Societal attitudes toward people with mental illness have long been characterized by stigma, which may prevent people with mental health problems from seeking treatment and hinder the progress of legislation to increase access to care.

But the results of a new survey suggest that at least some Americans do not discriminate against people with mental illness, have at least a basic understanding of the nature of mental disorders, and would pay higher taxes to improve access to mental health services.

According to a survey of 650 Houston-area residents conducted last spring by the Center for Public Policy at the University of Houston, 63 percent believe mental illness is primarily due to a brain disorder, while just 5 percent believe it is due to a character flaw.

The remainder of respondents attributed mental illness to “something else,” including a genetic disorder (10 percent), the person's home environment (9 percent), a chemical imbalance (5 percent), or stress (5 percent), among other variables.

In addition, 86 percent of people surveyed said they believed that health insurance companies should be required to cover mental health treatment in the same way they do other illnesses.

“This study is a powerful indication of an evolutionary process in which the stigma that has been traditionally attached to mental illness is gradually disappearing,” said Stephen Klineberg, Ph.D., director of the annual Houston Area Survey and a professor of sociology at Rice University.

The Houston Area Survey has been conducted since 1982 using a sample of Houston-area residents who are said to be representative of the U.S. population and who are selected through a two-stage, random-digit-dialing procedure.

Each year the survey gathers information on beliefs and attitudes of residents on controversial issues, such as abortion and civil rights for gays and lesbians, and other topics on the country's agenda.

This year, the Mental Health Association of Greater Houston contracted with Rice University to incorporate six questions about mental illness in the survey.

The researchers found the following:

•

51 percent of respondents said they would be willing to pay higher taxes to improve access to mental health services in the Houston area.

•

56 percent of respondents believed that most people being treated for a mental illness are able to live a normal life.

•

When asked, “How concerned would you be if you discovered that a person being treated for a mental illness was living in your neighborhood?,” 47 percent said they would not be concerned, 33 percent said they would be somewhat concerned, and 14 percent responded that they would be very concerned. The remainder of the respondents either didn't answer the question or indicated that they didn't know.

•

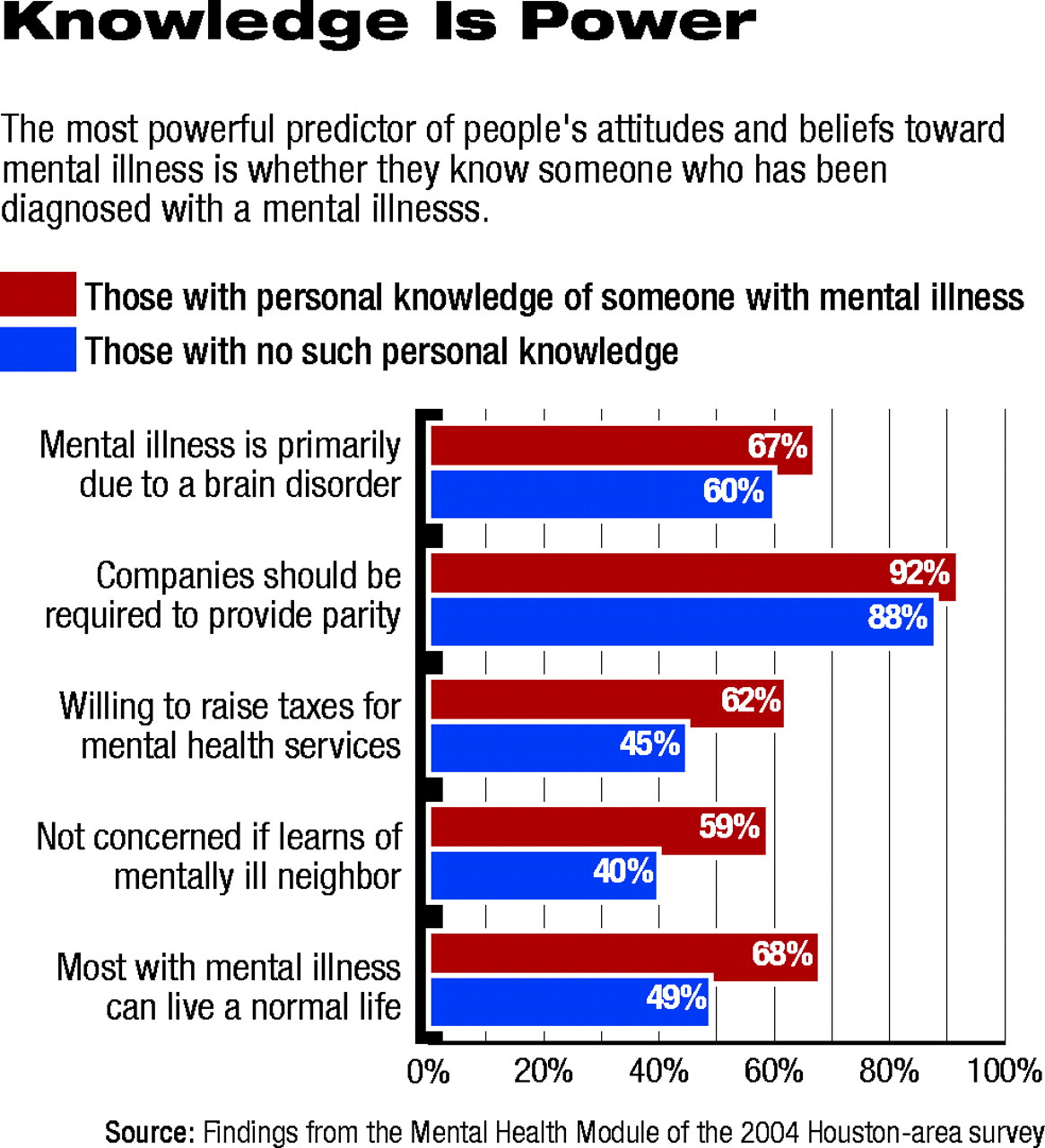

38 percent of respondents had a friend or family member who had been diagnosed with a mental illness.

Klineberg noted that if respondents knew a person with mental illness, they were much more likely to believe that mental illness is a brain-based disorder, that treatments work, and that a tax increase to support improved access to mental health services is a good idea.

He also collected information about each respondent's age, race, education, gender, and religion. None of those variables predicted responses to the questions about mental illness.

Jeremy Lazarus, M.D., chair of APA's Council on Advocacy and Public Policy and vice speaker of the AMA House of Delegates, said he was encouraged by the survey's findings.

“The fact that people say they would be willing to pay more taxes to fund mental health services is a hopeful sign.”

Yet the fact that parity legislation is stalled in the House of Representatives, Lazarus said, points to the fact that “stigma is still a problem, [as evidenced by] lawmakers' unwillingness to treat mental illnesses in the same way other illnesses are treated.”

The report, “Public Perceptions of Mental Illness: Findings From the Mental Health Module Included in the 2004 Houston Area Survey,” is posted online at<www.mhahouston.org>.▪