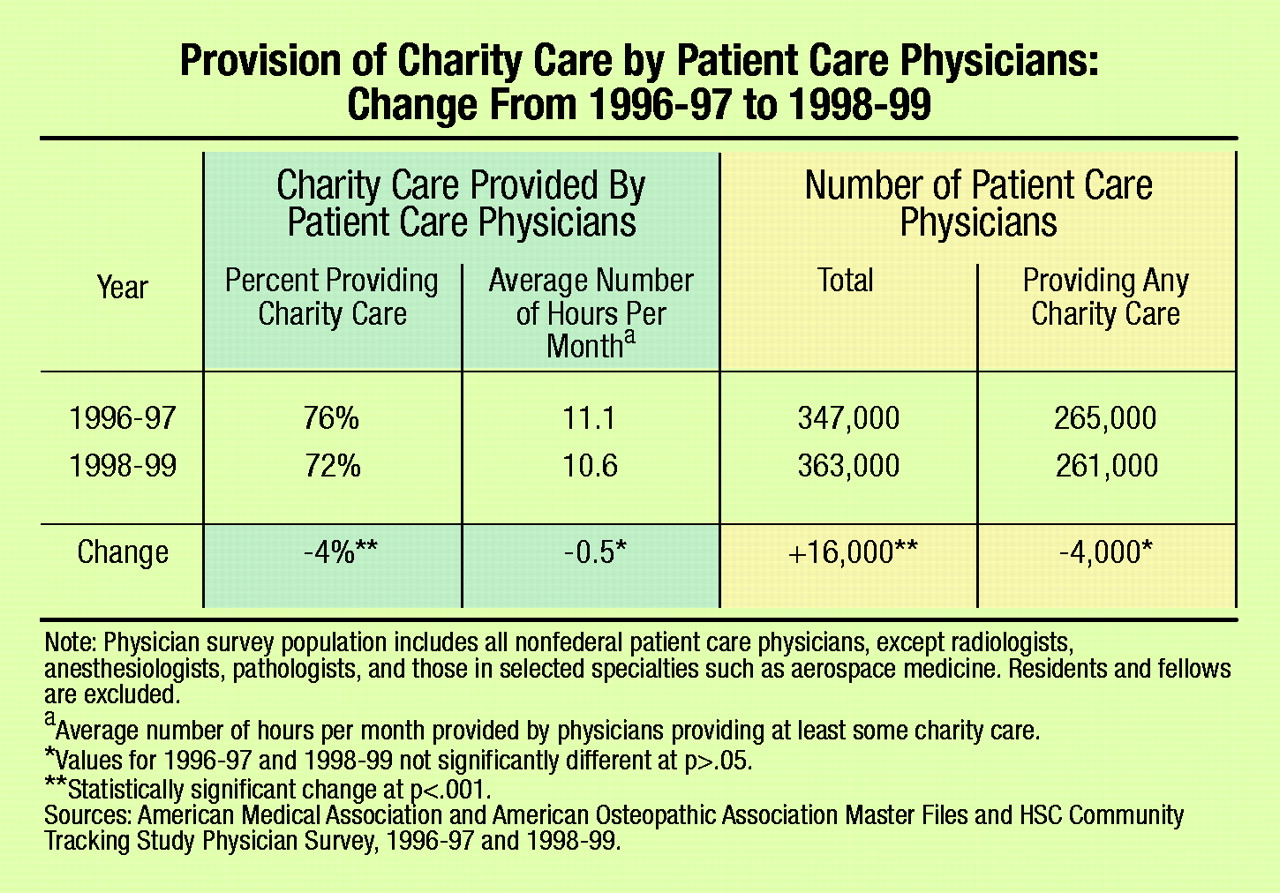

According to a recent issue brief from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), unsettling trends are emerging as physicians grapple with new demands on their time and finances. The HSC found that the proportion of physicians providing “charity care” dropped from 76 percent to 72 percent between 1997 and 1999. The overall number of practicing physicians increased, while the number of physicians providing charity care was essentially unchanged, resulting in a decline in the percentage of those volunteering. The average amount of charity care supplied by physicians who offered care remained constant at about11 hours a month.

The issue brief is one of a series of publications that resulted from the Community Tracking Physician Study. Every two years, the Gallup Organization, under contract with HSC, conducts telephone interviews with 12,000 nonfederal physicians in 60 communities who spend at least 20 hours a week in direct patient care. Both physicians and communities are randomly selected. HSC is a nonpartisan policy research organization funded exclusively by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Implications of Decline

The size of the decrease is not particularly dramatic. In fact, the change did not result in a net decline in the number of hours offered. But the sources of the declining interest in serving the indigent could lead to disturbing future scenarios, according to the HSC analysis.

First, physicians are increasingly working as employees, rather than as owners of their practices. Employed physicians are less likely than owners to provide charity care. During the time studied by HSC, the decline in charity care participation for employees was twice as large as that for physicians who owned their own practices.

HSC speculates that the decline might be due to financial strains associated with managed care practices and increased time pressures from administrative burdens caused by utilization control and multiple payers.

A simulation of the expected proportion of physicians providing charity care indicates that recent changes in several physician and practice characteristics account for approximately 25 percent of the decline in charity care participation.

Psychiatrists React

Data about the provision of charity care by psychiatrists are not available from HSC because the sample does not contain a sufficient number of psychiatrists to draw conclusions. There is a range of opinion, however, about the applicability of the HSC findings for the profession.

Tanya Anderson, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago and associate director of a university-based program that evaluates and treats clients of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services, said, “[Most] indigent psychiatric patients receive care in community-based settings. These services are provided by agencies that hire psychiatrists; that is, they do not rely on volunteer physicians. Many psychiatrists take these positions because of their interest in serving this clinical population. So the trends mentioned in the report probably will have less of an impact on psychiatric patients than on those with other illnesses.”

Lawrence B. Lurie, M.D., chair of APA’s Managed Care Committee, however, has noticed the impact of managed care on allocation of time by psychiatrists.

“I find I spend 20 percent more of my time on administrative matters because of the requirements of managed care,” he said. “Time constraints also seem to be affecting participation in professional organizations.”

Manoj J. Shah, M.D., medical director for the RAP Program at Schneider’s Children’s Hospital and a member of APA’s Committee on Poverty, Homelessness, and Psychiatric Disorders, noted, “The impact of time constraints seems particularly acute in nonprofit medical care settings. During the last two to three years, psychiatrists and other medical personnel have become increasingly subjected to productivity measures. The number of patients we’re supposed to see keeps going up.”

John J. Wernert, M.D., deputy representative for the Indiana Psychiatric Society, concurred about the increased pressure for greater numbers and added, “The large multispecialty groups and hospital systems are losing money and put pressure on psychiatrists and their staffs to avoid indigent or charity care.”

Finally, Hunter L. McQuistion, M.D., pointed to larger issues. He is medical director of Project Renewal Inc., an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and chair of APA’s Committee on Poverty, Homelessness, and Psychiatric Disorders.

“As rank-and-file docs shed charity care, the profession is pushed away from social consciousness and responsibility, which have been part of our historic mission. The trend also can reinforce a certain public myth that physicians are self-interested ‘fat cats’ who don’t really care about people.”

McQuistion believes that the trends could have an even more profound impact on American culture. He said, “Charity care is an advocacy function, and when physicians abandon it, they can lose touch with the elements of society that have the most need for positive contact with mainstream institutions. When there are fewer advocates bridging the gap to the mainstream, society becomes even more desensitized to its own significant problems; for example, class, race, and income distribution.” ▪