The unusually pointed advertising campaigns undertaken recently by a few of America’s pharmaceutical giants that make antipsychotic medications have been characterized as an all-out war. Indeed, one psychiatrist was recently quoted by a national publication as saying that “it’s as if a couple of children were squabbling over whose toys are better.”

Marketing salvos launched not only at physicians but also at national and trade press, including Psychiatric News, have narrowed their focus to differences in the side-effect profiles of the drug makers’ products. The flavor of the current campaigns has been unusual, however, with certain companies suggesting that their competitors’ drugs make people fat, clog their arteries, or lead to diabetes or fatal heart problems.

Underneath the current marketing war, launched late last year by Eli Lilly and Company and intensified by rival Pfizer Pharmaceuticals during APA’s 2001 annual meeting in New Orleans, lie subtle but quite significant differences in the pharmaceutical agents in the “atypical antipsychotic” class of medications.

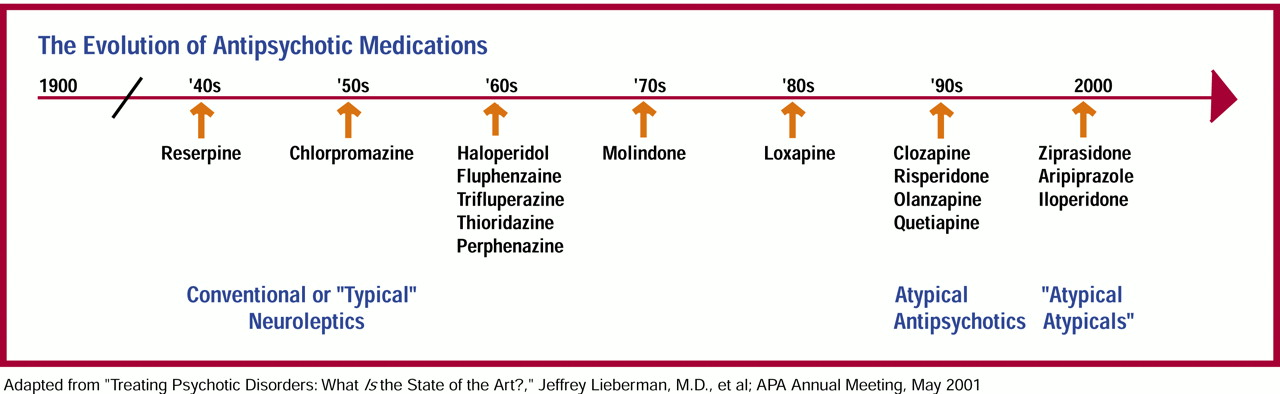

Now, with at least two new antipsychotics in the late stages of development (see box), one of which is being referred to as the first of the “atypical atypicals,” the physicians’ choice of which medication to prescribe for a growing list of indications, including schizophrenia, the psychosis associated with dementia, and in some cases acute mania and refractory depression, will undoubtedly become only more complex.

Marketing War

As the battle for market share has intensified, the pharmaceutical companies’ medical directors have been striving to keep the focus on the benefits their medications can bring to the many lives potentially destroyed by severe psychiatric illness, while candidly acknowledging and discussing the potentially serious side effects of the drugs.

“I cannot remember a time where I think an issue has been as potentially distorted with regard to risk as currently,” Steven Romano, M.D., senior medical director and team leader for ziprasidone at Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, told Psychiatric News. “Even being in the industry, it’s very frustrating to me because [the advertising] has caused a lot of confusion on the clinicians’ part.”

The war waged by marketing teams over Pfizer’s ziprasidone, sold in the U.S. under the trade name Geodon, and Eli Lilly and Company’s olanzapine, available as market leader Zyprexa, has become uncharacteristically intense for these two historically conservative companies. However, the market competition is tight and plays an important part in these two companies’ financial health (

see box on page 18).

Lilly has been running a print advertisement since late last year (including in Psychiatric News beginning with the December 1, 2000, issue) warning psychiatrists of the potential for certain medications, including some antipsychotics, to alter the heart’s QTc interval and therefore, in theory, increase a patient’s risk of potentially fatal abnormal heart rhythms. The Lilly ads have never included any reference to its own drug, not even as a potentially better alternative to competitors’ antipsychotics that may prolong the QTc interval.

The ad, however, does prominently feature a list of drugs pulled from the market, as well as those recently relegated by the FDA to second-line therapy and those required to have black-box and bolded warnings. Initially, ziprasidone was not included in that list, but when the FDA approved Pfizer’s Geodon in February, Lilly quickly added it to the top of the list in its ad.

At APA’s annual meeting in May, Pfizer fired back, releasing a study stating that olanzapine not only causes significant weight gain, but also significantly increases total cholesterol levels and insulin levels, putting patients, Pfizer said in a press release, at risk for both cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

To complicate the Lilly-Pfizer competition, Janssen Pharmaceutica—maker of the number-two antipsychotic on the market, risperidone (Risperdal)—began running print ads (first appearing in the February 16 issue of Psychiatric News) warning physicians about the incidence of documented hyperglycemia and type-2 diabetes mellitus with the use of atypical antispychotics. Although the ad mentions no specific medications, it does say that “certain atypicals are associated with a markedly greater volume of these reports than are others,” which some see as a veiled reference to olanzapine.

Efficacy, Tolerability Equals Success

The “antipsychotic war,” most psychiatrists say, should really be about what is best for the patient, and the company medical directors for the products in question agree.

“I would say that at the end of the day,” said Alan Brier, M.D., research fellow and leader of the Zyprexa product team at Lilly Research Laboratories, “patients and their doctors will speak with their prescription pads.”

Brier told Psychiatric News that what really counts is whether the patient is taking the drug, tolerating the drug well enough to continue taking it, and remaining stable on the drug.

The complex question of efficacy, safety, and tolerability is referred to as a drug’s “effectiveness.” Jeffrey Lieberman, M.D., the Thad and Alice Eure distinguished professor of psychiatry, pharmacology, and radiology and vice chair for research and scientific affairs at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, is directing the National Institute of Mental Health’s CATIE study, which is charged specifically with determining the effectiveness of the various antipsychotic medications (Psychiatric News, May 18).

Grouped together because their primary pharmacologic activity generally involves 5HT2A (serotonergic) and D2 (dopaminergic) receptors, the five atypical antipsychotic medications now licensed in the United States have mechanisms of action that, though still not completely understood, apparently differ markedly.

“These medications,” Lieberman, a corresponding member of APA’s Committee on Research on Psychiatric Treatments, told Psychiatric News, “allow significant changes and improvements in patients’ lives, as well as the lives of their families. But they are not all equal; they are each pharmacologically unique, and therefore each has slightly different mechanisms of action, efficacy, side effects, and tolerability issues. But there are no data yet to really say that one is ‘better’ than the other—we simply don’t know that yet.” The CATIE study should help to answer that question.

Teasing out the Data

Marketing hoopla aside, what really is known about the effects, both desired and adverse, of these medications?

“We should be encouraging all psychiatrists,” Ira D. Glick, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine, told Psychiatric News, “to take the high road and rely on the data.”

Glick is in a good position to argue the data, having used most of the drugs in question over the years, both in clinical research and in his large schizophrenia-centered practice. He also recently completed a meta-analysis of the efficacy and side effects of the atypical antipsychotics compared with the typical antipsychotic medications.

“John M. Davis, M.D., and I did the meta-analysis,” Glick told Psychiatric News, “as a response to the Geddes paper in BMJ [British Medical Journal].” They presented the meta-analysis at several poster sessions, including a session at APA’s annual meeting, and are preparing it for publication.

The article they were responding to, titled “Atypical Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: Systematic Overview and Meta-Regression Analysis,” by John Geddes, M.D., senior clinical research fellow at the University of Oxford department of psychiatry, appeared in the December 2, 2000, issue of BMJ. Geddes and his colleagues determined that there was no clear evidence that atypical antipsychotics are more effective or are better tolerated than conventional antipsychotics. The Geddes paper garnered a significant number of responses to BMJ, with most disagreeing with both the paper’s methods and its conclusions.

“Everyone read that analysis and the feeling was sort of, OK, your analysis of the data may say that,” Glick said, “but we felt that we were seeing something different in our clinical practice.”

Their meta-analysis, which has not yet been published, determined that “risperidone and olanzapine demonstrated a substantial, clinically meaningful, greater improvement compared with haloperidol.” The other atypicals studied—sertindole, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole—showed efficacy similar to haloperidol—probably because there haven’t been enough studies done, said Glick. On the side-effect profiles and the question of tolerability, he said that the atypicals, again, came out better than the conventional antipsychotics.

“My experience, in both clinical trials and in practice,” Glick said, “has been that the side-effect profiles of the atypicals are better; patients don’t feel as cognitively impaired, they’re not getting [extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia], so they are complying better and relapsing less. The quality of the patient’s life is a little bit better and so too is their family’s.”

Data comparing atypical antipsychotics with each other in head-to-head studies are, to date, limited. Lieberman’s CATIE study will be the largest real-world comparison, but data and conclusions are years away.

Serious Safety Concerns

Of the head-to-head studies to date, the most controversial so far is the study released at APA’s 2001 annual meeting, which was sponsored by Pfizer with Glick as lead investigator.

In that study, Glick compared ziprasidone with olanzapine on efficacy and the effects of the two drugs on weight gain and cholesterol, triglyceride, and insulin levels. Ziprasidone faired better in each category, causing less weight gain and showing little or no effect on the metabolic indicators, while olanzapine was linked to significant increases in serum total cholesterol and serum insulin levels.

Lilly’s Brier disputes the findings of the study and told Psychiatric News that the company is working on its own head-to-head comparison.

“Now, olanzapine has weight gain as a side effect, that’s a fact,” Brier said. But, he explained, significant weight gain is seen in about 30 percent of the patients. “It’s very important to understand that the majority of patients [experience] little or no effect on weight with olanzapine.”

In regard to the claims that olanzapine may put patients at risk of developing cardiovascular disease and diabetes, Brier called that “fuzzy advertising.”

“You’re talking about disease processes that take decades to develop—we simply don’t have those data yet,” he said in an interview. In a three-year review of prescription records of some 6 million people conducted by Lilly, the risk of developing diabetes was estimated for the general patient population and patients taking haloperidol, thioridazine, clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine. Ziprasidone could not be included because it was not available in the U.S. until this year.

The study found that the incidence of diabetes was comparable among patients taking either conventional or atypical antipsychotics. In fact, the risk with olanzapine was moderate, with the lowest incidence being seen with quetiapine and the highest with thioridazine.

For its part, Pfizer’s Romano said that Lilly’s inclusion of ziprasidone at the top of its QTc danger list in current advertising is unfair.

“It does not help physicians clarify the safety issue,” Romano told Psychiatric News. “It just scares them, and I think that is an important issue.”

In fact, a great deal of data is available on the QTc prolongation effects of the antipsychotic drugs. In general, studies have shown ziprasidone to have a substantial effect on QTc, second only to that of thioridazine, while olanzapine’s effect on QTc is comparable to placebo.

“There’s no question, ziprasidone has an observable measured effect on the QTc interval,” Romano said. “The question that remains is, What clinically meaningful effect, if any, is there due to that prolongation?” So far, data show no signal of a problem, he said. However, the database is still small, with somewhere around 50,000 prescriptions having been written for ziprasidone so far.

Both Lilly’s Brier and Pfizer’s Romano agree with researchers and clinicians like Lieberman and Glick that more data are needed to get clinically significant answers. In addition, research is ongoing to find ways to block, or avoid altogether, the antipsychotics’ observed side effects, and both companies are supporting that research.

Increasing Patient Options

William Carson, M.D., director of clinical research for aripiprazole at Bristol-Myers Squibb, isn’t shying away from introducing its new antipsychotic into such a hotly contested market (

see box) and believes there are very important reasons not to.

“There are larger questions about how you enter such a tight, or some people might say saturated, market. And I think the important thing that you have to remember is that there is still a very, very high unmet medical need in the treatment of schizophrenia.”

Lieberman agreed. Patients in general, he told Psychiatric News, are somewhat dissatisfied with their treatment options for various reasons—some for efficacy reasons, some for safety and tolerability reasons. Regardless of the reason, patients are very interested, he said, in new options.

“I think the sort of punchline to all of this,” Glick said, “is that you have existing drugs that are each good in its own way, but they all have issues of safety and tolerability—but it’s been difficult to see the long-term clinical significance of some of those issues.” When it comes to the bottom line, Glick said, “there simply are no miracles in the treatment of schizophrenia. Increasing the available options increases each patient’s ability to find the drug, or combination of drugs, which works best for them.”

The study “Atypical Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: Systematic Overview and Meta-Regression Analysis” can be accessed on the Web at www.bmj.com by searching under “Geddes” and the keyword “antipsychotics.” ▪