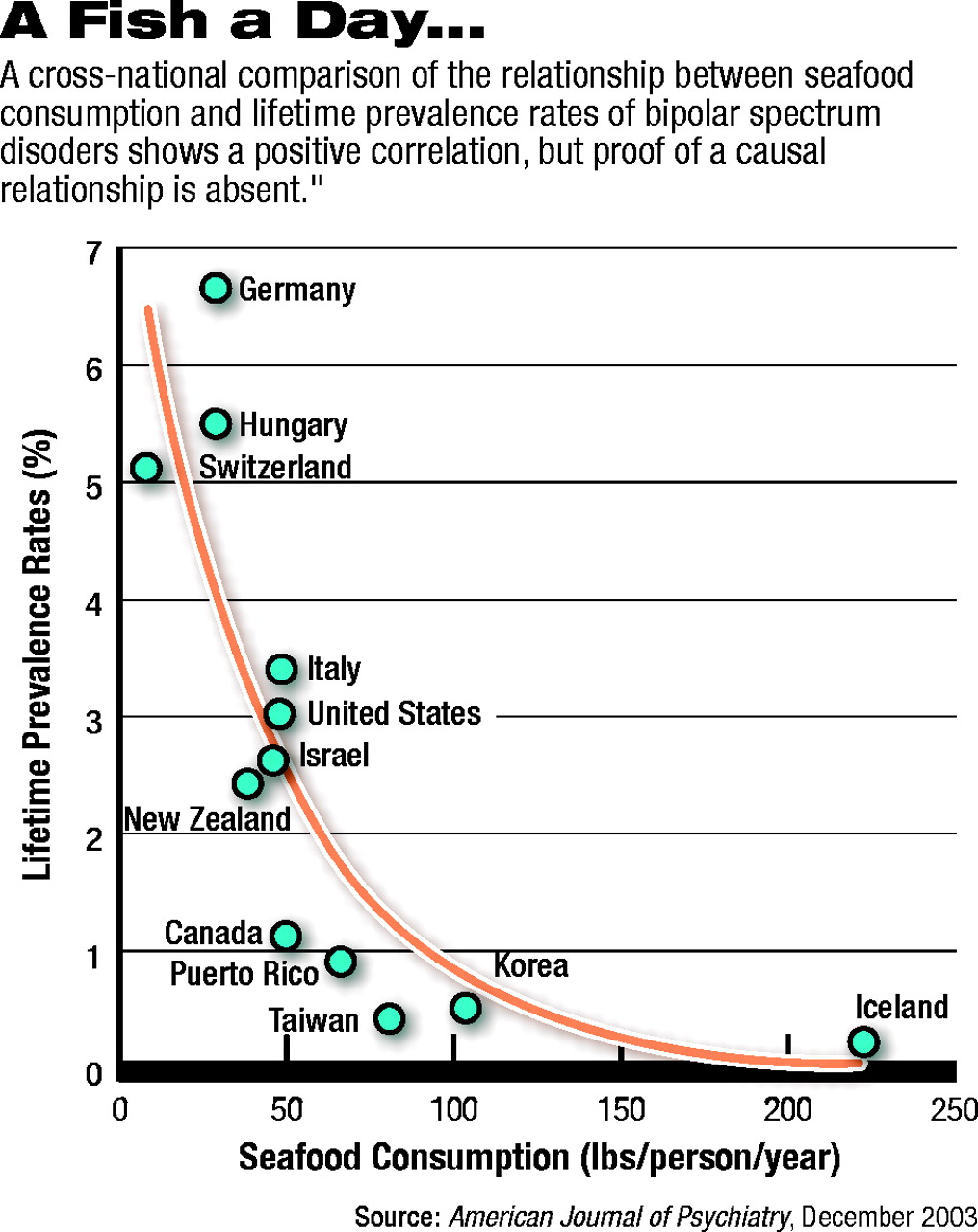

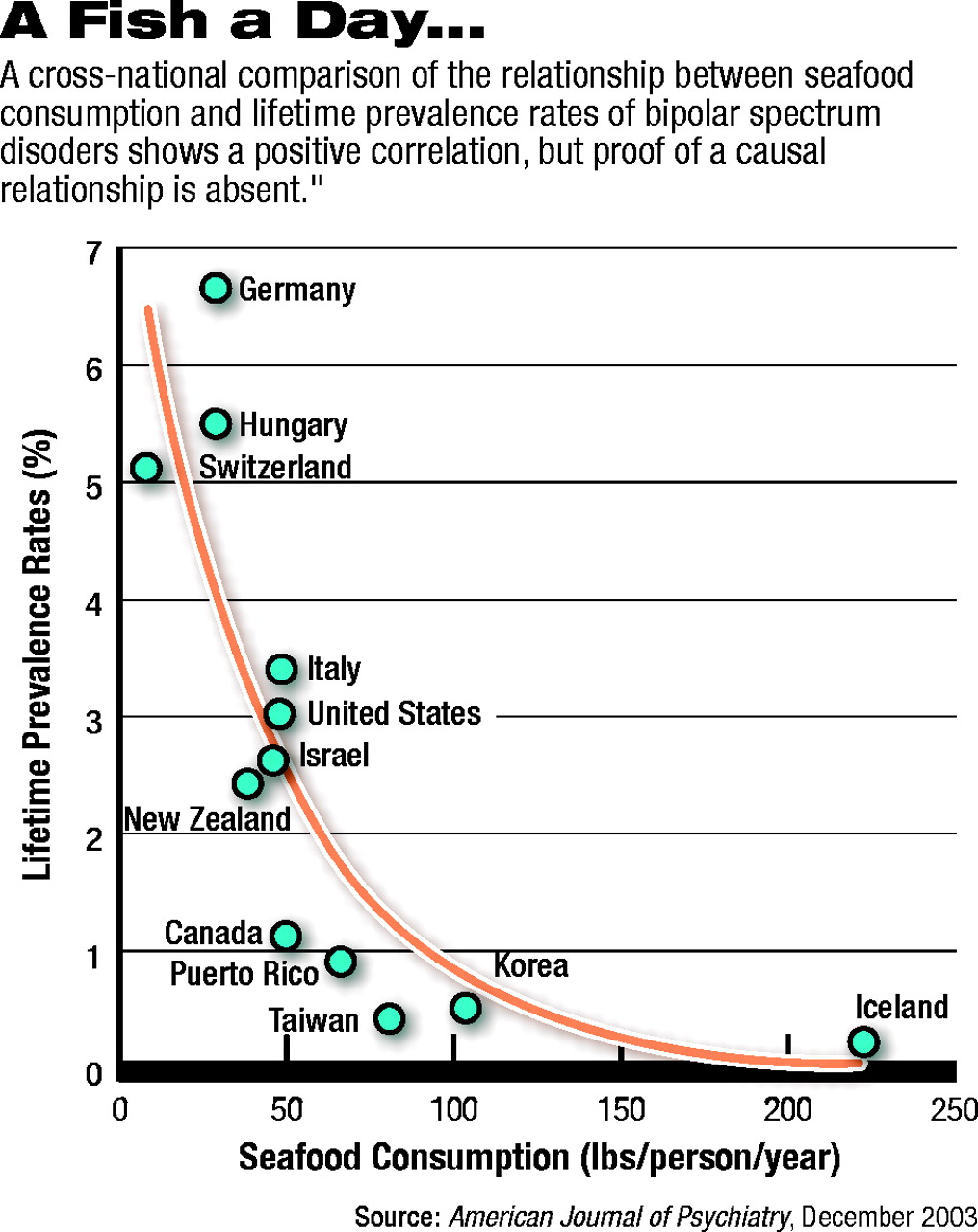

Countries with high rates of seafood consumption appear to have low rates of bipolar disorder.

The finding comes from two psychiatric scientists—Simona Noaghiul, M.D., of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Joseph Hibbeln, M.D., of the National Institutes of Health. It appears in the December 2003 American Journal of Psychiatry.

Noaghiul and Hibbeln first scrutinized the findings of epidemiological studies to determine lifetime prevalence rates of bipolar disorder I, bipolar disorder II, bipolar spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia in a dozen countries. They then examined a document compiled by the National Marine Fisheries Service and the World Health Organization to determine the rates of seafood consumption in these countries during the decade when the epidemiological studies were conducted.

And then they searched for relationships between the amount of seafood consumed in the countries and the lifetime prevalence rates of bipolar disorder I, bipolar disorder II, bipolar spectrum disorder, or schizophrenia.

They found no such relationship as far as schizophrenia was concerned; however, links did appear for bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, and bipolar spectrum disorder. Higher rates of seafood consumption were linked with lower lifetime prevalence rates for all three illnesses.

For example, the lifetime prevalence rate of bipolar spectrum disorder was dramatically higher in Germany than in Iceland. (It was 6.5 percent in Germany, versus 0.2 percent in Iceland) (see chart).

All these results of course, do not actually prove that eating a lot of fish can help prevent the bipolar disorders, Noaghiul and Hibblen admitted in their study report, especially as some well-known risk factors for the disorders—socioeconomic status, rural/urban ratios, marital status, alcoholism, and smoking—were not controlled for in their study.

Nonetheless, they suspect that eating a lot of fish, or at least the omega-three fatty acids that fish contain, may be able to play some preventive role against these disorders—or at least against the depressive aspect of them.

In fact, there is some evidence that eating a lot of fish, or at least the omega-three fatty acids, may be able to combat the depression of bipolar disorder. For example, in 1999, Andrea Stoll, M.D., of McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., and his coworkers reported that bipolar patients taking mood stabilizers plus a dietary supplement of omega-three fatty acids experienced less depression than did bipolar patients getting mood stabilizers alone.

The case is building, too, that fish consumption may play a preventive and therapeutic role as far as unipolar depression is concerned. For example, as Hibblen reported in the April 18, 1998, issue of the Lancet, greater seafood consumption was related to lower lifetime prevalence rates of major depression in nine countries. Lesser amounts of the omega-three fatty acids have been found in the tissues of persons with major depression than in those without. And when infant piglets were given omega-three fatty acid supplements, it doubled the concentration of the nerve transmitter serotonin in their brains.

Am J Psychiatry 2003 160 2222

For example, the lifetime prevalence rate of bipolar spectrum disorder was dramatically higher in Germany than in Iceland. (It was 6.5 percent in Germany, versus 0.2 percent in Iceland) (see chart).

For example, the lifetime prevalence rate of bipolar spectrum disorder was dramatically higher in Germany than in Iceland. (It was 6.5 percent in Germany, versus 0.2 percent in Iceland) (see chart).