland’s mental health clinics. “She is very caring, very committed to what she does,” she said. “And I am privileged to be working for her!” ▪