John O’Reardon, M.D., a native of County Kerry, Ireland, sits in his small, cozy office on the third floor of 3535 Market Street in Philadelphia and smiles an impish smile. Yes, he does have an Irish tale to tell—how he has come from milking cows in Ireland to banishing refractory depression with the use of a magnet on Philadelphia’s “Avenue of Technology,” as Market Street is nicknamed.

“I was born in County Kerry, Ireland, in—oh dear, maybe it’s encroaching middle-aged vanity, but can you fudge it?” He chuckles while wisps of prematurely graying hair rise above his high forehead.

“My two brothers and I had to milk the cows every morning, harvest the hay, and otherwise work hard manually,” he continues, “but our father, a part-time farmer and office worker, and our mother, a homemaker, heavily emphasized education for us boys as well, because in Ireland, as in many parts of the world, your ticket to future economic prosperity rests heavily on your education.”

In fact, one of O’Reardon’s brothers became a teacher, the other became a manager of a company, and John decided to become a physician—the first member of his family to do so. He attended medical school at University College Cork, graduated in 1984, and worked as a primary care physician. As time went on, he became increasingly interested in psychiatry.

“Really, some of it was the nature of primary care itself,” he explains, “where you see a lot of psychiatric problems, often presented psychosomatically. And primary care shares with psychiatry the continuity of care where you see people long term or within families.”

So in 1989 O’Reardon decided to start training in psychiatry. He went to London and worked at the Godden Green Clinic, a private psychiatric hospital. He also got trained in cognitive analytical therapy. This is a type of therapy, well established in Britain, that integrates cognitive and psychodynamic approaches in a brief psychotherapy. By 1993 he was a psychiatrist, as well as a primary care physician.

America Beckons

Around this time, both O’Reardon and his wife, a physical therapist, became interested in emigrating to the United States. One reason O’Reardon found the idea appealing, he says as he gesticulates to make the point, is that he was attracted to the United States for its diversity as well as for cultural and intellectual stimulation. Moreover, he says, he was thinking of devoting a good part of his future to psychiatric research, and he believed that research opportunities would be richer in the United States than in Ireland.

But there is a great chasm between wanting to emigrate to America and actually doing so, the O’Reardons were well aware. At that time, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service offered visas through a lottery to 50,000 nationals from 19 countries around the world. But for their visa applications to be entered into the lottery, the applications had to be sent by surface mail and arrive on a specific day in Washington, D.C. However, that first year of the program, applicants were allowed to submit more than one application. So O’Reardon and his wife—“neither of us feeling that we were particularly lucky when it came to lotteries,” O’Reardon recalls—mailed 1,000 applications each. “And the irony is that one of my wife’s applications was selected from the lottery, whereas none of mine were,” O’Reardon says with a smile. “So I qualified to come to the United States only on the basis of being her dependent.”

O’Reardon experienced other difficulties as well. For instance, he recalls, “at the time that I applied for residency in the United States, which was 1993, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology recognized a PGY-1 year completed in internal medicine but not in family medicine, which was my primary care background. In our part of the world only family medicine is considered true primary care, and everything else is specialty. So because of this I had to do a PGY-1 year or internship. How much psychiatry I did was up for negotiation between me and the residency program director of whichever residency program I got into. I decided to do the full additional three years of residency (though I know some overseas colleagues who were able to shorten it by a year) as I wanted to get into the very best American program possible, that is, not cut any corners, and as I wanted to get the maximum possible out of my American training.”

So O’Reardon did an internship and three years of residency at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School from 1993 to 1996. Then he did fellowships in psychopharmacology and cognitive therapy at the university. “I am what you might refer to as overtrained,” he says good-naturedly.

It hasn’t been all that easy getting established as an American psychiatric researcher, either, he concedes. “The biggest challenge for a young researcher is to find funding. How can you—as you finish your training and start to get research experience—support yourself in that interim period? Even a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression grant, which I have, would support you only one day a week for two years. So that means that you have to spend a lot of time on clinical work to support yourself, and while you are doing clinical work, you still have to generate hypotheses and pilot data that will get you to the point that some of the things you are researching are worth funding. And what’s more, you don’t have the support and staff that older scientists have.”

Happy With His Decisions

Still, he says that he is happy with the decisions he has made—coming to the United States, repeating his psychiatric training, joining the University of Pennsylvania Medical School staff, and conducting psychiatric research, especially on treatment-resistant depression, at his Market Street office, which is home to a number of University of Pennsylvania psychiatric investigators.

“All the research I do is clinically based,” he says. “I really like patients.”

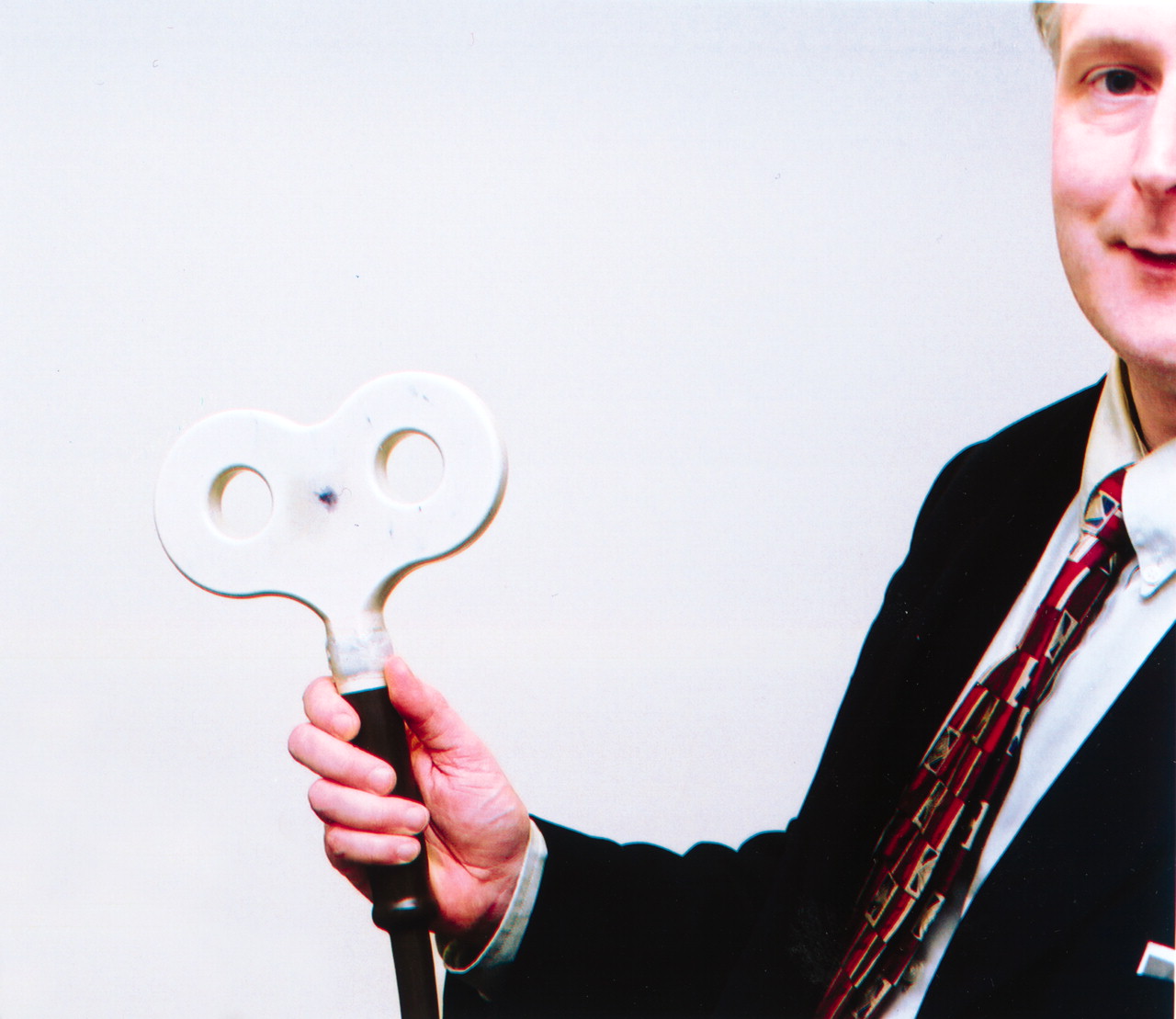

For instance, one of the research areas in which he is engaged is repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Several groups of investigators have reported that rTMS, which consists of placing a magnetic coil over the left frontal scalp of a conscious patient to stimulate the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of the brain, can banish treatment-resistant depression if it is given in 20-minute sessions, five days a week, for two to four weeks. In fact, the technique was approved as a treatment for treatment-resistant depression in Canada last year. If it is ultimately approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, it will likely prove to be an attractive alternative to electroconvulsive therapy in many cases because, unlike ECT, it requires no anesthesia and is believed to cause no cognitive or memory difficulties. It would also be a viable alternative to medication because side effects are minimal—occasional mild headaches, no gastrointestinal symptoms, and, very crucially, no sexual dysfunction (which is a big negative for patients who stay on antidepressants over the long term).

O’Reardon is now studying rTMS in a group of patients with treatment-resistant depression. He leads his visitor from his office to a small room nearby where subjects come for the experimental treatment. Each subject sits in the large, comfortable, green vinyl chair while O’Reardon uses the electromagnetic coil to generate the magnetic field that stimulates the subject’s brain.

O’Reardon gives subjects who respond favorably to rTMS what is known as a “serotonin stress test.” This is a test to see whether the neurotransmitter serotonin was involved in their rTMS treatment response.

If it turns out that serotonin is involved in the response, O’Reardon explains, that discovery would help clinicians provide more effective treatments to patients with treatment-resistant depression. For instance, if it turns out that rTMS counters depression by stepping up the production of serotonin, then patients who respond only partially to rTMS probably do so because their depression is only partially due to a serotonin deficiency. In that case, giving them not just rTMS but a medication that increases production of another neurotransmitter in their brains—say, norepinephrine—might possibly be just the combination needed to banish their depression.

“My goals,” O’Reardon concludes as he bids his visitor goodbye, “are to better understand how rTMS and other therapies for treatment-resistant depression work. And I also want to collaborate with other investigators to develop combined treatments for treatment-resistant depression, including psychotherapy as well as biological treatments like rTMS and medication, since treatment-resistant depression afflicts a huge number of individuals.

“People say, ‘It must be depressing to research treatment-resistant depression.’ But I say, ‘It’s a lot of fun because every subject is different, always a challenge.’ And when you help them, it’s immensely rewarding because they have been suffering for a long time.” ▪