A new study is challenging the status quo with data suggesting that obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in children and adolescents is more amenable to treatment with psychotherapy than with the standard medications prescribed for many years.

The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) was a randomized, controlled trial looking at the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) alone compared with the SSRI sertraline (Zoloft) alone, combined CBT and sertraline, and placebo over the course of 12 weeks. The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

“The basic take-home message from this study is that initial treatment for children and adolescents with OCD needs to include cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy—either alone or in combination with medicine,” said John March, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of psychiatry at Duke University Medical Center and principal investigator of the trial. The POTS results were published in the October 27 Journal of the American Medical Association.

“While medication alone is effective for OCD,” March told Psychiatric News, “it is not as effective as the CBT-containing treatments, and it is troubling and probably no longer acceptable just to rely on medications as monotherapy for pediatric OCD.”

Study Builds on Past Work

POTS is the third combined-modality treatment study sponsored by NIMH in pediatric populations, March noted. The first was the Multimodal Treatment of ADHD (MTA) study, led by Columbia University's Peter Jensen, M.D.; the second was March's Treatment of Adolescent Depression Study (TADS) (Psychiatric News, September 3). Interestingly, he added, the MTA noted no advantage to combined treatment with medication and psychotherapy, while the TADS found that combined treatment was more effective than either treatment alone.

“With POTS, the combination was superior, but not all that much so, to CBT alone,” March said, “and both the CBT-containing treatments were better than medication alone, which was better than placebo. So unlike depression in kids and teens, with OCD it seems to be the psychotherapy that is the big winner.”

March emphasized that the disparate results with medication compared with therapy or the combination for treating pediatric disorders “tells us something about these disorders and what their etiology is.”

He continued, “We really have to think about these disorders as individual conditions that require treatments that are tightly coupled to their targets—whether you conceptualize those targets as behavioral/symptomatic targets or intermediate phenotypes, as in the allocation of attentional resources, or whether you conceptualize them as neural networks with their own particular neuroanatomy. You have to conceptualize these disorders as highly individualized, and one can no longer simply say that one size [of treatment] fits for all.”

Methodology Detailed

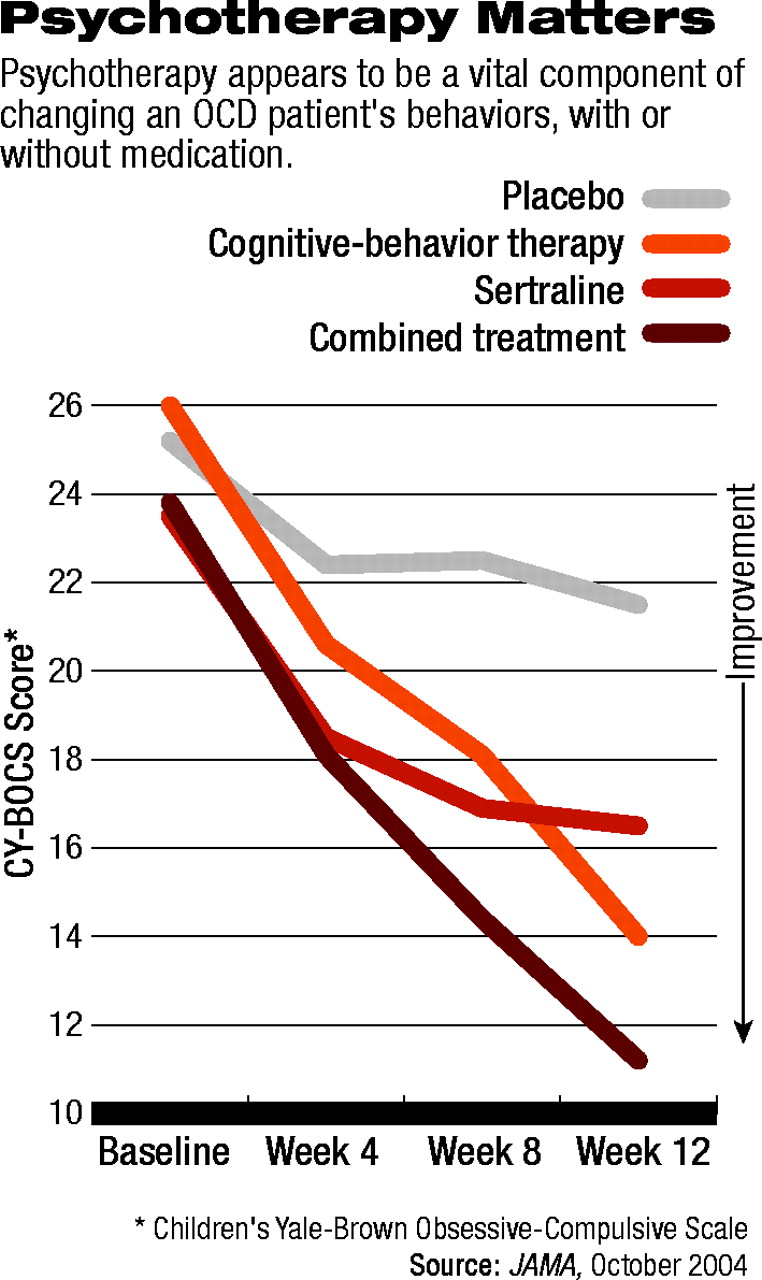

POTS enrolled 112 patients aged 7 through 17 at three academic medical centers in the United States, all with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of OCD and a score of 16 or higher on the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS). Patients were randomly assigned to one of the three treatment modalities or placebo for 12 weeks. The primary outcome measure was the change in CY-BOCS scores over the 12 weeks of treatment, as rated by an independent evaluator who was kept blind to treatment status. A secondary outcome measure was the rate of clinical remission of OCD, defined as a CY-BOCS score of 10 or less.

All three active treatments showed statistically significantly greater improvement over the study's 12 weeks, compared with placebo. Combined treatment also proved superior to CBT alone and to sertraline alone; however, CBT and sertraline did not differ statistically significantly from one another (see graph).

Rates of clinical remission were 53.6 percent for combined treatment, 39.3 percent for CBT alone, 21.4 percent for sertraline alone, and 3.6 percent for placebo. Statistically, remission rates were not different between the combined treatment and CBT alone, and CBT alone did not differ significantly from sertraline alone, but was statistically superior to placebo. Sertraline alone was not statistically superior to placebo on remission rates.

With regard to safety, two patients taking sertraline experienced“ activation” that presented as “increased motor activity” or “impulsivity.” The activation subsided with dosage adjustments. Five patients on sertraline and one on placebo exhibited mild activation symptoms that included mild increases in motor activity but no corresponding increase in impulsivity.

“We had 56 kids on sertraline and 28 allocated to placebo,” March noted. According to the FDA's estimate of suicidal thoughts and behaviors associated with SSRI antidepressants, the researchers would have expected to have two subjects with suicidality, but “we found none. This study was really too small to say anything except that we saw really no hint at all of any suicidality in any of these kids. Also, we saw no mania, hypomania, disinhibition, or increased anxiety—all things that people point to in support of the suicidal association.”

March and his team are continuing their work with the same group of children. “The kids who were responders went on into a discontinuation trial, where we stopped their treatment. The nonresponders were referred for treatment that was appropriate for their particular clinical situation. But what we really want to see, using survival analysis,” he concluded,“ is how many patients relapse over the subsequent four months.”

Those data have not been analyzed yet, March said. He hypothesized that youngsters on CBT would relapse less than the those on sertraline, but it will be interesting to see whether that hypothesis pans out, he said.

JAMA 2004 292 1969