Psychiatry residents at New York area hospitals were some of the first people to come to the aid of victims of last September’s terrorist attacks (Psychiatric News, November 2, 2001). A year later, they reflected on the learning experience of a lifetime.

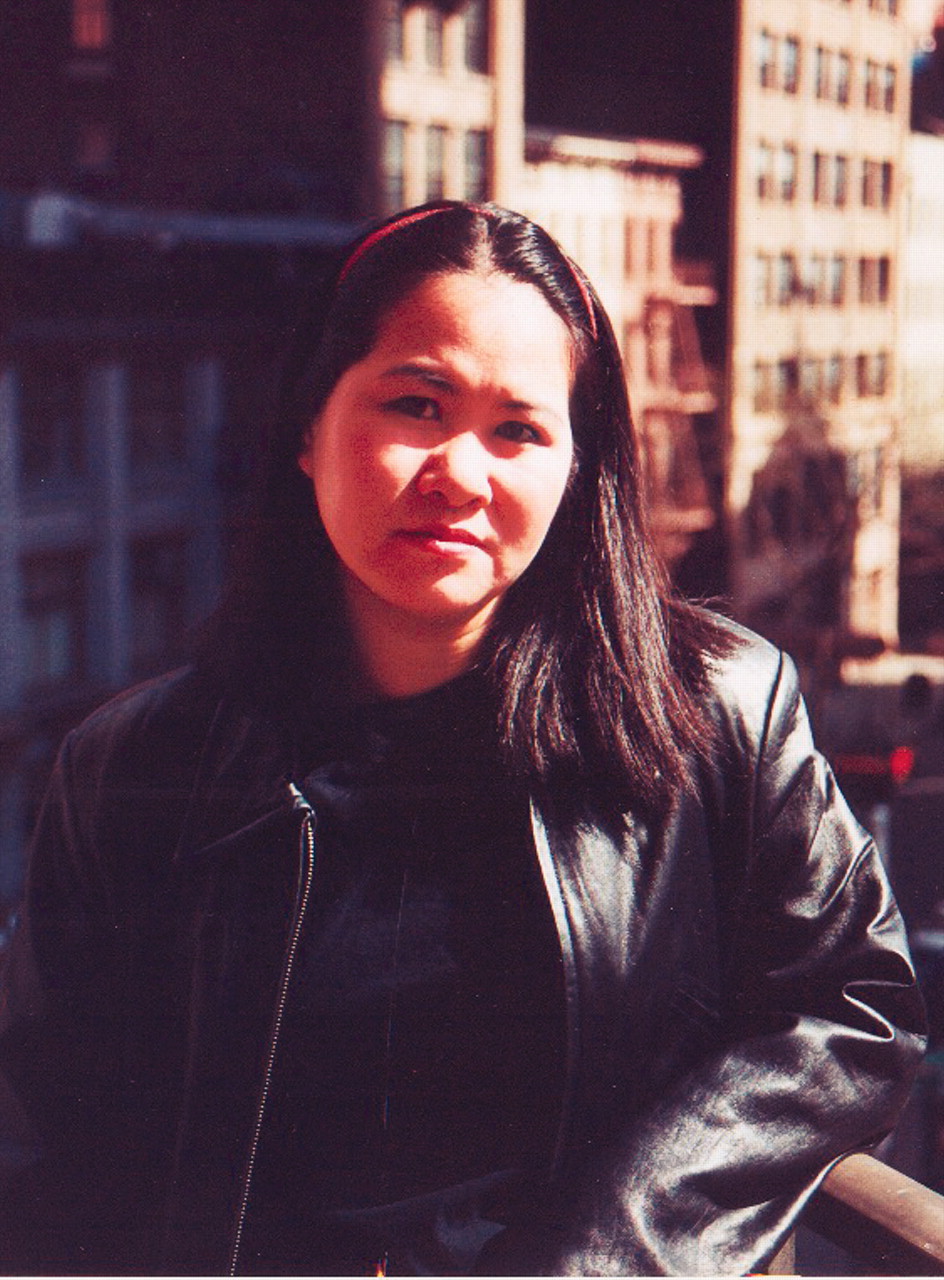

For Pearl Louie, M.D., who was then co-chief resident at St. Vincent’s Hospital, the chaos that would dominate the next several weeks started with a disaster drill sounding throughout the hospital.

Through a nearby window Louie saw the first World Trade Center building fall as she presented a patient to an attending physician. “Soon, we weren’t really sure of what our duties were anymore,” she told Psychiatric News. “We were required to think on our feet and rely on common sense.”

Some of the people who began filing into the emergency room were employees who had escaped from the World Trade Center buildings just before they collapsed. They were stunned and in shock.

“It was difficult to concentrate on work while wondering about how our family and friends were doing,” said Louie. “It was hard to eat and sleep for a while.”

In the weeks that followed, Louie came to admire the resiliency of her patients. “They were so determined to keep their appointments that they snuck past police barriers set up around the hospital and near ground zero.”

Louie discovered a common bond with her patients. “This was the first time I ever shared trauma with my patients—I could identify with what they were saying.”

Louie, who is now working at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston as a medical psychiatry fellow, said the experience taught her “not to take anything for granted—my friends, family, work, or the city of New York.”

“How ironic,” she added, “that an act of such hatred brought so much kindness out of people in the community. . . .A community bound by grief and horror.”

Renee Seto, M.D., another resident at St. Vincent’s, found that her regular patients were more anxious and depressed after the attacks. When she’d ask them how they were feeling, they’d echo her concerns back to her.

“They would say, ‘I was worried about you,’ ” Seto recalled. “At that point, the doctor-patient boundary becomes blurred. We were all living through this together.”

Seto spent free time counseling firefighters for a few months, but eventually had to stop. “Every week, I’d be retraumatized,” she said. “I’d hear these horrific stories and have to deal with emotions just pouring out of these men. It was hard to listen to that and not want to cry myself.”

For Rhea Parandelis-Santiago, M.D., a resident working at Bellevue Medical Center in New York, free time was spent at the New York Armory, where families came to receive counseling services.

As she worked, she felt close, interchangeable even, with those around her. “Though we were an interdisciplinary team, we were the same,” she said. “We had the same words, the same lists—it was a unifying experience.”

At the armory she translated for a Latino man who came from Florida by train. His trip was prompted by a short cell-phone conversation that typified the horror of the terrorist attacks. “This man’s cousin was trapped in the rubble. He called and said ‘Come find me,’ ” said Parandelis-Santiago. The Florida relative was “wide-eyed, in shock, and alone.”

Heather Morse, M.D., a PGY-2 resident at New York University (NYU), told Psychiatric News that when it comes to 9/11, “I’m just another New Yorker.” She said that at the time of the attacks, “it was hard to believe that those raw, painful feelings could ever fade, and it seems strange now that they have.”

She recently scheduled an appointment for one of her patients on the one-year anniversary of 9/11 and found herself asking the patient, “Are you sure you want to come in that day? You know, it’s September 11th.” Morse added that perhaps she was feeling unsure herself if she wanted to see patients that day because she didn’t know how difficult it would be for her.

Hamilton Holt, M.D., another PGY-2 resident at NYU, said that seeing the towers fall as he watched from the 16th floor of the New York Veterans Administration Medical Center was a “terrible, life changing experience.”

The day of the attack was eerily quiet, he said. “We saw people coming back from the site of the attacks past the VA hospital, and could smell it in the air, but there was nothing for us to do.”

He remembered his thoughts before the attacks. “Thinking about clothes, movies, elevator rides—everything suddenly seemed so tiny.”

Over the next weeks, Holt led current-event discussion groups with his severely ill patients, who sometimes processed the attacks through a filter of psychosis. “For example, we had discussions about the idea that anthrax is caused by AIDS, the role of religion and philosophy in our world, and what the U.S. may have done to cause the attacks.” Holt said that there were some interesting ideas discussed, and that “the conversation became quite lofty at times.”

“My patients comment on 9/11 with anger, loss, and uncertainty in direct relation to the chaos or sadness they were feeling,” he said.

“I’ve been thinking about the anniversary of that terrible day in mostly positive terms—we’re wiser, . . .more vulnerable, and more human. And we’re still here.” ▪