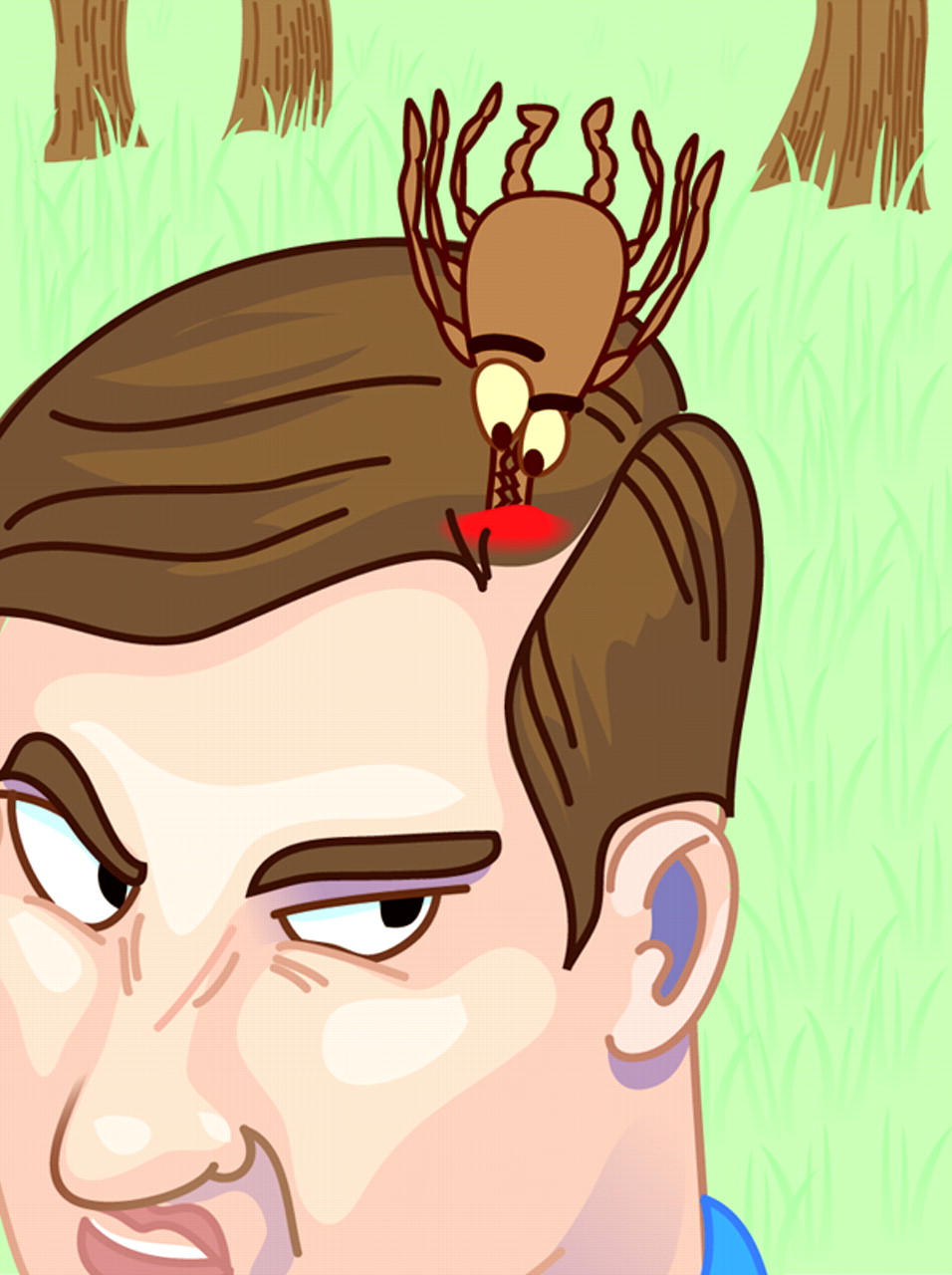

Lyme disease is no small health threat to persons living in the Northeast, the Mid-Atlantic states, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and northern California. True, the first signs of its onslaught are usually no more than flulike symptoms. But it is also capable, over the long haul, of inflicting a variety of other physiological insults—say, muscle pain, arthritis, heart inflammation, severe headache, stiff neck, or facial paralysis.

Now a new study adds one more malady to that list: psychiatric illness.

The study was conducted by Tomáš Hájek, M.D., a psychiatry resident at the Prague Psychiatric Center in the Czech Republic, and his colleagues. It is reported in the February American Journal of Psychiatry.

There were several reasons that Lyme disease piqued the interest of Hájek and his colleagues. For one, Lyme disease is the most frequently recognized anthropod-borne infection of the central nervous system in Europe, as well as in the United States. Second, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease—Borrelia burgdorferi—belongs to the same family as does the bacterium that causes neurosyphilis. Around 1900 neurosyphilis accounted for some 10 percent to 15 percent of psychiatric hospital admissions, but because of penicillin treatment, it is now an uncommon disorder. And third, anecdotal reports have suggested that Lyme disease can lead to psychiatric consequences—say, mood changes or depression.

Hájek and his coworkers decided to undertake a study to explore this possibility by comparing the prevalence of antibodies to B. burgdorferi in psychiatric patients with the prevalence in healthy comparison subjects. If a higher prevalence of such antibodies were found in the former, they reasoned, it would bolster the case that Lyme disease can lead to psychiatric illness.

They recruited more than 900 psychiatric patients admitted to the Prague Psychiatric Center between 1995 and 1999 for their study. About a third of the patients had anxiety disorders, a third mood disorders, a quarter schizophrenia or other psychotic diseases, and the remaining subjects personality disorders, delirium, dementia, or other conditions. All of the patients agreed to have samples of their blood screened for antibodies to Lyme disease. The researchers also selected some 900 healthy subjects to serve as controls. These individuals had been recruited during the same period for an epidemiological survey of antibodies to B. burgdorferi in the general population of the Czech Republic.

Blood samples from the approximately 1,800 subjects were then sent to the National Reference Laboratory for Lyme Disease of the Czech Republic. The samples were analyzed to see whether they had antibodies reacting against B. burgdorferi. Two different types of antibodies were scrutinized. One was IgM antibodies, which move into gear early against an infection. Another was IgG antibodies, which peak some six weeks after an infection has set in.

Hájek and his team then compared the prevalence of IgM antibodies directed against B. burgdorferi in the psychiatric subjects with the prevalence in the control subjects. They found that 30 percent of psychiatric subjects had IgM antibodies to the bacterium, whereas only 10 percent of controls did—a highly significant difference. They then compared the prevalence of IgG antibodies directed against B. burgdorferi in the psychiatric subjects with the prevalence in the control subjects. They found that 5 percent of psychiatric subjects had IgG antibodies to the bacterium, whereas only 2 percent of controls did—again, a significant difference. When they pooled these data, they found that 36 percent of psychiatric subjects, but only 18 percent of controls, had at least one kind of antibody to B. burgdorferi.

These results thus implied an association, perhaps even a causal link, between Lyme disease and psychiatric illness.

However, Hájek and his colleagues went further to determine whether the relationship they had found was real. They matched some 500 psychiatric subjects with some 500 control subjects on the basis of age and gender—two possibly confounding factors—and compared the prevalence of antibodies to B. burgdorferi in the two groups. Once again, the results implied a link between Lyme disease and psychiatric illness. Whereas some 33 percent of psychiatric subjects had at least one kind of antibody directed against B. burgdorferi, only 19 percent of controls did—a highly significant difference.

“These findings support the hypothesis that there is an association between B. burgdorferi infection and psychiatric morbidity,” Hájek and his team concluded in their study report. “In countries where this infection is endemic, a proportion of psychiatric inpatients may be suffering from neuropathogenic effects of B. burgdorferi.”

Richard Balon, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit, worked at the Prague Psychiatric Center a number of years ago. Psychiatric News asked him to comment on the center and the quality of research done there.

“It is a solid place, with a good reputation, and finally, with a group of young, enthusiastic researchers such as Hájek,” he said.

Ivan Tùma, M.D., Ph.D., a psychiatrist with Charles University School of Medicine in Hradec Kralove, the Czech Republic, expressed sentiments to Psychiatric News that were similar to those of Balon: “The Prague Psychiatric Center is the prestigious clinical and research center of the Czech Republic. . . .[So] I personally have no doubt about the quality of work done there.”

As far as the results that Hájek and his colleagues obtained, Balon had this to say: “They are both interesting and important. Of course they need to be replicated to make sure that they are solid.”

Indeed, “the results of the study are rather surprising and provocative,” Tùma opined. “I hope it will lead to replication in other parts of the world.”

Even if Lyme disease turns out to be capable of triggering psychiatric illness, of course, some important questions need to be answered. For instance, what types of psychiatric disorders can it provoke?

“It would be interesting,” Balon said, “to see the comparison of seropositive and seronegative psychiatric patients with regard to diagnosis.”

Tùma made a similar comment: “Although several studies have suggested that cognitive deficit is a symptom in Lyme disease, it is not clear whether this impairment is general or relates to specific cognitive functions. It would be interesting to examine the cognitive functions in both seronegative and seropositive groups.”

Also, could early antibiotic treatment prevent Lyme disease from leading to psychiatric consequences? It would be valuable, Balon noted, “to see how patients who get early antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease compare psychologically with those who get later treatment or none at all. That would have a bearing on decisions about early intervention.”

The study was financed by a grant from the Internal Grant Agency of the Czech Republic.

The study report, “Higher Prevalence of Antibodies to Borrelia Burgdorferi in Psychiatric Patients Than in Healthy Subjects” is posted on the Web at http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org under the February issue. ▪

Am J Psychiatry 2002 159 297