The National Institutes of Health, under its National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) branch, has put together a network of 11 top brain research centers to serve as the foundation for a new brain-imaging network. For the first time, images from hundreds of patients across the country with schizophrenia will be compiled in a federated database, allowing direct comparison of images between patients.

In late October, the latest in a series of grants was awarded by NCRR to create a joint general clinical research center (GCRC) at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of California, Irvine. That GCRC will be responsible for creating a unique, $10.9 million database of human brain images from 11 brain-imaging centers across the country (

see box). The project will utilize new technology developed by the consortium of research universities, the Biomedical Informatics Research Network (BIRN), also developed with NIH funding.

The initial project, dubbed FIRSTBIRN (Functional Imaging Research in Schizophrenia Testbed), will be led by Steven Potkin, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and the Robert R. Sprague director of the brain imaging center at the University of California, Irvine.

“This is a massive project that includes numerous institutions with many extremely talented researchers who have made major contributions to make this effort advance, and the whole will absolutely be greater than its parts,” Potkin told Psychiatric News.

Basic Data to Be Shared

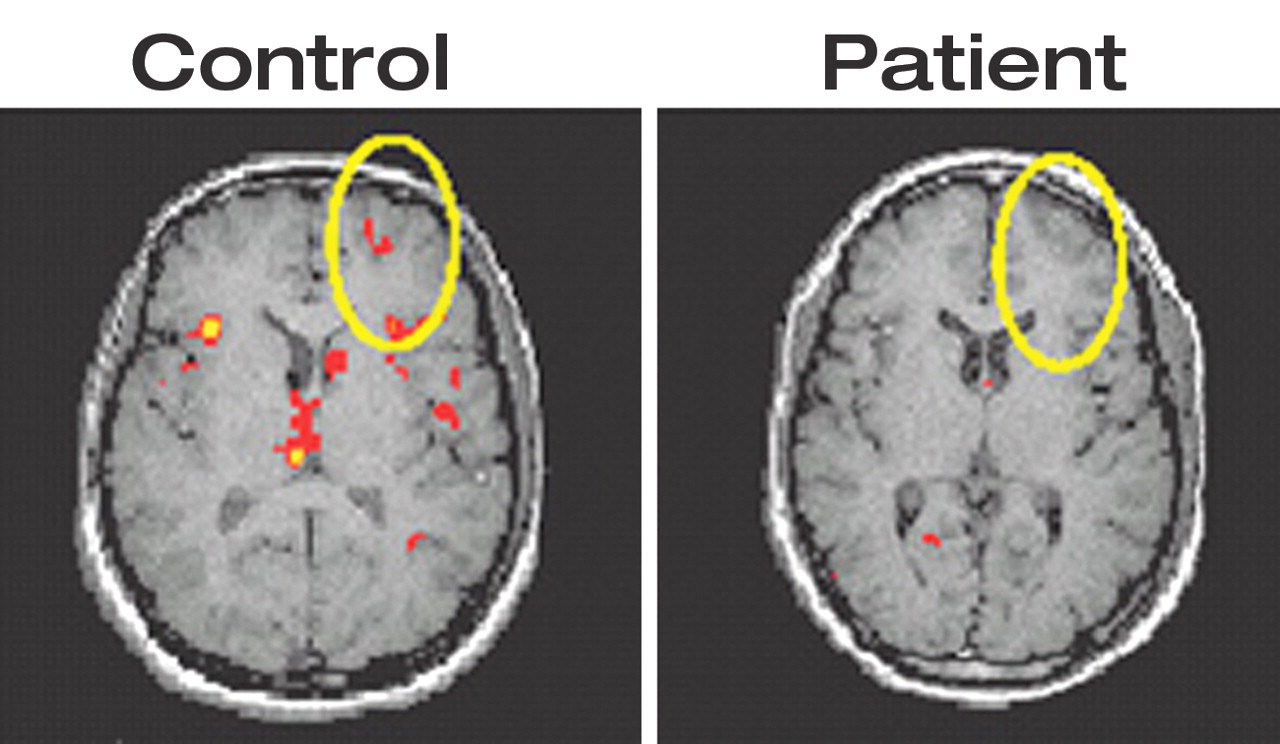

Until now, brain imaging has been quite variable from one imaging center to the next, Potkin explained, and indeed, even from one individual to another or from one imaging session to the next of the same patient.

“Each center has specific machines with different magnet strengths and different outputs. And because we are talking about functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI] here, the patients are doing something while they are imaged—so you’ve got different tasks being done at different centers under different protocols. [Thus,] it has been impossible to share images and compare them from one site to another or, indeed, from one patient with schizophrenia to another patient with schizophrenia. As a result, the literature says, maybe one study says this and one study says that.”

FIRSTBIRN will attempt to “equalize all those variables.” Researchers will be able to download into the database images taken at any of the 11 sites, and the images will be coded such that the database will know which center the image is from, what scanner and image settings were used, and what task was performed by the patient during the functional imaging. The system will be able to account for the differences in those variables between sites, according to Potkin.

The three-year grant provides for a multistep process to allow the comparisons to occur. First, images will be produced at each site of a mechanical phantom, an inanimate object of defined size and shape to standardize a comparison between different imaging settings on the different machines at different sites. Next, a small group of “human phantoms” will be imaged at all sites.

“The same five individuals will go to all the sites and be imaged, doing a common task under the same exact protocol at each site,” Potkin detailed. That, he said, will help the database account for variability between humans doing the same task.

Endless Questions

“Then, to test normal and to test patients,” Potkin said, “there is a ‘consortium task’ that has three parts to it.” Each patient imaged for FIRSTBIRN will do a specific motor task, working memory task, and auditory task. “This will allow us to look at the two most implicated brain areas in schizophrenia, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the superior temporal gyrus.”

The “consortium task” can be done before treatment, after treatment, on different age groups, on patients at first episode, or on patients who have been ill for years—Potkin said the possibilities are endless.

“Now that we’ve taken care of the variability in the imaging, we can ask questions like these: When do the frontal lobe abnormalities come into play, at first episode or only after chronicity? When do the superior temporal gyrus abnormalities appear? Are these abnormalities affected by active symptoms or drug treatment, and if so, how?”

But, Potkin emphasized, if the project were limited to the “consortium task,” it would certainly be a tremendous scientific breakthrough. “But, there are two more parts.”

In addition to the defined consortium task, each site also has its own unique protocols that have been developed over a number of years. None of the researchers would want any of those protocols abandoned. Each site will continue to image patients using its own protocols as well and will download those images into the FIRSTBIRN system.

“This is what I call the ‘value-added science,’ ” Potkin said. Because of the ability of the system to compare individual images between sites, the system should also be able to compare images done at different sites using different protocols, as long as it knows exactly what the differences are.

Potkin said that schizophrenia was chosen for FIRSTBIRN because of the disease’s complexity and devastation.

“This is a wonderful model to apply to a really tough problem using all of the advances we have in imaging, and it will be a model that will be applicable to many brain illnesses,” he said.

More information on BIRN and its projects is posted on the Web at www.nbirn.net/ and www.nbirn.net/Projects/Function/BACKGRNDFIRSTBIRN10_29_02.pdf. ▪