Psychiatric ill health often goes hand in hand with nonpsychiatric disorders in adults, studies have suggested. The same overlap appears to occur among youth as well, a large Canadian study has found.

The study was headed by Donald Spady, M.D., an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Alberta, and results were published in the March Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine.

According to the Government of Alberta, some 400,000 children aged 6 to 17 visited a family physician, pediatrician, or psychiatrist in Alberta during the province's 1995-96 fiscal year. The physicians used the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) to diagnose the children for psychiatric disorders and nonpsychiatric medical illnesses. Using the diagnostic results for these youngsters, Spady and his coworkers determined how many youngsters had a psychiatric disorder, and how many of those children also had a nonpsychiatric illness. Eight percent of the youth had at least one psychiatric disorder, the researchers found, and of these, 92 percent also had at least one nonpsychiatric illness.

Co-Occurrence Varied

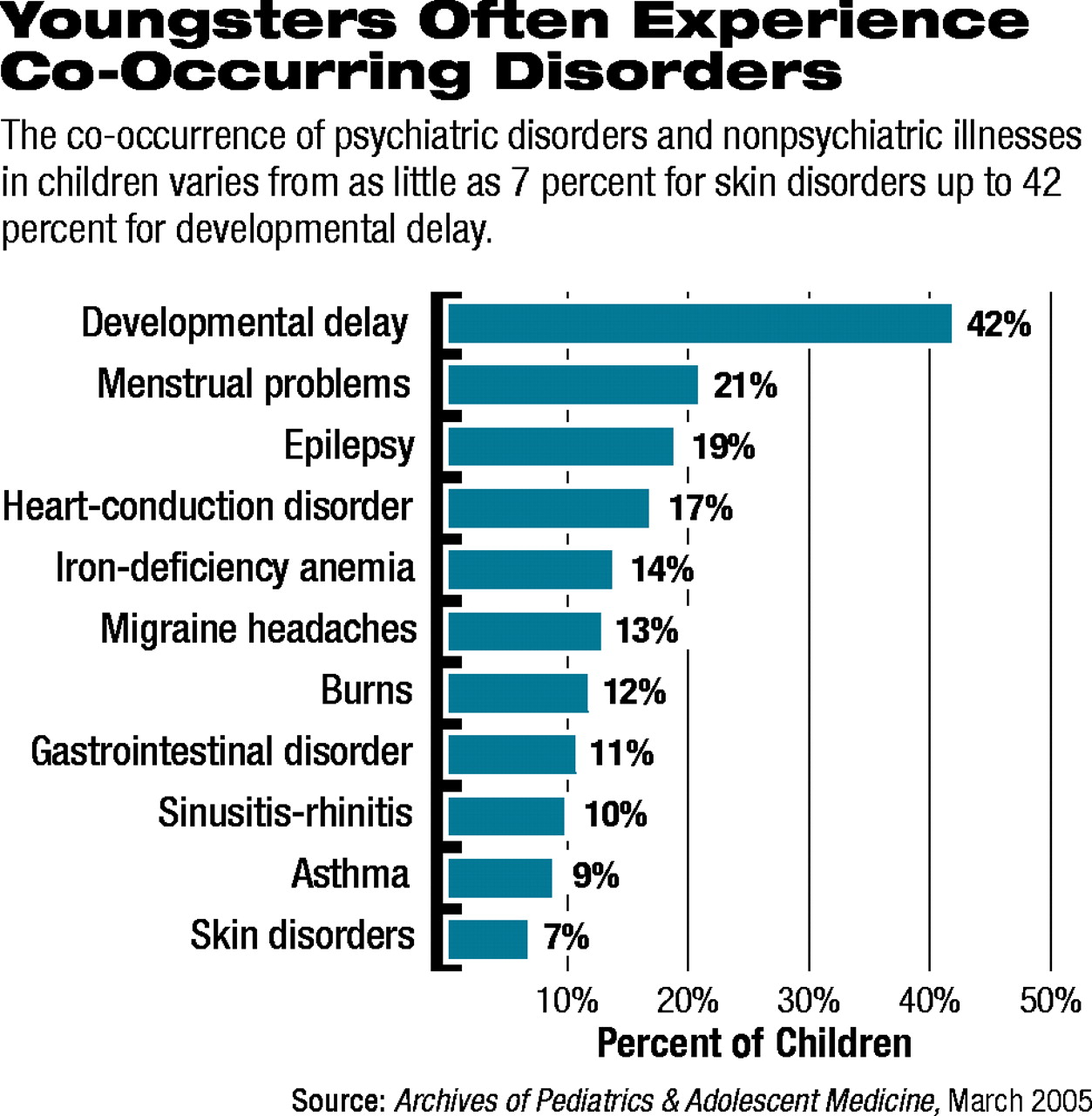

Moreover, the investigators discovered, the co-occurrence of psychiatric illnesses with nonpsychiatric ones varied widely depending on the type of the latter, from as little as 7 percent to as much as 42 percent. Specifically, only 7 percent of the children with skin disorders had a psychiatric disorder, whereas 42 percent of the children with developmental delay did. The percentages of psychiatric illness for children with other kinds of medical illnesses fell between these extremes (see chart).

Because developmental delay is more associated with medical origins and services than psychological, the authors treated it as an independent analysis though it properly falls into the domain of psychiatric disorder.

Finally, Spady and his coworkers grouped the psychiatric disorders in their subjects into three categories—emotional disorders (for example, depression, or an acute stress reaction), behavioral disorders (for example, hyperactivity, drug abuse), and psychosis. They then attempted to see what the odds were of having a specific nonpsychiatric condition in conjunction with one of the three categories of psychiatric disorders. They found that the odds ratios varied quite a bit—from, for example, 1:1 for sinusitis associated with emotional disorders in girls, to 2:1 for a heart-conduction disorder associated with behavioral disorders in boys, to 5:1 for iron-deficiency anemia linked with psychosis in boys.

“It is surprising that such a wide variety of [nonpsychiatric] disorders was associated with psychiatric disorders,” Spady and his team said in their report, “and although the odds ratios are generally small. .it appears that a wide variety of medical illnesses may have psychiatric overtones.”

Be Aware of Comorbidity

The take-home message, Spady told Psychiatric News, is that“ a significant proportion of children with psychiatric disorders often have underlying or associated [nonpsychiatric] disorders, and psychiatrists should be aware of this. In like manner, general physicians should be aware that children can also have psychiatric disorders.”

One of the strengths of this study, Spady said, is that it was conducted not just on children with psychiatric or nonpsychiatric disorders, but on a large population of children. Thus, the links they found between psychiatric and other illnesses “may be less biased than those seen in populations selected for specific mental or physical problems.”

One of the weaknesses of the study, Spady added, is that the data are cross-sectional. Thus, one cannot determine from them whether co-occurring psychiatric disorders and nonpsychiatric disorders have a cause-and-effect relationship or whether they share pathophysiological origins.

The investigators provided the funding for the study.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005 159 231