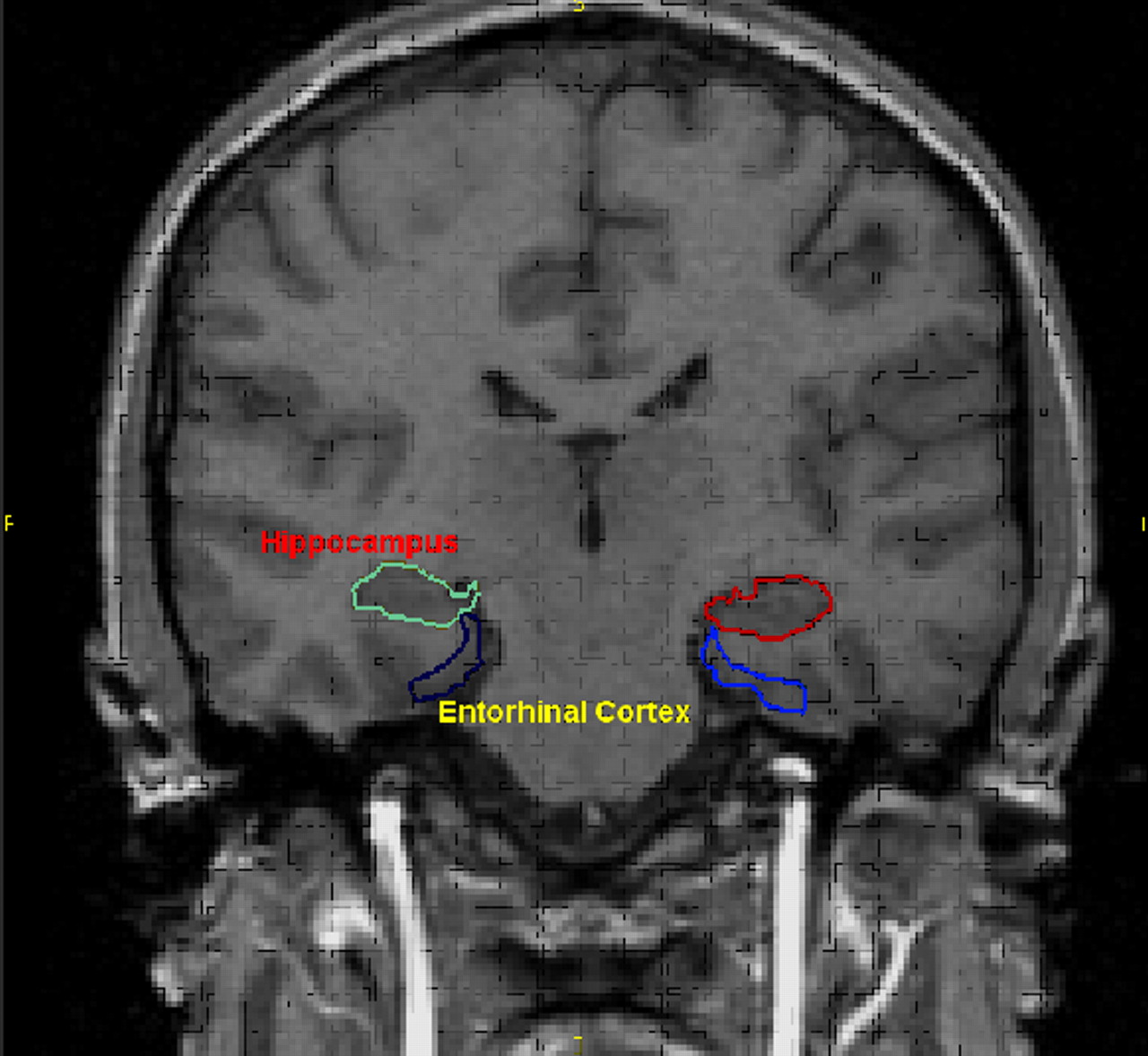

In the murky interior of the brain's left and right temporal lobes can be found the entorhinal cortex. This structure is located not far from the hippocampus and is known to be vital for memory processing.

As the Alzheimer's disease process gets under way in the brain, the entorhinal cortex may be the first brain structure to deteriorate (Psychiatric News, September 1, 2000). Also, small left and right entorhinal cortices have been associated with the delusions of schizophrenia (Psychiatric News, October 1). And now, the entorhinal cortex has been linked with dèjá vu phenomena—that is, the feeling of having already experienced the same place or event before.

The finding comes from Fabrice Bartolomei, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor at the Service de Neurophysiologie Clinique in Marseille, France. Results appeared in the September Neurology.

Dèjá vu experiences are a common feature of temporal lobe seizures and have often been reported after stimulating healthy subjects' medial temporal lobes. Such evidence suggests that the middle area of the temporal lobes gives rise to such experiences. But where in the middle region of the temporal lobes might dèjá vu phenomena arise? Some research has suggested that it might be in the hippocampus and amygdala since electrical stimulation of these structures has, on occasion, provoked dèjá vu experiences in subjects. However, the possibility that dèjá vu experiences might arise from two other structures located near each other in the middle area of the temporal lobes—the entorhinal cortex and the perirhinal cortex—has not been explored. So Bartolomei and his colleagues decided to do so.

From 2000 to 2002, some 100 patients with drug-resistant epilepsy had a comprehensive evaluation at the clinic where Bartolomei and colleagues worked. This included the placement of electrodes in various areas of their temporal lobes to determine where their seizures were triggered and also to map areas in their temporal lobes involved in memory or language. The brain areas stimulated included not just the hippocampus and amygdala, but the entorhinal cortex and the perirhinal cortex.

Bartolomei and his team then focused on 24 of these patients or, more specifically, on the 280 electrode stimulations that these subjects had received to the hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, and perirhinal cortex.

Dèjá vu states, they found, were mostly associated with the entorhinal cortex. They occurred with 14 stimulations of the entorhinal cortex. In contrast, only two stimulations of the perirhinal cortex, two stimulations of the amygdala, and one stimulation of the hippocampus led to dèjá vu.

Interest in Reminiscences

The investigators were also interested in locating the brain source of reminiscences. One subject, for instance, upon stimulation of the amygdala, thought that she smelled the scent of burnt wood. This olfactory hallucination reminded her of sitting around a campfire on a beach in Brittany when she was 14 years old.

However, it was only this one-time stimulation of the amygdala in one subject that produced such reminiscences, the researchers found. Stimulations of the hippocampus or entorhinal cortex provoked no such reminiscences. Yet, in contrast, five stimulations of the perirhinal cortex led to such reminiscences.

“Our study shows that an illusion of familiarity is often obtained after stimulation of the rinal cortices (entorhinal cortices or perirhinal cortices) and more rarely after hippocampal or amygdala stimulation,” the scientists observed in their study report. How stimulation of the entorhinal cortex or perirhinal cortex actually produces such illusions is still a mystery, though, they stated.

Limitations Noted

“Since this study was conducted on treatment-refractory epileptic patients, the findings may not be generalizable to healthy subjects,” Konasale Prasad, M.D., a research fellow at the University of Pittsburgh and one of the investigators who linked entorhinal cortex abnormalities with schizophrenia delusions, said in an interview. “Besides, we are not sure whether the raters who documented and interpreted the findings were blind. A control subject group or within-group control subjects with sham stimulations could have also been used to make the findings more robust.”

Nonetheless, Prasad continued, “the findings are not only very interesting, but very strong and significant for the field of cognitive neuroscience.... This is the best direct evidence of entorhinal involvement in dèjá vu states.”

“The Bartolomei finding in a way explains our entorhinal cortex findings in schizophrenia,” Matcheri Keshavan, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh and another of the scientists who linked entorhinal cortex abnormalities with schizophrenia delusions, told Psychiatric News.

“Perhaps an increased activation of the entorhinal cortex in some schizophrenia patients makes them attach a false sense of familiarity to otherwise neutral events, leading to delusion formation. Thus, in a classic example of a delusion, the patient sees a silver spoon on the table. Rather than dismissing it as an ordinary spoon of no relevance, his entorhinal cortex may attach a dèjá vu–like feeling. The corrupted retrieval of the autobiographic memory system, perhaps involving the parahippocampal gyrus, weaves a delusion around that feeling—`This must mean that I have royal ancestry.'”

The study was funded by the Institut National de la Santè et la Recherche Scientifique and the University of the Mediterranean.

An abstract of the report, “Cortical Stimulation Study of the Role of Rhinal Cortex in Dèjá Vu and Reminiscence of Memories,” is posted online at<www.neurology.org/cgi/content/abstract/63/5/858>.▪

Neurology 2004 63 858