Denial may be keeping millions of Americans who are in need of substance abuse treatment from seeking help, according to new findings from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse.

From 2000 to 2001, the need for substance abuse treatment among people over age 12 rose significantly, according to the survey. While 4.7 million people, or 2 percent of the U.S. population, needed treatment in 2000, an estimated 6.1 million people, or 2.7 percent, did in 2001.

Of the 5 million people who needed but did not receive treatment for an illicit drug problem in 2001, just 377,000 believed they needed it. (Need was determined from responses to questions involving DSM criteria.) That leaves almost 4.6 million people who did not think they had a problem with illicit drugs, according to the survey report.

“The denial gap is one of our biggest treatment problems,” said John Walters, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, in a September press conference in Washington, D.C.

The conference marked the 13th annual observance of National Drug and Alcohol Addiction Recovery Month and the release of the findings from the 2001 National Household Survey. “This is why people cannot seek help alone,” he said.

Walters appeared with Secretary of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson and with Charles Curie, who is the administrator of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

SAMHSA has conducted the survey every year since 1971 to capture data on the use of illicit drugs, alcohol, and tobacco from a representative sample of people aged 12 and older.

Last year researchers interviewed almost 70,000 people in their homes as part of the data-collection process.

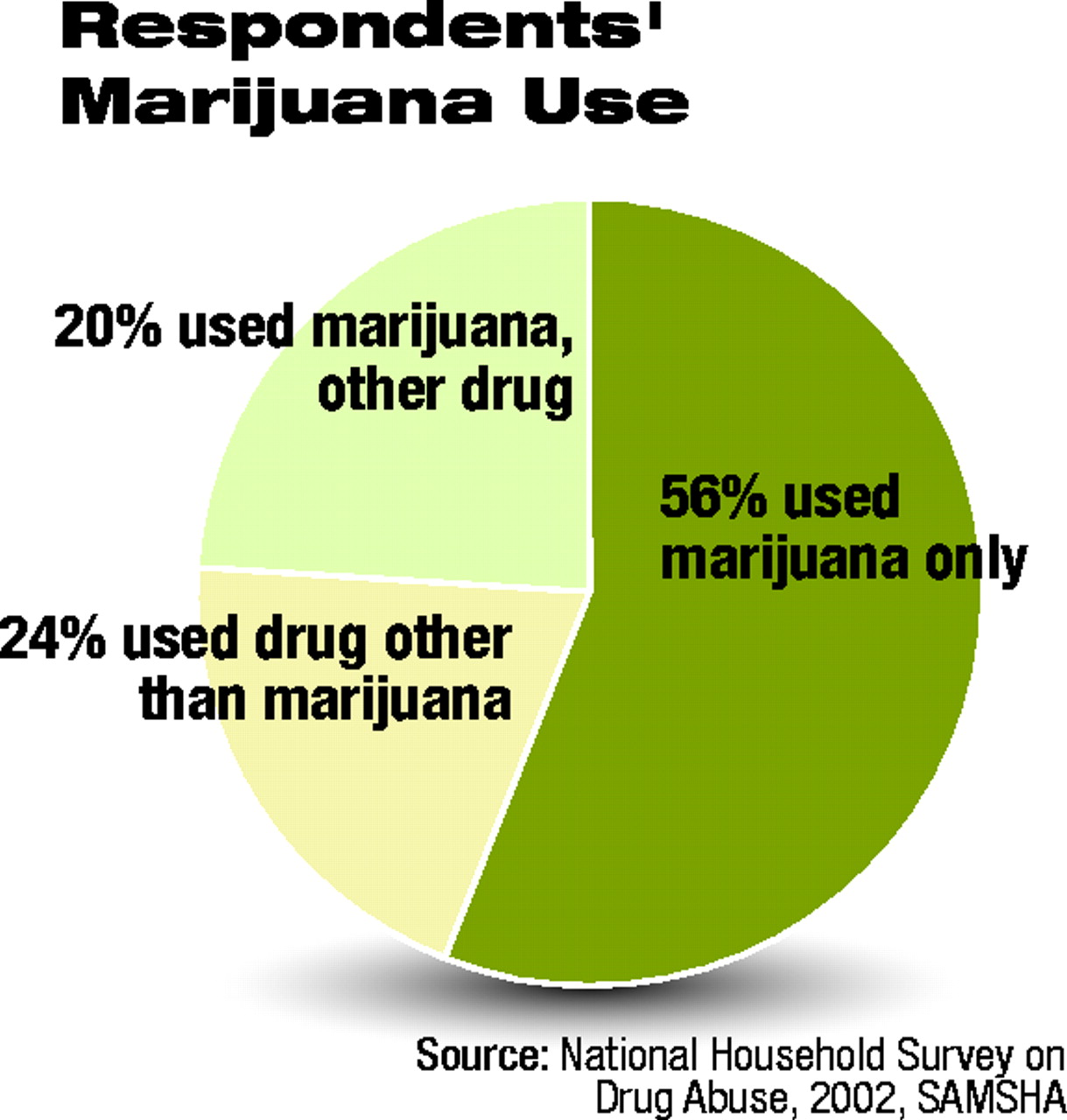

The trio expressed concern over the survey’s marijuana-related findings. Between 2000 and 2001, current marijuana use for people aged 12 and older rose from 4.8 percent (10.7 million) to 5.4 percent (12.2 million). Marijuana users account for over three-quarters of the 15.9 million drug users in the United States. All findings relating to marijuana also include hashish.

In addition, the survey showed that of all illegal drugs, marijuana is the biggest source of dependence—62 percent of the 5.6 million Americans who were dependent on illicit drugs were dependent on marijuana.

“Marijuana is not some harmless chemical toy, but a clear and present danger to the health and well-being of all who use it,” said Thompson.

Walters linked the increase in marijuana use over the past year in part to a widening perspective within the American public that marijuana is more or less a benign drug—an attitude the survey also measured. He noted that many baby boomers who saw the propaganda film “Reefer Madness” as college students may continue to feel that there is a great deal of unjustified concern about marijuana.

He noted that in the 1970s the level of THC, the active ingredient in marijuana, rarely topped 1 percent. “On the street today,” he said, “you can get hybrids with 15 to 30 percent THC content.”

For the first time in the survey’s history, the researchers collected data on the prevalence of serious mental illness, which they defined as someone “having a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder and functional impairment that interferes with major life activities.”

In 2001 there were an estimated 14.8 million adults aged 18 and older with serious mental illness, representing 7.3 percent of all adults. Of this group, 6.9 million people received mental health treatment in the year prior to the interview.

Among adults with serious mental illness in 2001, an estimated 3 million had both serious mental illness and substance abuse or dependence.

About 4.3 million youth aged 12 to 17 received treatment or counseling for emotional or behavioral problems in the prior year. The most common reason for the most recent treatment session was that the youth “felt depressed” (45 percent), followed by “breaking rules or acting out” (22.4 percent), and “thought about or tried suicide” (16.6 percent).

If there was any good news from the survey, it was that smoking initiation rates are down among young people.

While in 1997 there were 1.1 million new smokers aged 12 to 17, this number dropped to 750,000 in 2000.

Young Rock DiSessa posed quite a contrast to his fellow speakers at the conference. The 20-year-old from Oakland, Calif., delivered the same message as his elders, but in quite a different way. He had once been addicted to drugs and came away from the experience determined to help others in the same situation. He began to drink and smoke at the age of 10, and he rapidly progressed to substance abuse. “Things like family, school, and sports seemed to lose their priority,” he said.

At age15, he decided he needed help. “By that time, I’d been kicked out of the house and was living with relatives—my life had crumbled into basically nothing.”

He turned to his mother for help, but before they could arrange treatment, the police arrested DiSessa. The teenager wound up on a court-ordered inpatient stay, which led to outpatient treatment. “I am grateful that my family was involved,” he said.

It is now four years later, and DiSessa says that his life is full. “I’m attending college, getting good grades, and I’ve been working for a year and a half—before that, the longest I held a job was 20 days.” He said his relationships with others have improved as well. “The things that are important to me are back,” he said.

The results of the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse are posted on the Web at www.drugabusestatistics.samhsa.gov. ▪