Rep. Jim McDermott (D-Wash.), the only psychiatrist in Congress, takes no pleasure in his prophetic abilities. In 1994 he warned APA members and anyone else who would listen about the potential hazards of managed care and urged support for a single-payer system of financing health care.

McDermott told the audience at the William C. Menninger Memorial Convocation Lecture at APA’s annual meeting that year, “The wildfire of managed care competition is sweeping across the landscape of medical practice.” He also quoted health care economist Uwe Reinhardt, who had predicted that in five years all doctors would be “serfs of the insurance industry.”

Earlier that year, McDermott, the only psychiatrist in Congress, urged APA’s Board of Trustees to support single-payer legislation, arguing, “[I]t is the only way you are going to have any chance in the future to have a say about health policy.”

In a recent interview with Psychiatric News, he discussed the political and economic factors that affect the current debate about health care reform and his single-payer legislative proposal.

“Everywhere you turn, there is another problem,” McDermott said. “The same tide that led to managed care in the early 1990s is building.”

The number of people without health insurance is increasing, as is the cost of health care. Now, however, little or no hope remains that managed care can solve the fiscal and access problems of the health care system.

“Our ability to deal with access problems is limited because there is no real health care system,” he said.

As in the 1990s, health care reform has become an important political issue. According to an analysis in the September 30 New York Times, “[As] the plight of the uninsured becomes more of a middle-class issue, . . . it is more politically potent.”

According to a September Gallup poll, 43 percent of Americans cited a candidate’s position on health care as “extremely important,” ranking just below terrorism and the economy.

With the failure of managed care to reform the health care system, there appears to be increasing receptivity to proposals for a single-payer system of financing care.

An ABC News-Washington Post poll released in late October found that by a margin of 62 percent to 32 percent the public favors a “universal health insurance program, in which everyone is covered under a program like Medicare that’s run by the government and financed by the taxpayers,” as opposed to the “current health insurance system, in which people get their health insurance from private employers, but some people have no insurance.”

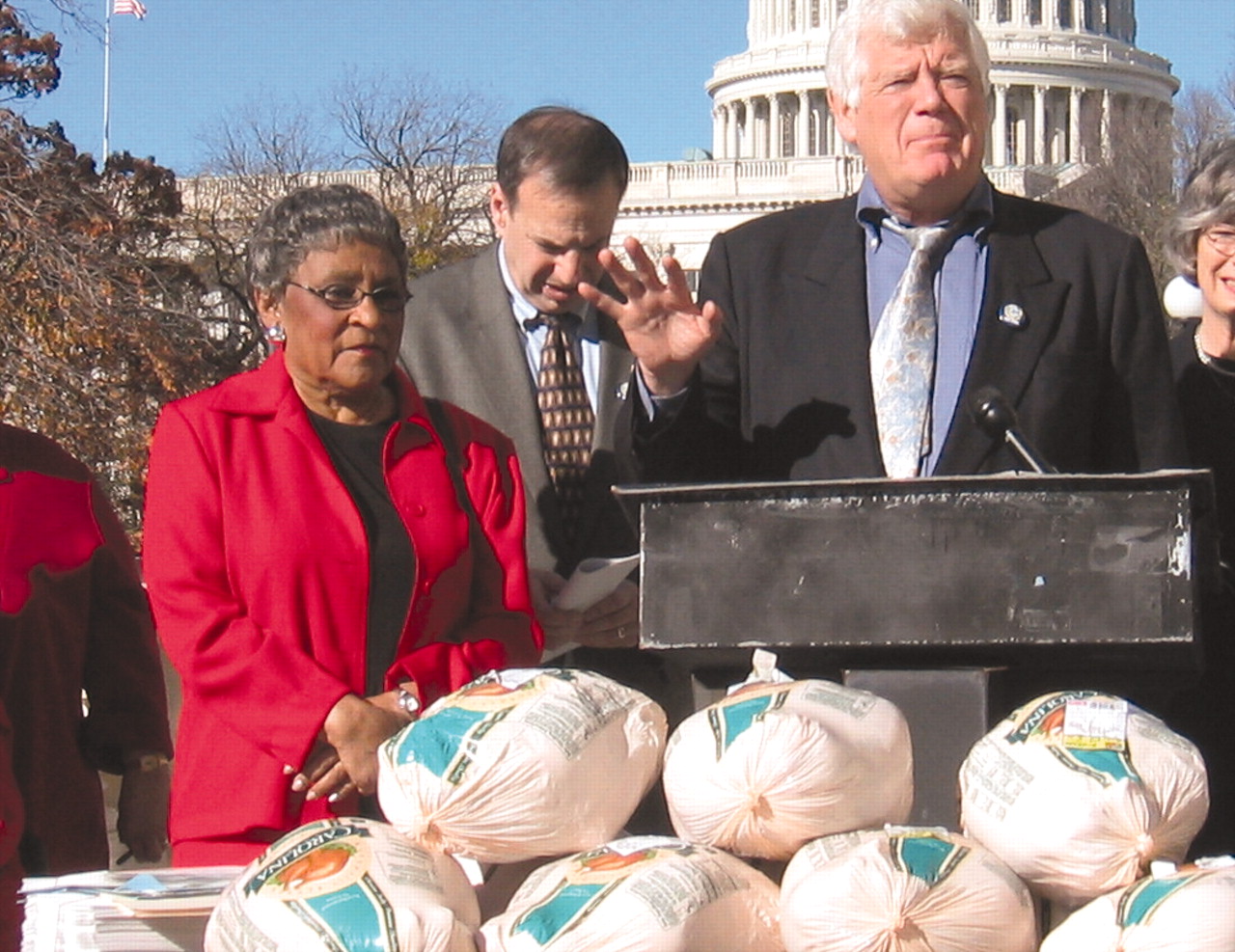

That change is welcome news to McDermott, who introduced the American Health Security Act (HR 1200) last March. The bill, which has 40 cosponsors, would establish a national and universal health program that would be funded by the federal government and administered by the states (Psychiatric News, October 3).

McDermott looked back to the 1960s when asked to consider the bill’s chances of passage. He said proposals for what would become the Medicare program had been “kicked around for a long time,” but had been defeated by forces that included strong opposition from the AMA and health insurance carriers.

But ultimately, in 1965, McDermott said, pressure on politicians from constituents became too great to resist, and the legislation was passed.

McDermott voted against the Medicare legislation that passed the House of Representatives on November 22, charging that its “real goal” is to privatize Medicare (see

page 2).

He added, “The bill is designed to protect and increase drug companies’ and insurance companies’ profits. The pharmaceutical industry will reap about $140 billion in profits if this becomes law. The bill explicitly prohibits the secretary of Health and Human Services from negotiating lower drug prices on behalf of America’s 40 million Medicare beneficiaries.”

McDermott cited stigma and ignorance as factors that have prevented passage of federal legislation promoting parity in benefits for mental illness with those for other forms of illness.

“The idea that one must pull oneself up by the bootstraps still has a lot of power,” he said. Unless people have had direct contact with mental illness, they often do not understand that it is a chronic, but treatable disease.

“Get to know your local politicians. Become active in the community in visible ways,” McDermott urged APA members. “Education about mental illness must be a constant process.”

He praised the work of APA in helping to establish the Mental Health Caucus in the House of Representatives, which has worked to provide that education. ▪