Violent earthquakes struck the small Central American country of El Salvador January 13 and February 13. Registering 7.8 and 6.6, respectively, on the Richter scale, the quakes destroyed entire towns and villages leaving thousands dead or injured.

The quakes are the latest tragedy to hit the country, which is still recovering from a civil war in the 1980s and Hurricane Mitch in 1998, according to Craig Katz, M.D., president of Disaster Psychiatry Outreach (DPO) in New York City.

“El Salvador, with a population of approximately 6 million, seems to have collective trauma and desperately needs mental health assistance,” Katz told Psychiatric News after returning from a two-week visit there in February.

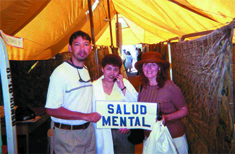

Katz, an instructor in psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, was joined on the trip by Enrique Villareal, M.D., a second-year psychiatry resident at Mount Sinai, and Lynn Delisi, M.D., DPO vice president for research and international affairs and a professor of psychiatry at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

American Jewish World Services (AJWS), a relief and development agency, asked Katz to send a team of psychiatrists to areas of El Salvador affected by the January 13 earthquake.

They were also asked to help develop a mental health program in the country’s western region, where the AJWS has a partnership with a nongovernmental organization (NGO) developing local agriculture, according to Katz. “The NGO realized that the people were traumatized by a series of disasters including the recent earthquakes and weren’t receiving help,” said Katz.

Dearth of Resources

When the team arrived in Usulatan to hook up with the NGO “La Coordinadora,” they were struck by the region’s poverty. “There was no running water or bathrooms, and the children ran naked on the streets alongside cattle, pigs, and roosters,” said Delisi.

The DPO members discovered that the people were understandably anxious about aftershocks and possible earthquakes. They trained local teachers and health care workers how to reduce anxiety including implementing earthquake drills, said Delisi.

There are about 40 psychiatrists in El Salvador, mainly in private practices in the capital of San Salvador.

The bulk of mental health care is provided by general practitioners from the Ministry of Health who travel in teams to rural areas. However, the general practitioners’ knowledge of mental health treatment and psychiatric drugs is quite limited, the team discovered.

“We taught them how to use the new atypical neuroleptics and gave them some to keep. The general practitioners referred patients to us for treatment of depression, psychosis, and anxiety,” added Delisi.

More severe psychiatric cases are referred to the sole public psychiatric hospital in the capital, said Katz.

When he, Delisi, and Villareal visited the hospital, they were shocked by what they saw. “Some patients were in severe catatonic postures, immobile, and mute, while others were speaking in mumbo-jumbo.”

Patients were given high doses of older neuroleptics because the doctors were unfamiliar with atypical antipsychotics such as clozapine and olanzapine, said Delisi.

“There was one psychiatrist per 100 patients and not many support staff. They did not have a pharmacy or library other than a few outdated journals,” said Delisi.

She plans to send the hospital updated psychiatric literature and newer psychiatric drugs.

The team also found that mental health professionals working with people displaced by the earthquake were unfamiliar with structured interviews.

The team taught psychology students working in a makeshift camp in the capital to use the interviews to assess the victims’ mental health needs. “The results [of using the interviews] showed that 40 percent of the individuals who were interviewed needed treatment. There was significant anxiety, insomnia, depression, and suicidal ideation,” said Delisi. “We gave the doctors from the Ministry of Health a list of the people needing treatment so they could follow through.”

Second Earthquake

They heard on the car radio that the southeastern part of the capital was the hardest hit and drove to the hospital in San Vicente, where the injured were being taken, to offer their help, said Delisi.

There they encountered a scene reminiscent of the movie “M*A*S*H.” Hundreds of injured people were brought to an open courtyard area, said Delisi. “There were no antibiotics, and medical students were stitching wounds without anesthetics.”

“We worked with a translator to evaluate and stabilize as many people as we could and gave the health workers the antibiotics we brought,” said Delisi.

A common theme expressed by the victims was a sense of apathy and hopelessness about their future, said Delisi. “We learned anecdotally that alcoholism and domestic violence had risen since the earthquakes began,” said Delisi.

Katz believes that a large mental health effort in El Salvador could empower the people to make changes in their lives and reduce their apathy and extreme poverty.

The DPO team proposed starting a pilot mental health project in Usulatan to a committee of psychiatrists advising the Ministry of Health. The committee hasn’t responded yet, but DPO plans to proceed with the support of the psychiatrist dean of the University of El Salvador School of Medicine.

“A psychiatrist trainee at New York University has volunteered to spend a year in Usulatan in July when he finishes his residency. He could consult to primary care clinicians, teach psychiatrists at the national psychiatric hospital, and develop a mental health system based on the resources available,” said Katz.

“We also envision sending psychiatric residents to Usulatan to do rotations at the primary care clinics,” said Katz.

He found the trip deeply rewarding. “Innovations that we take for granted here such as structured interviews make a big difference there. The professionals we met were eager to learn and welcomed us enthusiastically,” said Katz.

El Salvador was DPO’s first international venture. “We want to provide more assistance nationally and internationally, but need more volunteers,” said Katz.

Information about DPO, including e-mail addresses for Katz and Delisi, is available at www.disaster-psychiatry.org. Katz’s phone number is (212) 860-8665, and Delisi’s is (631) 444-1612. ▪