Expressing personal or collective trauma through poetry, creative writing, or the visual arts communicates the subjective experiences of the survivor.

“The writer tries to make sense of the trauma and speak for others who cannot, or at least not as eloquently. The reader gains new insights into the traumatic experience and becomes empathetic towards the survivor,” said Reginald Gibbons, professor of English at Northwestern University and publisher of several poetry collections and books. Gibbons spoke at a symposium on “Turning Trauma and Recovery Into Art” at the recent meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) in Chicago. The symposium was co-sponsored by the University of Illinois at Chicago International Center on Human Responses to Social Catastrophes, which is directed by psychiatrist Stevan Weine, M.D.

“First-person narratives of trauma in literature connect the reader to the individual’s life. The words grab the reader by the heart in sharp contrast to reading clinical cases,” said Migael Scherer, author of several books and another symposium speaker.

When Scherer was raped 15 years ago, it was important to her to continue to write. She chronicled her struggle to recover in a journal titled Still Loved by the Sun, published by Simon and Schuster in 1992.

Scherer, who is the Dart Award director at the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma in Seattle, told Psychiatric News, “I wrote in a journal to try to explain things to myself rather than create a literary work. A friend to whom I showed some of my entries thought it might benefit others as well, so that’s how Still Loved by the Sun came to be published.”

Now They Understand

Many readers wrote Scherer about their reactions to the book. “Survivors of rape said that I expressed what they felt. People with relatives who had been raped said they now understood why life was so hard for them,” said Scherer.

Three other published books resulted from her sailing adventures. Scherer read the following excerpt from the chapter “Repairs” in her book Back Under Sail: Recovering the Spirit of Adventure (Milkweed Editions, 2003) at the ISTSS meeting (reprinted with permission).

Taking a proper bath requires a suspension of rushing about and gotta-do-it. It requires patience, and for me at least, a strange discipline to lie in the water and do nothing.

Then, No! and I sat up, gasping. My mind raced, backward then forward then backward again, imagining someone—a man—on the other side of the door, waiting. I saw the flimsy latch, the rotted door frame, the open window, and bare, dirty floor that was suddenly that other floor. I was caught, exposed, and helpless, my nerves on the outside of my skin, as if I were flayed.

A whimper, the beginnings of a sob; I held my breath and listened, forcing myself to focus on what was around me rather than the clamor inside.

I opened my eyes and looked hard, clawing myself up to the present. “I’m here,” I said to the unstoppable stream. “He’s there.” I made myself think of the rapist locked up, monitored, guarded, watched.

Poetry From Prison

Political activist and poet Dennis Brutus got to know Nelson Mandela in a South African prison in the 1960s.

At the time, nonwhites were excluded from professional sports in South Africa and Rhodesia, which meant they were excluded from participation in Olympic Games. Brutus, who opposed the exclusion, persuaded the Olympic Committee to finally expel those countries’ teams in 1970.

In the meantime, the South African government had barred Brutus from engaging in political campaigns. He was arrested for violating that ban when he tried to leave the country to attend an Olympic meeting in Europe in 1963. He was sentenced to 18 months of hard labor on the infamous Robben Island off Cape Town on South Africa’s coast, where Mandela was also held prisoner.

Poetry writing was prohibited in prison, but letters were allowed, so Brutus wrote several poems in his letters to his sister-in-law Martha that later were published.

He explained in an interview with Psychiatric News, “I knew my brother, who was also a political activist, would be sent to Robben Island soon. I shared my experiences there with Martha so she knew what life as a prisoner would be like for my brother. I believed that hearing about the conditions from me was better than the imagined terror.”

He read from Letters to Martha and Other Poems From a South African Prison (Poetry, Heinemann Educational Books, 1967) at the meeting.

Knowing your grief and anxious fears,

I send you these bits to fill the mosaic

Of your calm patient knowledge.

Picking jagged bits embedded in my own mind

So I can wrench some ease for my mind. . . .

Brutus eventually settled in the United States after being awarded political refugee status. He is a professor emeritus of Africana studies at the University of Pittsburgh.

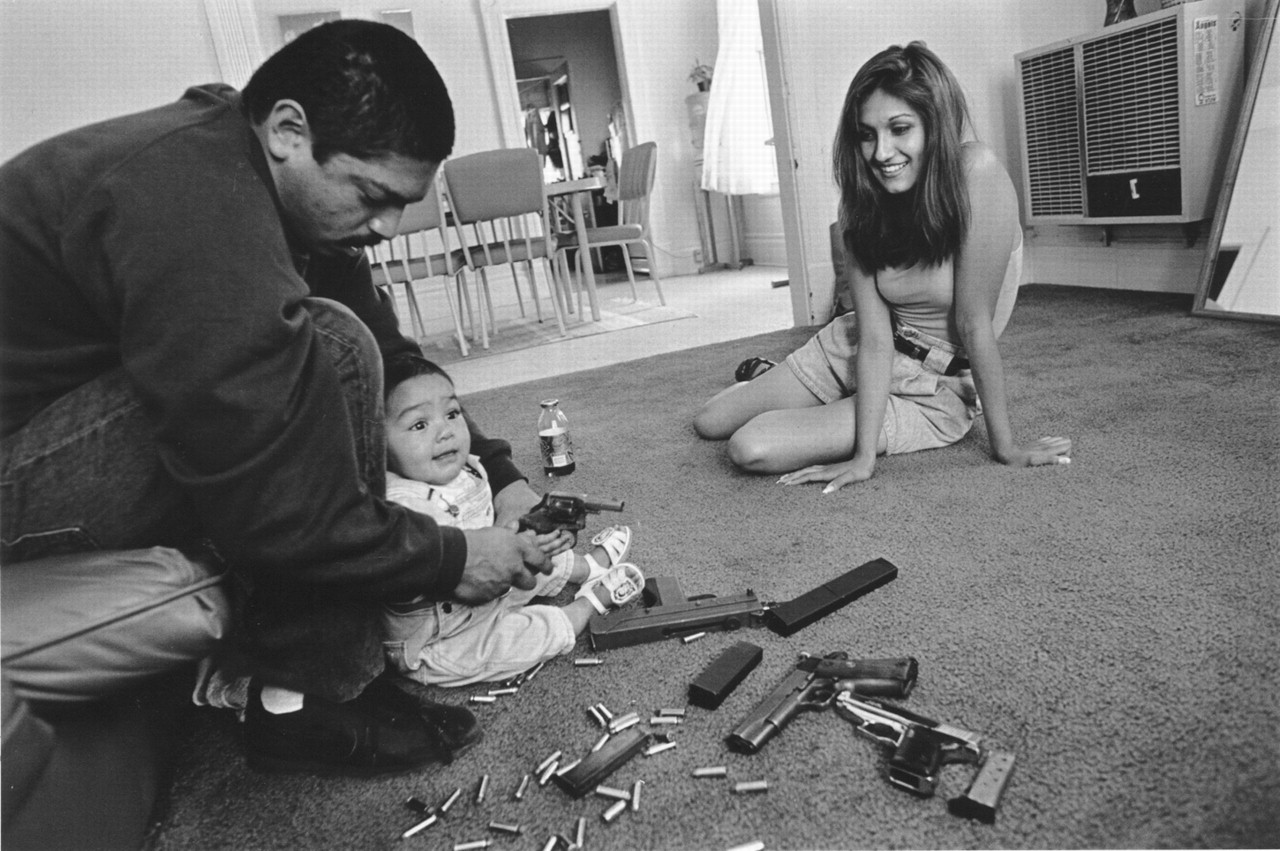

Photos Reveal Gang Life

Award-winning photojournalist Joseph Rodriguez grew up poor on the rough streets of Brooklyn during the 1960s. Drugs were easy to come by, and he became a heroin addict. After serving two prison sentences, Rodriguez decided to turn his life around and studied photography.

“Photojournalism gave me the perfect vehicle to show how people lived everyday amidst poverty, violence, and drugs. Photography also enabled me to detoxify from methadone and carried me through difficult times as a young man.” said Rodriguez in an interview with Psychiatric News.

He has focused much of his career on inner cities and subcultures including the streets of New York’s Spanish Harlem and East Los Angeles, Calif.

Rodriguez said that during the three-year photo project in East Los Angeles, he interacted daily with gang members, often at great personal risk. “Since I was alone on this project, writing in my journal helped me process terrifying and troubling scenes I witnessed frequently. I was very troubled, for example, by the photo I took of Chivo teaching his baby daughter how to hold guns,” said Rodriguez (see photo).

He also has photographed juveniles in trouble with the law, which mirrors his own experience growing up in Brooklyn. His photographs will be published in the book Juvenile this year.

Photos and books by Rodriguez are posted online at www.josephrodriguez.com/biofs.html. ▪