A desktop computer was not even a remote possibility when John Talbott, M.D., became editor of Psychiatric Services in 1981.

He began to fill a shoebox with index cards that listed submitted manuscripts— a system that was an advance on that of his predecessor, Donald Hammersley, M.D., who kept the names on slips of paper.

In fact, the journal had not yet become Psychiatric Services. It was then called Hospital and Community Psychiatry, which was a change from its first name, Mental Hospitals.

Talbott told Psychiatric News that his aim was to make the publication “more academically rigorous without losing focus.”

“It was intended for clinicians in the trenches,” he said.“ We wanted to retain its practicality, but bring more research to bear on practice.”

Talbott immediately instituted a system of peer review for manuscripts and began the custom of including columns about various subject areas.

The first of these columns, on psychiatry and the law, continues today with its original editor, former APA president Paul Appelbaum, M.D.

Appelbaum told Psychiatric News that the idea of adding columns was only one example of the kind of energy and creativity Talbott brought to his new position.

He said, “APA publishes the American Journal of Psychiatry, so there had always been a question about the role of what was then Hospital and Community Psychiatry.”

Talbott more clearly defined the publication's target audience during his tenure, said Appelbaum, and turned it into the “premier journal for mental health services,” because of the diversity, quality, and time-liness of its articles.

APA President-elect Steven Sharfstein, M.D., a member of the journal's editorial board, said, “John, as APA's president and then as editor, brought the issues of public psychiatry to the forefront of the field—deinstitutionalization, care in the community, treatment of schizophrenia. From science to public policy, the journal became the resource for the clinician and administrator in the fight for resources and attention.”

Talbott said that when he became editor, the field of health services research was just beginning to develop.

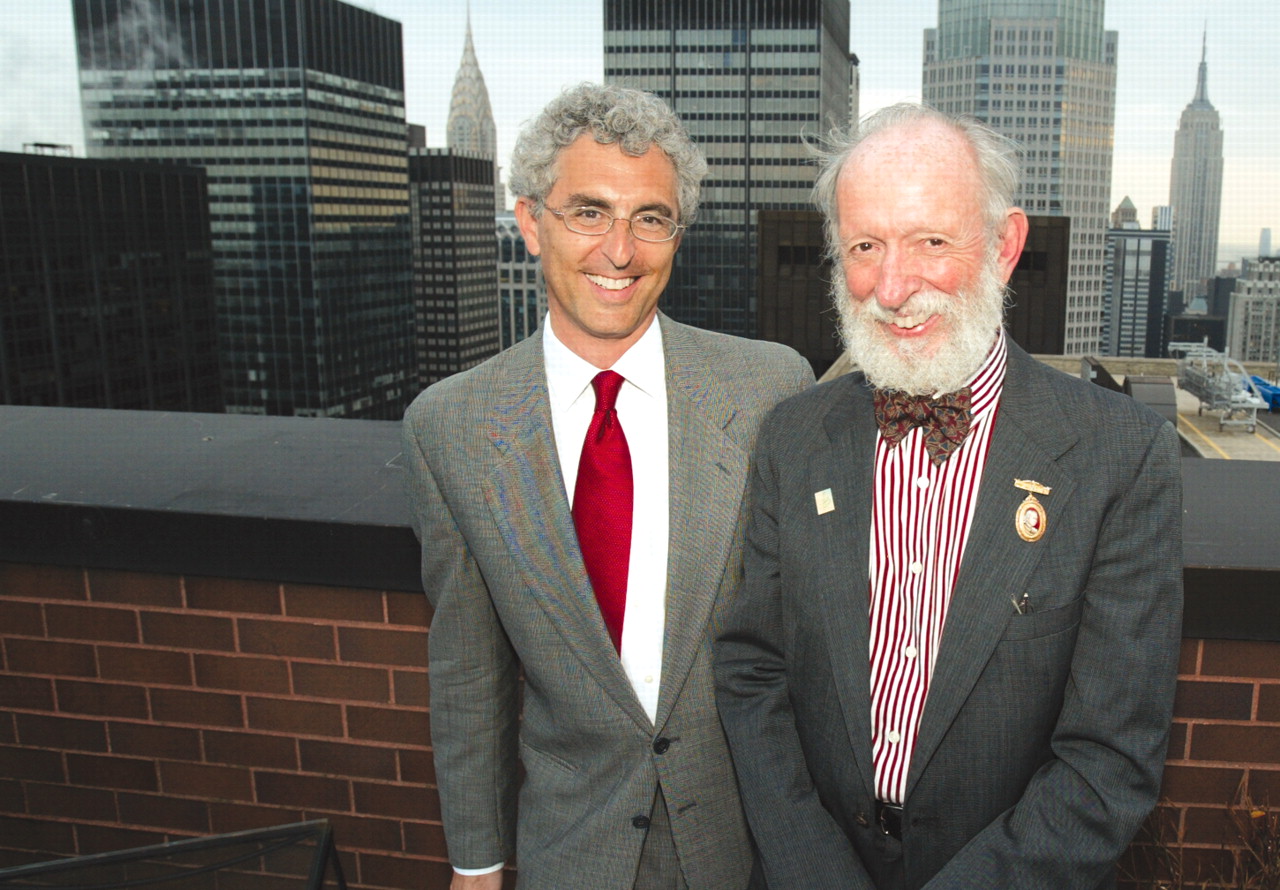

Howard Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., the incoming editor of Psychiatric Services, was an early proponent of that effort and the lead author of a paper, “Defining and Counting the Chronically Mentally Ill,” in the first issue under Talbott's editorship.

Goldman said, “John offered the journal as a place to publish findings from the developing field of mental health services research and economics. He published special sections on prospective payment and DRGs, the results of the evaluation of various service-demonstration programs, co-occurring disorders, homelessness and mental illness, health care reform, and evidence-based practices.”

Robert Rosenheck, M.D., a recipient of APA's Senior Scholar Award in Health Services Research in 2000 and also a member of the editorial board, published much of his early health services research in the journal.

He said, “I remember often wondering about a paper I was writing, `What's John going to think about this?' He was an omnipresent guiding light in the development of the field.”

Rosenheck is director of the Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System.

Talbott cited research about the VA's population and mental health services as an important area that needed visibility when he began his work as editor.

Rosenheck said, “John, in addition to supporting the VA's research activities, was a great help in the development of the agency's community-based services. He helped design the first trial of ACT [Assertive Community Treatment] in the VA. After that trial showed success, his congressional testimony provided a major impetus for wider dissemination of the model.”

Appelbaum also credits Talbott with a keen ability to recognize important trends in the “changing landscape of mental health.”

In 1981 Congress had just passed the Mental Health Systems Act, the primary legislative result of the report of President Jimmy Carter's Commission on Mental Health.

Problems were surfacing, however, at community mental health centers, and the fallout from deinstitutionalization of psychiatric patients had been apparent for some time. Managed care was on the horizon.

“John saw that the boundaries between the public and private sectors were blurring. He knew it was necessary to focus on psychiatric services as a whole, not on the venue in which they were offered.”

From the beginning, Talbott had enlisted experts in specific areas of mental health to help him sort out the rapid changes in the field. He also realized that Psychiatric Services had to limit itself to those topics it could cover well.

“The field of genetics changes so fast there was no way we could keep up with it,” Talbott said. And, he added, “There are topics like the impact of Medicaid budget cuts in Oregon that are done better by the New York Times.”

Psychiatric Services now has a circulation of 24,000 and boasts a growing international audience. One in 10 of its submissions comes from a country other than the United States.

Goldman said, “With the assistance of our outstanding editorial board and staff, I hope to build on John's remarkable legacy, improving the scientific rigor of Psychiatric Services, while maintaining its relevance and readability.” ▪