Managed care plans that publicly report performance data showed significant gains in quality of care last year on several critical measures, but no gains were recorded on key measures in the treatment of mental illness, according to a report by the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA).

The NCQA's annual report, “State of Health Care Quality,” found that performance improvements recorded last year among the 563 managed care plans that reported their results were among the largest ever. These plans cover about 69 million people and represent a subsection of the broader health care system, according to the NCQA.

Average health plan performance in the area of controlling high blood pressure improved from 58 percent to 62 percent, an improvement that will mean about 2,500 fewer fatal heart attacks this year, according to the NCQA. Health plans are also doing a better job controlling the cholesterol of patients with diabetes; rates for that measure improved from about 55 percent to over 60 percent.

But the NCQA report specifically singled out mental health as an area where the performance of managed care plans has been dismal. Rates for two key measures—follow-up care and medical management of depression—remain generally low and indicate that patients get the correct care only about 50 percent of the time, according to NCQA.

The report is based on results from managed care plans that use the NCQA's Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS), a tool to measure performance on important dimensions of care and service. NCQA is a nonprofit accrediting organization for managed care organizations.

Lawrence Lurie, M.D., chair of APA's Committee on Managed Care, said the NCQA report is a worthwhile effort to measure quality across the health care system, but questioned what health plans are doing to remedy deficiencies in treatment of mental illness.

“What NCQA is measuring is important,” Lurie told Psychiatric News. “Follow-up treatment after hospitalization is an especially critical issue. But the question I would raise is whether health plans are doing anything to provide incentives, or make it easier, for clinicians to meet the performance measures.”

At least one psychiatrist and APA leader expressed deep skepticism about the integrity of the findings. Edward Gordon, M.D., chair of APA's Advisory Committee on Medicare and member of the APA Committee on RBRVS, Codes, and Reimbursement, called NCQA an apologist organization for the managed care industry. “If [the plans] cared about patient needs, they would take a position for parity in mental illness,” he said.

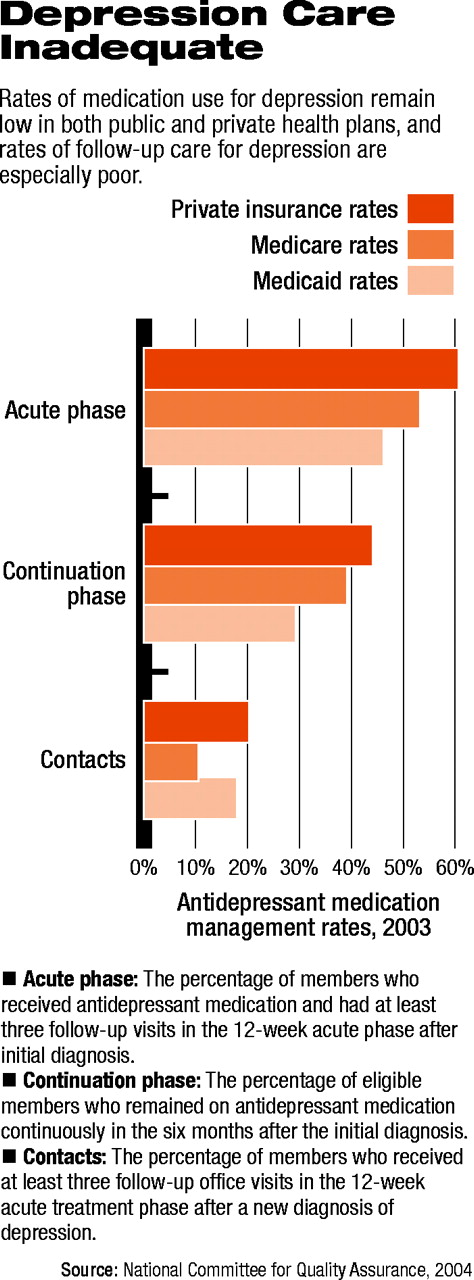

In the area of medical management of depression, the HEDIS measure looks at the percentage of members of a managed care plan with depression who received antidepressant medication during the acute phase (defined as the 12-week period following diagnosis) and the continuation phase (the six-month period following diagnosis). The measure also looks at the percentage of a plan's patients who received at least three visits with a clinician during the 12-week period following diagnosis.

In the commercial market, 60.7 percent of patients were prescribed antidepressant medication during the acute phase, and only 44.1 percent of all patients with depression remained on antidepressant medication continuously during the six-month period following diagnosis. And just 20.3 percent received at least three visits with a clinician during the 12-week period following diagnosis, according to NCQA data.

Rates were even lower for Medicare and Medicaid patient (see chart on page 5).

The HEDIS instrument also measures the percentage of patients in a managed care plan who received follow-up treatment after hospitalization for mental illness.

According to the NCQA report, 74.4 percent of patients in the commercial market had a follow-up visit in the 30-day period following hospitalization last year. Among Medicare patients, 60.3 percent received a follow-up visit, while 56.4 percent of Medicaid patients received a follow-up visit during the 30-day period following hospitalization.

The report is posted online at<www.ncqa.org/communications/SOMC/SOHC2004.pdf>.▪