The release of the stage 1 results from the National Institute of Mental Health's Treatment of Adolescent Depression Study (TADS) could not have come at a more appropriate—or highly charged—time.

Right in the middle of a series of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) hearings, Congressional inquiries, and widespread debate over the use of antidepressants to treat youth with depression, the TADS results answer at least one key question.

“These results should really put to rest the debate over whether medication is effective in adolescents with major depression,” declared Peter Jensen, M.D., Ruane professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at Columbia University. “Fluoxetine clearly works in carefully selected, properly diagnosed teenagers with moderate to severe major depression.”

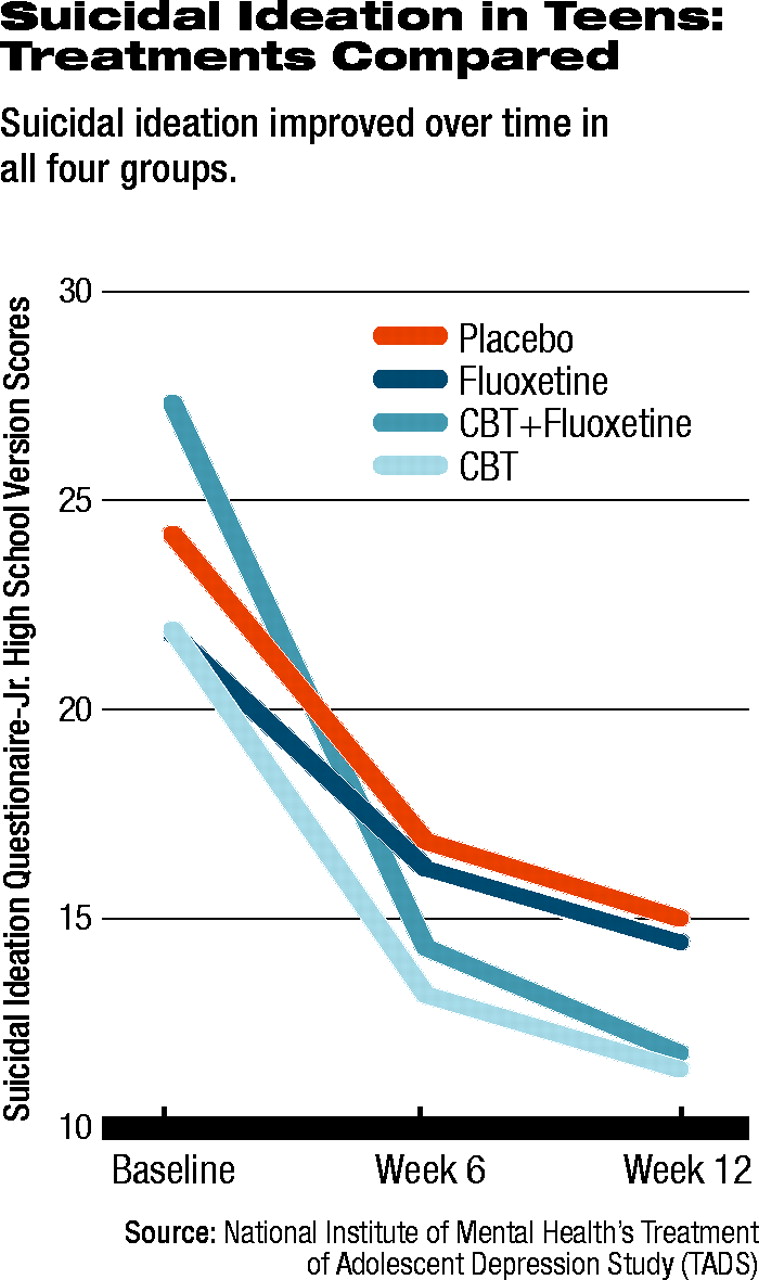

“It was noteworthy that suicide-related ideation and self-harm-related behaviors dropped dramatically in all groups, along with the substantial clinical benefits from getting effective treatment with medication, with or without CBT. Of course, this benefit of medication still doesn't rule out the possibility or rare but real adverse events in kids on meds. Even though penicillin can be be lifesaving in certain circumstances, some people have bad reactions to it, and doctors always need to be cautious and monitor the patient carefully, regardless of the medication. But we don't stop using penicillin because of rare adverse events; that would harm many more people.”

Jensen, director of the Center for the Advancement of Children's Mental Health at Columbia, was not a part of the TADS research team.

The TADS group was led by John March, M.D., professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine. March led a large group of researchers and clinicians at 13 academic centers across the country who studied 439 adolescents with major depression in the multiyear, multimillion-dollar project funded by NIMH.

The goal was to evaluate the effectiveness in a real-world setting of four specific treatments: cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), the SSRI fluoxetine (Prozac) alone, or the combination of both CBT and fluoxetine, all compared with a single control group that received a placebo pill. The CBT arms of the study involved a “skills-oriented treatment based on the assumption that depression is either caused by or maintained by depressive thought patterns and a lack of active, positively reinforcing behavior patterns.” Patients completed 15 CBT sessions of 50 to 60 minutes over the 12 weeks of the study. Patients on fluoxetine or placebo were monitored during six 20-minute to 30-minute sessions over the 12 weeks. A pharmacotherapist checked clinical status and medication effects and depending on clinical ratings was able to adjust doses of fluoxetine or placebo. In addition, patient education was provided including encouragement on the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for depression.

The study involved multiple stages. Stage 1 lasted 12 weeks and compared the four treatment groups' acute response. The results of stage 1 were reported in the August 18 Journal of the American Medical Association. Further reports from other stages will be reported in the future.

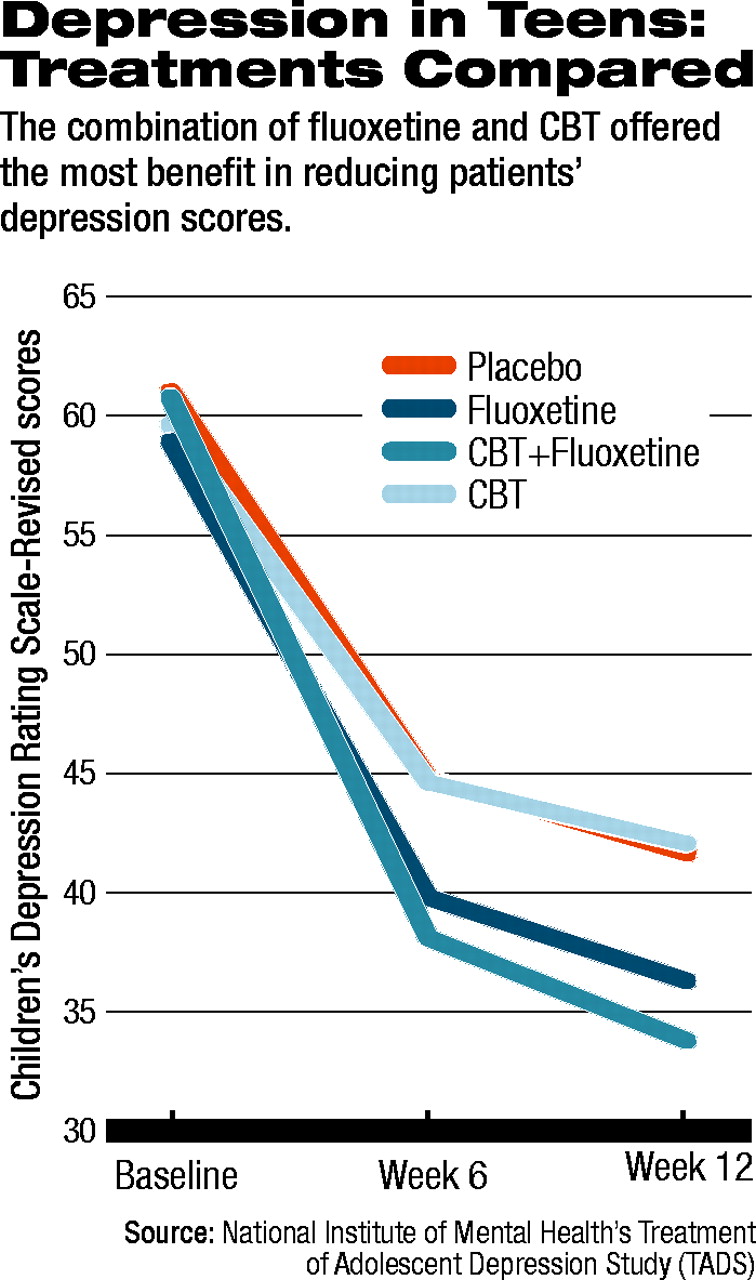

All 439 patients across the four treatment groups improved from baseline through six weeks and on to the 12-week assessment that closed stage 1. Two primary outcomes were chosen: scores on the Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R), at weeks six and 12, compared with baseline; and the 12-week rating on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI) scale. A CGI score of 1 (much improved) or 2 (very much improved) was defined as a“ response” to treatment.

Significantly, response rates varied widely between the four groups. Of the group receiving CBT/fluoxetine, 71 percent were rated at 12 weeks as responders. Among those taking fluoxetine alone, 60.6 percent responded. For those who received CBT alone the response rate was 43.3 percent. And for those receiving a pill placebo, the response rate was 34.8 percent.

Two things are significant about those numbers, noted Graham Emslie, M.D., the Charles E. and Sarah M. Seay Chair in Child Psychiatry and professor of psychiatry in the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, who was the principal investigator for TADS at Southwestern.

“It's unusual, first of all to see a placebo effect actually so relatively low,” Emslie said, adding, “it's also nice to then see such a good degree of separation between the active treatments and placebo.”

Emslie believes the results are at least in part attributable to the strength of the protocol's patient-selection criteria. At the time of entrance to the study, patients had to have been ill for at least six weeks without improvement. Another three weeks on average passed during assessment and patients being randomly assigned to their treatment group. After nine weeks of consistent depressive illness, the researchers thought it unlikely that patients would respond strongly to placebo.

Compared with placebo, CBT/fluoxetine was the strongest therapeutic approach, with improvement on the CDRS-R scores of patients on the combination being statistically significant. CBT/fluoxetine was also statistically significantly superior to either fluoxetine alone or CBT alone. Fluoxetine alone was superior to CBT alone as well; however, CBT was not statistically significantly different from placebo.

When the researchers examined patients' scores on the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ) -Jr. High School Version, an interesting trend appeared. At baseline, 29 percent of the total population in the study met criteria for clinically significant suicidal thinking. All four groups' scores on the SIQ improved (see table at left), with the CBT/fluoxetine group again showing the most improvement. However, the group receiving CBT alone had the second greatest improvement, followed by the fluoxetine group.

Both Jensen and Emslie pointed out that the data on harm-related and suicide-related adverse events during stage 1 indicate that the events were clustered in the groups that received fluoxetine, either alone or with CBT. The group receiving fluoxetine alone, however, was the highest in both the harm-related and suicide-related categories of serious events.

Patients receiving fluoxetine alone had the highest risk (calculated as an odds-ratio) of experiencing a harm-related event, compared with those receiving placebo. Patients in the CBT/fluoxetine group were less likely than those taking fluoxetine alone, but more likely than those receiving placebo to experience a harm-related event. Compared to placebo, those in the CBT alone group were slightly less likely to harm themselves or others compared to placebo.

However, because the actual numbers of patients in any of the four groups experiencing a harm-related event were small, the confidence intervals for the calculated odds ratios were quite wide, and none of the odds ratios statistically significant. Only when the researchers combined all patients taking an SSRI (those in the fluoxetine group plus those in the CBT/fluoxetine group) and compared those with all patients not getting any drug, did the odds ratio become significant. Those taking an SSRI were more likely to experience a harm-related event than those taking no drug (odds ratio 2.19, 95 percent confidence interval 1.03 to 4.62). In addition, when the researchers pooled all patients receiving CBT (with or without fluoxetine) and compared them with all patients not receiving CBT (placebo plus fluoxetine groups), again those receiving CBT appeared to be less likely to experience a harm-related event, though this result also was not statistically significant.

A similar pattern emerged with the same comparisons for suicide-related events; however, none of the suicide-related event odds ratios reached statistical significance.

“CBT appeared to be exerting some sort of protective effect, whereas fluoxetine appeared to be associated with harm-related and suicide-related events,” Emslie pointed out. Seven of the 439 patients attempted suicide during the trial, six of which were in either the fluoxetine-plus-CBT or the fluoxetine-alone group, while one was in the placebo group. “There certainly looks like there is something there, but what exactly it is, I don't think we understand yet. But fluoxetine is probably not alone. We need to figure out what other medications might display this same pattern. Interestingly, looking even closer,” Emslie continued, “there was a stepwise increase in suicide-related events along with increasing response. It could be that the old theory of improved energy and activation actually is tied to increased risk. But it is still only a theory.”

What is clear is that all patients must be monitored closely, both Jensen and Emslie stressed. “You can't just write a prescription and send them on their way. That is clearly not the best practice,” Jensen said.“ Careful diagnosis plus careful assessment then should always lead to careful selection of medication—preferably along with some therapy—and close monitoring.”

JAMA 2004 292 807