What is it like being not just a psychiatrist, but also the parent of a star athlete who loses star status?

What happens to professional boxers when their careers are on the decline?

These two questions about losing the spotlight in the sports world will be addressed at a symposium at APA’s 2004 annual meeting in New York City next month. The symposium, titled “Contemporary Issues in Sport Psychiatry,” will take place on Tuesday, May 4, from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. in the Javits Center, room 1E14, Level 1.

The symposium will be chaired by Ronald Kamm, M.D., president of the International Society for Sport Psychiatry, headquartered in New York City.

When he was in high school, Alec Baker was a goalie for an elite junior hockey team —a “star.” Then he experienced an injury and lost his star standing. What this experience did to his identity and to that of his parents will be discussed at the symposium not just by Alec, but by his parents, Howard Baker, M.D., a psychiatrist, and Maggie Baker, Ph.D., a psychologist. Tom Newark, M.D., a sport psychiatrist who works with adolescents, will also comment on the subject.

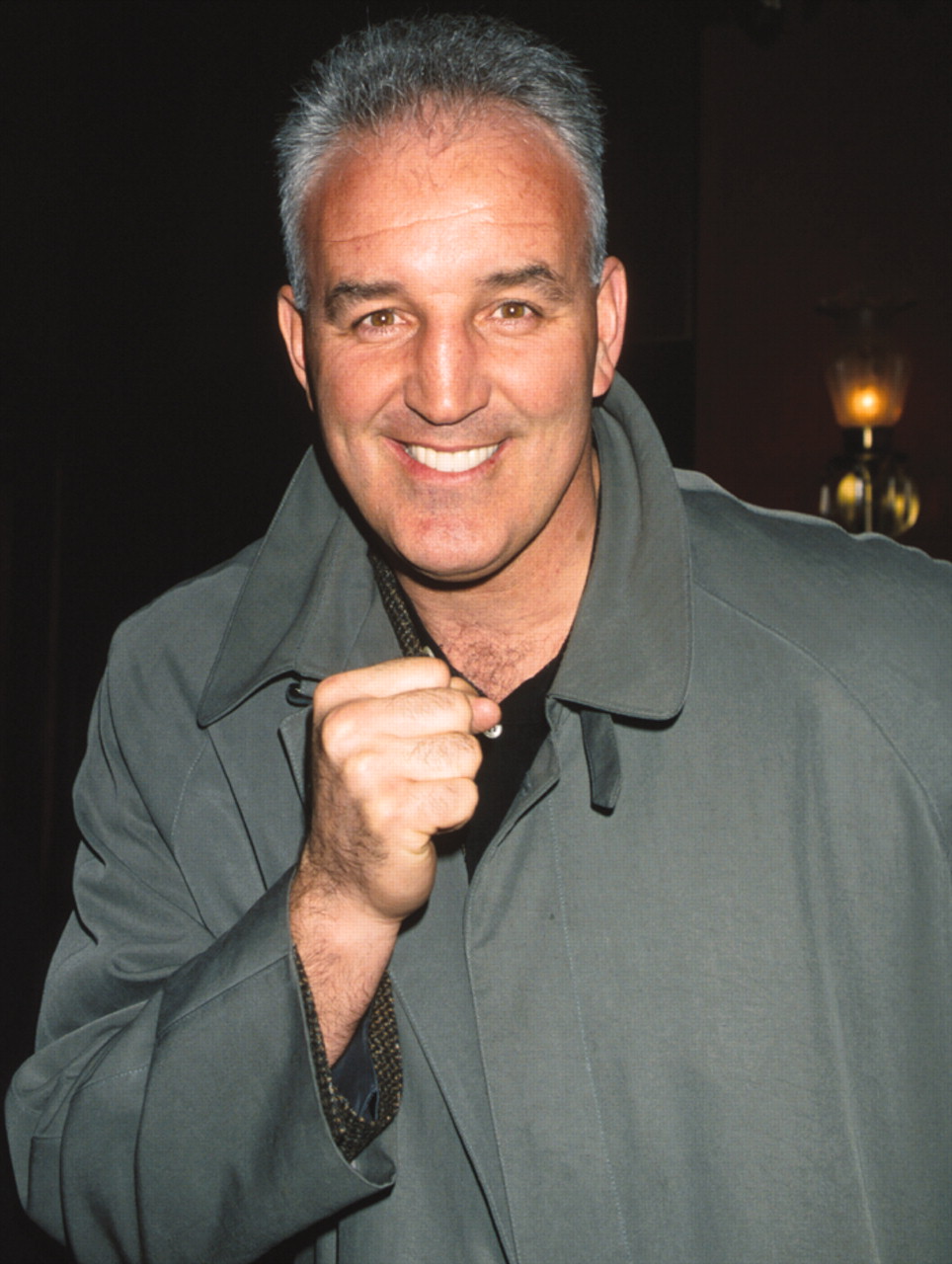

Gerry Cooney, a former professional boxer, will talk about what it was like for him to leave the world of professional boxing and make the transition into the “real” world. He will also talk about an organization he founded in 1998, called FIST (Fighters’ Initiative for Support and Training), which tries to help professional boxers make such transitions. Kamm, who is also involved with FIST, will discuss it as well.

“Career termination is really traumatic for most athletes, but even more so for boxers,” Kamm explained in an interview with Psychiatric News. “They live in a very insular world. Often they are encouraged to drop out of high school by their managers and promoters, and they do nothing but train in the gym and relate to other boxers. Toward the end of their career, they don’t have any other skills, so they stay in boxing too long, and they become opponents or sparring partners, and that is really when the brain damage occurs. So what we’re doing with FIST is giving them an alternative. When their skills are starting to erode, we’re helping them with vocational placement, career-termination counseling, and medical evaluations.”

Other persons on the FIST team, notably its president, Joe Sano, will add their observations.

Stacy Robinson, formerly a wide receiver for the New York Giants and currently director of player development for the National Football League (NFL), will be talking about approaches the NFL uses to try to keep athletes out of trouble. Eric Norse, M.D., a sport psychiatrist who works with teams in the Baltimore area on issues such as violence and drug abuse, will put Robinson’s comments into a sport psychiatry perspective.

There are various reasons why psychiatrists who are not directly involved in sports should attend this symposium, Kamm continued—for example, professional athletes such as Kobe Bryant are getting into legal trouble, the issue of career termination occurs in all sports, and many psychiatric patients engage in sports.

Kamm, in fact, would like to see more psychiatrists become engaged in sports medicine (Psychiatric News, April 4, 2003). “Psychiatrists bring something to the table that sport psychologists don’t have,” he explained. “Being more adept with the biopsychosocial model, we can diagnose underlying disorders and treat them with psychotherapy and medication, as well as using the cognitive-behavioral techniques of the sports psychologists. We are the specialists who most naturally interface with other medical personnel in the care of athletes—pediatricians, orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, and sports medicine specialists.”

More information about Kamm, sport psychiatry, and the International Society for Sport Psychiatry is posted online at www.mindbodyandsports.com. ▪