Under the frequent—and often hyperbolic—headlines in major newspapers throughout the United States, the debate on whether SSRIs really cause children and adolescents to become suicidal has boiled down to a critical realization: Physicians now face a crisis of confidence in the American-bred system that conducts clinical research and, it would seem, publishes only the most marketable results.,

Physicians in the trenches are beginning to wonder what exactly they really know— or perhaps don't know—about the drugs they are prescribing and how that knowledge base affects what is written on the prescriptions that bear their signatures.

Many of the concerns raised recently have been heard before. In this last year, however, they have risen to a level that seriously challenges physicians' comfort level with prescription drugs. Particularly disconcerting are new allegations that question the integrity of not only the scientific evidence base, but also the system that produces the data and the researchers who analyze it.

In April the British Medical Journal published a paper by Jon Jureidini, M.D., head of the department of psychological medicine at Women's and Children's Hospital in North Adelaide, Australia, and colleagues. The article reviewed the evidence base for efficacy and safety of antidepressants in children and adolescents. The authors included in their review published clinical trials, as well as some unpublished data made public by the U.K. Committee on Safety of Medicines. At best, Jureidini's conclusions were direct and to the point, but by some people's estimation the conclusions seemed inflammatory, with abundant references to the individuals who led the research or wrote the articles, rather than to the research methods, data analysis, or conclusions.

“In discussing their own data, the authors of all of the four larger studies have exaggerated the benefits, downplayed the harms, or both,” Jureidini and his coauthors wrote.

“Improvement in control groups is strong; additional benefit from drugs is of doubtful clinical significance,” they said, adding,“ adverse effects have been down-played.” They concluded that“ antidepressant drugs cannot confidently be recommended as a treatment option for childhood depression.”

Jureidini and his coauthors pointed out that “accurate trial reports are a foundation of good medical care. It is vital that authors, reviewers, and editors ensure that published interpretations of data are more reasonable and balanced than is the case in the industry-dominated literature on childhood antidepressants.”

Jureidini listed a “competing interest” with the BMJ study, noting he is the chair of Healthy Skepticism, an international lobbying organization based in Australia whose goal is “improving health by reducing harm from inappropriate, misleading, or unethical marketing of health products or services, especially misleading pharmaceutical promotion.”

So, it was a bit unusual that an article in a major peer-reviewed publication appeared to be directly questioning the very integrity of the researchers who had overseen clinical antidepressant trials. Many researchers interviewed for this article saw it as an unusually personal attack.

The researchers who took the brunt of the apparent attack were the principal investigators and lead authors of the trials in question: Graham Emslie, M.D., the Charles E. and Sarah M. Seay Chair in Child Psychiatry and professor of psychiatry in the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas; Martin Keller, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University; and Karen Dineen Wagner, M.D., Ph.D., the Clarence Ross Miller Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and director of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston

Emslie was the principal investigator on the fluoxetine (Prozac) pediatric trials; Keller oversaw pediatric clinical trials of paroxetine (Paxil); and Wagner was the principal investigator on two sertraline (Zoloft) pediatric clinical trials.

Two weeks after the BMJ article, Lancet published a systematic review of SSRIs for childhood depression that also compared published and unpublished data from the same clinical trials that Jureidini analyzed.

Picking Through the Data

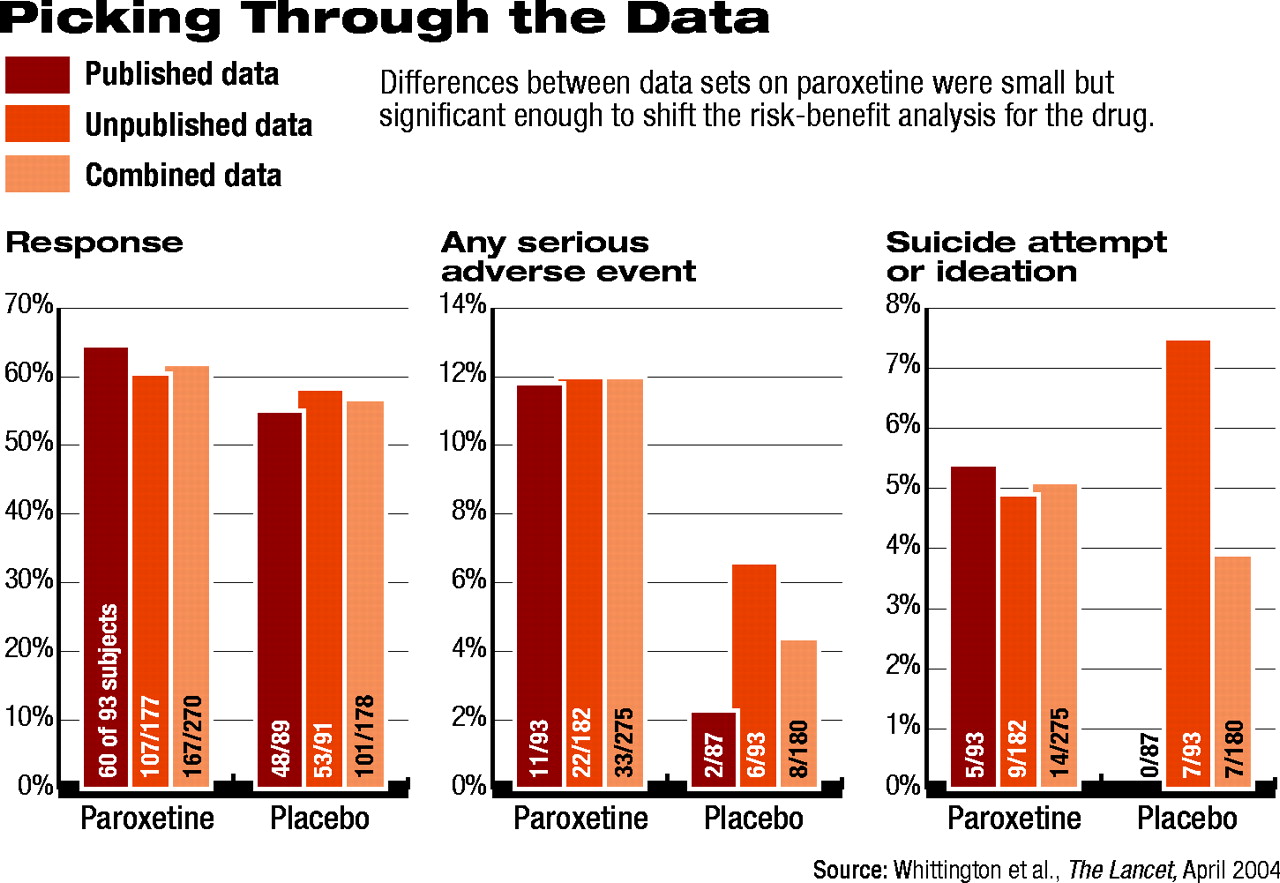

Tim Kendall, M.D., deputy director of the Royal College of Psychiatry's Research Unit in London and co-author on the Lancet article, talked with Psychiatric News about the group's findings. Kendall explained that for each antidepressant medication, the group analyzed published clinical trial data separately from unpublished data from U.K. regulatory authorities and found discrepancies.

“From the published data, we thought we might have recommended some of these drugs,” Kendall said. “In other words, the risk-benefit profile, in the main, was favorable—not massively so, but at least modestly so.” Then, he said, “we looked at the unpublished data, and they clearly were not favorable.”

For example, Kendall said, the response data for paroxetine looked better than for placebo, though the difference was only modest (see chart). With regard to adverse events, even in the published data, there “was clearly a problem with the drug.”

When the group analyzed the unpublished data, the findings shifted. For example, response rates were significantly lower for paroxetine, and the placebo effect was even more pronounced than it was in the published data. This effectively narrowed the difference between the two groups, voiding the statistical significance. In addition, the adverse-event picture, including the data on suicidal behavior, looked more troubling.

When the researchers analyzed the published and unpublished data together, the SSRI no longer held a reasonable benefit for pediatric depression to justify the apparent risks.

There was not a “massive difference” between “the published stuff versus the unpublished,” Kendall said, “but [the profile] certainly switches from a favorable riskbenefit profile to an unfavorable one.” And with each of the SSRIs the researchers examined, they found the same trend: the published data were significantly more favorable than the data that had not been peer reviewed.

Defining Context

Neither Keller nor Wagner responded to multiple requests for interviews for this article; however, Emslie agreed to an extended phone interview.

“Apart from the first Prozac trial and one of the Paxil trials, all the rest of the data [in question] arise from an act of Congress, not from the industry wanting to do these studies,” Emslie told Psychiatric News.

Indeed, the data on SSRI use in children largely resulted from Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requests to drug manufacturers issued through the old “Pediatric Rule”—a regulation born from the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA). However, FDAMA did not require that studies be carried out and provided little if any penalty for a company not agreeing to the FDA's request. In essence, the Pediatric Rule gave companies' an additional six months of patent protection for conducting minimal research to collect data on safety of a medication in pediatric populations. Under the Rule, the FDA requested pediatric data from manufacturers of the 100 top-selling medications in the U.S.

Drug companies were slow to undertake pediatric research, and the FDA's legal authority to mandate pediatric clinical trials was challenged. Finally, the Pediatric Rule was given the weight of law under The Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003 (PREA) which left in place patent extension but further defined the FDA's legal authority to mandate studies. In addition, PREA required pediatric studies as part of every application for approval of every drug—with few exceptions—retroactive to include all applications submitted since January 1, 1999.

However, between the Pediatric Rule and PREA, the FDA began receiving pediatric data that did not live up to the expectations of either Congress or the FDA.

“Many of the companies simply threw together the quickest, cheapest, easiest, clinical trial of their drug in kids they possibly could,” said one government official, a senior researcher who is familiar with the situation and agreed to comment if not named.

“The companies pretty much knew from the outset that they wouldn't get a full pediatric indication, and the Pediatric Rule [initially] didn't really have any stipulations that the data had to be good or the methods solid. The rule simply said if they submitted some data, they'd get their patent extended. And that, simply, translated into dollars,” the official explained.

Indeed, in many cases, the Pediatric Rule was directly responsible for hundreds of millions of dollars in additional sales of a branded product over the six-month extension.

The official continued, “Data collection in these studies was sloppy, recruitment was sloppy, the statistics and methods were manipulated, and, of course, only the positive studies were submitted. Why would a drug company put out data that are negative? That would amount to commercial suicide. But what can you expect, really? Garbage in, garbage out.”

Emslie agreed in part. “Getting all the positive as well as the negative data” is an issue, he said. But this is true for many different classes of medications,” not just antidepressants, he said (see box).

Wanted: All Relevant Data

The PREA was intended to ensure that the FDA was given all the appropriate pediatric data, both positive and negative, on a product so that an initial approval decision could be made on the whole data set, not just the most marketable data set.

The law includes language mandating that for any application to the FDA for a “new active ingredient, new indication, new dosage form, new dosing regimen, or new route of administration,” the application must include“ data, gathered using appropriate formulations for each age group... to assess the safety and effectiveness of the drug or the biological product for the claimed indications in all relevant pediatric subpopulations [and data to] support dosing and administration for each pediatric subpopulation for which the drug or biological product is safe and effective.”

If a drug maker fails to submit all of the data, the drug could be declared“ misbranded solely because of that failure and subject to relevant enforcement action.”

Yet the FDA acknowledges that even today—a year and a half after the PREA went into effect—the agency isn't sure whether it has all the data it's supposed to have on the medications submitted under PREA's requirements.

“I'm not aware of any standard mechanism in place for assuring that all pertinent data have been submitted,” Thomas Laughren, M.D., medical team leader of the FDA's Neuropharmacological Drug Products division, told Psychiatric News. “It depends mostly on the review team being aware of what has been done.”

Nonetheless, Laughren was not aware of any instance in which a company was found to have purposefully withheld data from the agency.

In response to Laughren's comments, the government official who asked not to be named said, “It is not only possible that the FDA does not have all the data, it is highly probable.”

Yet, Psychiatric News discovered that even if the FDA possesses all of the relevant data on a particular product, that data may not be easily accessible to the medical community, researchers, the media, or the public.

“Data become available only after an approval action,” Laughren said, “and then only data that clinical and statistical reviewers [at the FDA] decide to include in their reviews [become part of the drug approval package]. The original data sets are proprietary and never available unless a sponsor decides to release them.”

The FDA has attempted with some success to increase access to the information by posting a large amount of summary data on its Web site under an“ Approvals” section.

If someone is looking for data not posted on the FDA's Web site, the person must file a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. Over the last year, in the course of this ongoing investigative report, Psychiatric News filed FOIA requests for “all approval package documents [and] their attachments and appendices” for each of the antidepressant medications being questioned. To date, a large amount of data has been received in response to those requests.

Over the last several months, several SSRI manufacturers have been accused in the media of attempting to “bury or hide” negative study data. The increasingly heated issue led the AMA, at the request of APA and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, to advocate for a mandatory, federally administrated, clinical trials registry (see page 1). Separately, a large group of medical journal editors called for the same thing.

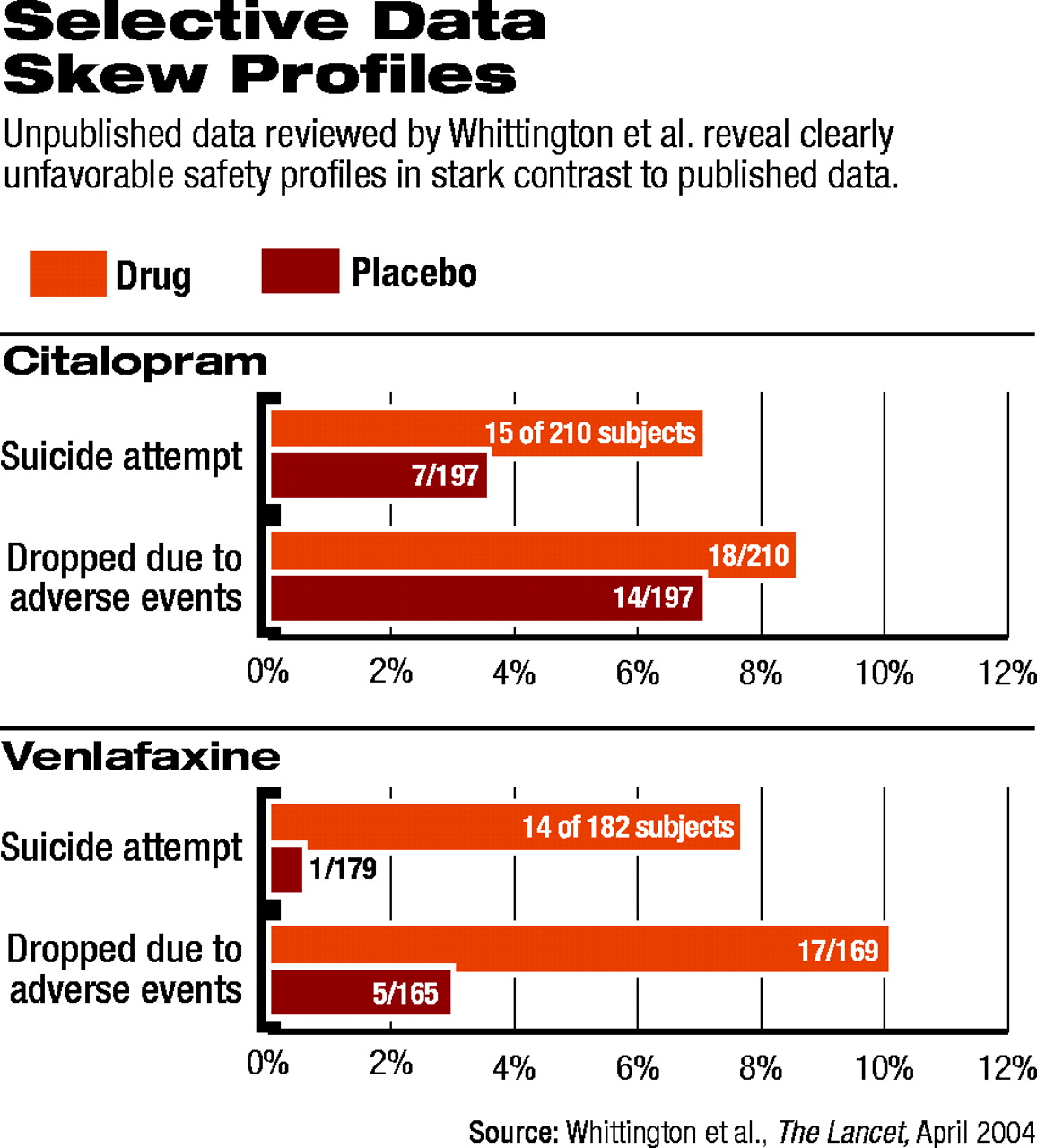

In the meantime, GlaxoSmithKline announced it would create its own registry and publicly post it on its Web site. At the same time the company posted summary data from all of its pediatric paroxetine studies, the majority of which had never been made public. Shortly thereafter, Merck announced it would support such a clinical trials register, and Forest Labs released pediatric data on both citalopram and escitalopram. In Washington, D.C., several senators and representatives called for legislation establishing a mandatory registry for all clinical research, even though FDAMA already contains an obscure requirement that all trials be registered.

Comparing Apples and Oranges

The most significant issue facing regulators and researchers in attempting to analyze the safety and effectiveness of SSRIs in pediatric populations is the extreme variability between and within the studies (see chart on page 1).

“First of all, some of these [pediatric antidepressant] studies were conducted in Europe, some in America,” Arif Khan, M.D., pointed out. Khan is medical director at the Northwest Clinical Research Center in-Ballevue, Wash., and was involved in conducting or reviewing many of the studies now in question. “The conduct of American trials by American psychiatrists is a situation that is entirely different from European trials conducted by psychiatrists there.”

Some differences in these studies, Khan told Psychiatric News, include differences in the studies' methodology, populations, and data assessment, and may not be directly comparable.

“Some of the European studies had an overabundance of adolescent girls in the drug groups versus the placebo groups,” Khan said as an example. “The randomization wasn't even.”

Emslie echoed this same point, adding that he suspects that most subjects in the European trials had mild to moderate depression, rather than severe depression. Significant evidence in adult populations indicates that SSRIs are not very effective for mild to moderate adult depression. Thus, Emslie asked,“ why would they work for mild or moderate depression in kids?”

In addition, many methodological differences exist among the studies in the number of sites used and the number of researchers involved, the protocols for assessment and randomization into the study, and the statistical analyses of the resulting data.

“You have an extremely heterogeneous group of trials using differing definitions and assessments on differing study populations and different analyses,” Khan said. “So obviously any comparisons are going to be questionable.”

Experts consulted by Psychiatric News agreed that meta-analyses and overall reviews of the two dozen or so pediatric antidepressant clinical trials may never reach any reliable conclusions about efficacy and safety of SSRIs in pediatric populations.

“The FDA and the Columbia University group may not come up with any solid answers,” Khan suggested, referring to the group of suicidality experts contracted by the FDA to reanalyze the SSRIs' adverse-effect profiles.“ What you see is that this suicidal behavior in the placebo group runs anywhere from 0.6 percent to just under 5 percent. In the drug groups it runs from a low of just under 3 percent to a high of 8 percent. There's a lot of variability, but in general the pattern holds true. There is a fairly clear trend in increased risk in the drug groups versus the placebo groups, regardless of which drug you are looking at.”

Common Ground Sought

That trend does have one exception: fluoxetine. It is the only antidepressant whose data were strong enough to have won FDA approval for the treatment of pediatric depression. Most of the experts interviewed for this article, including Khan and Kendall, agreed that the published and unpublished data on fluoxetine's effectiveness and safety in children and adolescents show that the drug provides significant clinical improvement and has not been as closely associated with the harmful and suicidal behaviors of other SSRIs in children.

Emslie—“the father of pediatric Prozac”—can't be sure why fluoxetine is different from the other SSRIs.

“First of all, with respect to efficacy, you have to ask whether or not it really is any better than the other SSRIs,” Emslie said.“ But no controlled head-to-head studies have been done in children and adolescents. So it could be methodological differences. We did those studies early on [in the evolution of SSRI pediatric clinical trials], and maybe we did something better with respect to study population or had better quality sites with better investigators. As far as safety is concerned, it may be that the drug is better tolerated on some level, and I certainly think that dosing is probably easier with fluoxetine.”

The FDA expects to schedule a second advisory committee meeting on the issue as soon as it receives the reanalysis from the Columbia University group. The report had been expected in early July, but as this article went to press, neither the agency nor the university indicated that the release of the report was imminent.

So for those clinicians who continue to question their confidence in SSRI prescriptions for children and adolescents, there is no immediate resolution in sight.

“We really don't know anything different today than we did five years ago,” Khan said. “What we have is a mixture of trial results that generally favor the active drug. The trials certainly do not favor placebo, and it is important that that is understood. Failed trials don't necessarily mean that a drug does not work.”

Emslie echoed Khan's statement, adding that “it's really a question of how do these clinical trials inform us about clinical guidelines for care. I think they inform us that generally the SSRIs are probably effective— the data are largely ambiguous, but certainly not negative. But every medication [requires] a risk-benefit analysis.”

Khan added, “As long as the patient and the clinician understand what the risk profile is, I think it is very appropriate to prescribe [SSRIs].”

The individuals interviewed by Psychiatric News agreed on at least one point: “We've really got to get this right,” Kendall said.“ The whole clinical and scientific community, as well as regulators and the public, need to be involved in assuring that we do get it right. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

An abstract of theLancetarticle,“ Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Childhood Depression: Systematic Review of Published Versus Unpublished Data,” is posted online at<www.thelancet.com/journal/vol363/iss9418/abs/llan.363.9418.original_research.29377.1>. TheBMJarticle, “Efficacy and Safety of Antidepressants for Children and Adolescents,” is posted at<http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/328/7444/879>.▪

BMJ 2004 328 879