Psychiatry, religion, and politics have collided head on in Scandinavia as two U.S. psychiatrists have been drawn into a heated debate in Finland’s parliament over a proposed law that would allow same-sex partners to gain the same rights and privileges as married, heterosexual couples.

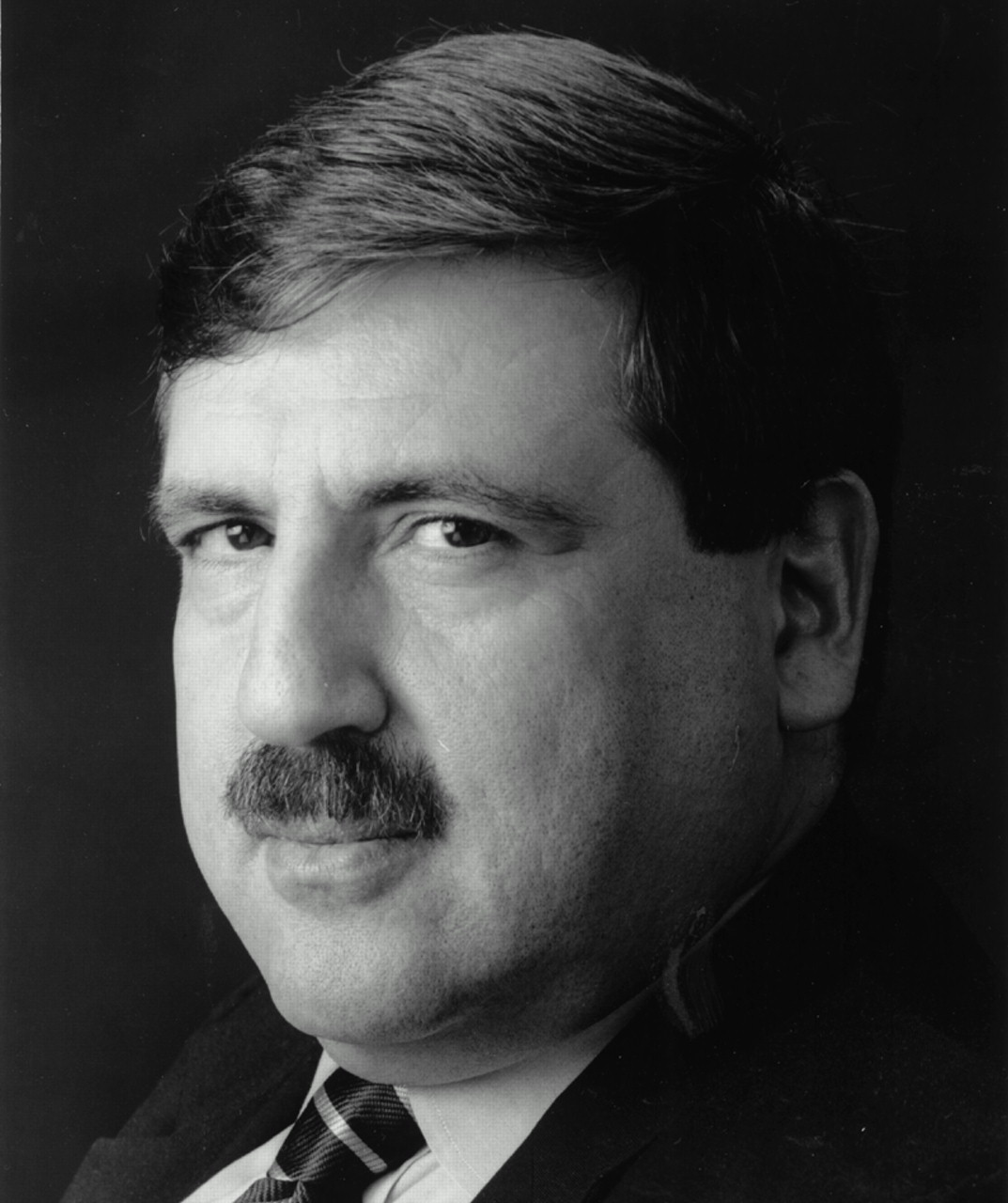

Conservative politicians, particularly those in Finland’s Christian Democratic Party, cited mental health issues as a major factor in their vehement denunciation of the proposal. Thus, supporters in the country’s mental health community turned for help to New York psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Jack Drescher, M.D., chair of the APA Committee on Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Issues and immediate past president of the New York County District Branch.

Drescher was contacted by Finnish sociologist Olli Stalstrom, a member of the Association of Gay and Lesbian Psychiatrists, for input in responding to arguments by bill opponents that APA believes homosexuals can change their sexual orientation through reparative therapies.

Finnish Parliament member Kari Karkkainen introduced that argument during the legislative debate over the same-sex marriage bill. He stated that since a presentation making the case for the efficacy of reparative therapy was given at APA’s 2001 annual meeting, it thus bears the Association’s stamp of approval and should be considered in the debate.

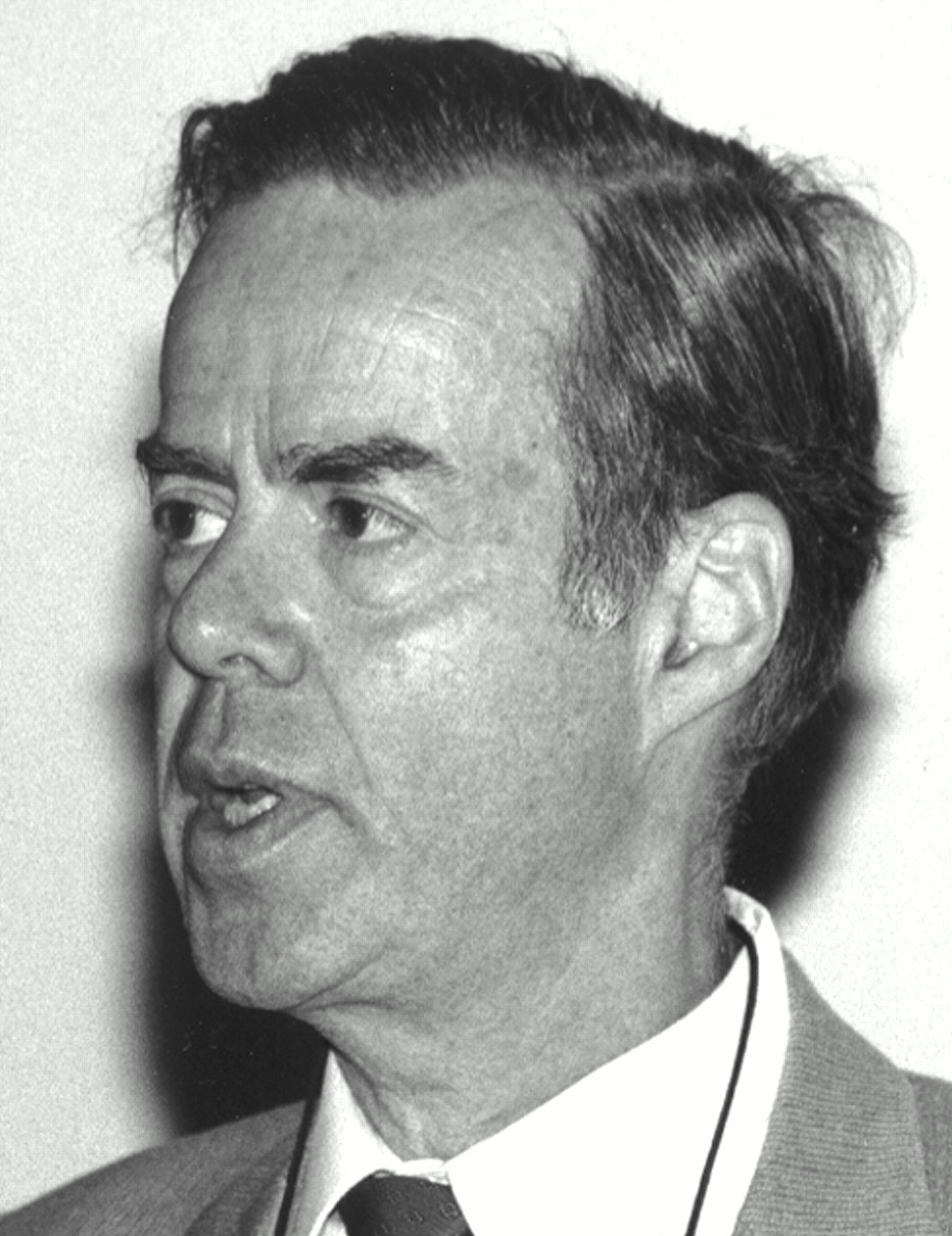

The presentation cited by the legislator was one given at the New Orleans meeting by Columbia University psychiatrist Robert Spitzer, M.D., who chaired the APA work group that developed

DSM-III and revised it as

DSM-III-R.Spitzer had played a key role in ensuring that DSM-III did not classify homosexuality as a psychopathological disorder, as it had been in previous editions of the diagnostic manual. Nonetheless, at last year’s annual meeting Spitzer attracted considerable media attention when he presented data purporting to show that some gay men and lesbians could become heterosexuals after a course of therapy designed specifically to change their sexual orientation (Psychiatric News, July 6).

He did caution that his results were based on self-reports derived from telephone interviews of subjects identified by an ex-gay ministry and thus did not constitute a representative sample of gay men and lesbians. But coming from the psychiatrist who in 1973 argued in favor of depathologizing homosexuality, Spitzer’s recent study has been a touchstone for people who believe homosexuals can change and thus do not deserve civil rights protections or the privileges that society grants married couples.

The opponents of the Finnish marriage bill argued that data show that less than 1 percent of the country’s population is gay or lesbian, and a population that small and “deviant” does not merit legislation granting them the rights that come with married status. They also emphasized Spitzer’s study, saying it was proof that sexual orientation is changeable, and consequently if people want to be married badly enough, they can do so with an opposite-gendered partner.

Spitzer learned from Stalstrom that his study was being misused—an outcome about which he has been concerned since his study was publicized last spring. He then wrote to Karkkainen, the lawmaker leading the charge against the bill, saying that he was “disturbed” that his study results were being “misused by those who are against antidiscrimination laws and civil unions for gays and lesbians.”

Spitzer explained that while his study results run counter “to the current view of most mental health professionals,” who maintain that homosexuals cannot change their sexual orientation, his report was “based on a very unique sample.” Such results “are probably quite rare, even for highly motivated homosexuals,” he said.

He added in his letter to the parliament member that “it would be a serious mistake to conclude” from his research that homosexuality is a “choice.”

He emphasized that he is concerned with “scientific issues” related to sexual orientation, and that he “personally favor[s] antidiscrimination laws and civil unions for homosexuals.”

In an interview with Psychiatric News, Spitzer also rejected the argument made by Finnish opponents of civil unions, as well as some people who hailed his study results earlier this year, that the decision to remove homosexuality as a DSM-III diagnosis was a political decision in which APA succumbed to pressure from gay groups and their allies in the profession. That argument is “nonsense,” he emphasized. “Both sides of the controversy were convinced that science was on their side” when they made their decision.

Drescher responded to Stalstrom’s request for information about APA’s position on sexual orientation by explaining the process by which homosexuality was deleted from the compendium of mental disorders in 1973. He also provided APA’s 1998 and 2000 position statements rejecting claims that reparative and conversion therapies are valid and effective forms of psychotherapy.

Drescher told Psychiatric News, “In 1973 Robert Spitzer’s objective scientific approach to removing homosexuality from the DSM eventually changed the climate for gay and lesbian civil rights. Despite misgivings in the gay community about his recent research on sexual-conversion therapies, his swift efforts to correct the attempted misuse of his unpublished study is an equally important contribution to gays and lesbians worldwide.”

Spitzer told Psychiatric News that he was concerned that his findings would contribute to just the kind of discriminatory argument that arose in Finland, as well as to “coercive attempts to get gays and lesbians who were comfortable with their sexual orientation [into] reparative therapy. . . . Gay people, like anyone else,” he added, “are entitled to full civil rights whether or not some can change their sexual orientation.”

On September 28 Finland’s parliament rejected the arguments against gay civil unions made by the bill’s opponents and voted 99 to 84 to enact the same-sex partnership bill. There were 17 abstentions. The law goes into effect in 2002.

The law permits Finnish couples aged 18 and older to marry in civil ceremonies and register as a couple, which then grants them almost all of the rights of opposite-gender couples.

The exception to the legal protections is that same-sex couples cannot legally adopt children, even if one partner is already a parent.

All of Finland’s Scandinavian neighbors already legally recognize same-sex unions, and Denmark also permits those couples to adopt. ▪