Why do doctors prescribe the antidepressants they prescribe? Or more specifically, asked Mark Zimmerman, M.D., and colleagues, “If bupropion is as effective as other antidepressants, and it does not cause the side effects that are the most frequent causes of long-term noncompliance, why isn't it the most frequently prescribed antidepressant medication?”

Missing evidence, marketing pressures, and hard-to-break prescribing habits mark the gaps in translating the findings from drug efficacy studies to real-world clinical practice, they wrote in the May Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

The team focused on bupropion because a comparison of side-effect rates of nine new-generation medicines suggested that bupropion had the most favorable side-effect profile, said Zimmerman, an associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University School of Medicine, Rhode Island Hospital, in Providence. The drug is considered less likely to cause weight gain or sexual dysfunction—side effects that loom large in the minds of patients and may reduce their adherence.

The researchers surveyed 10 psychiatrists affiliated with the outpatient practice in the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry, asking them to fill out a 43-item questionnaire for each patient prescribed a first or new antidepressant. They got back 1,137 completed questionnaires between August 2001 and February 2002 recording factors influencing their choice of a newly prescribed antidepressant. Over half the prescriptions (669, or 58.8 percent) initiated antidepressant treatment, 26.6 percent reflected switches from one drug to another, and 9 percent covered augmentation of prior treatment.

No funding from pharmaceutical companies was sought or received to support the study or the resulting article, said the authors.

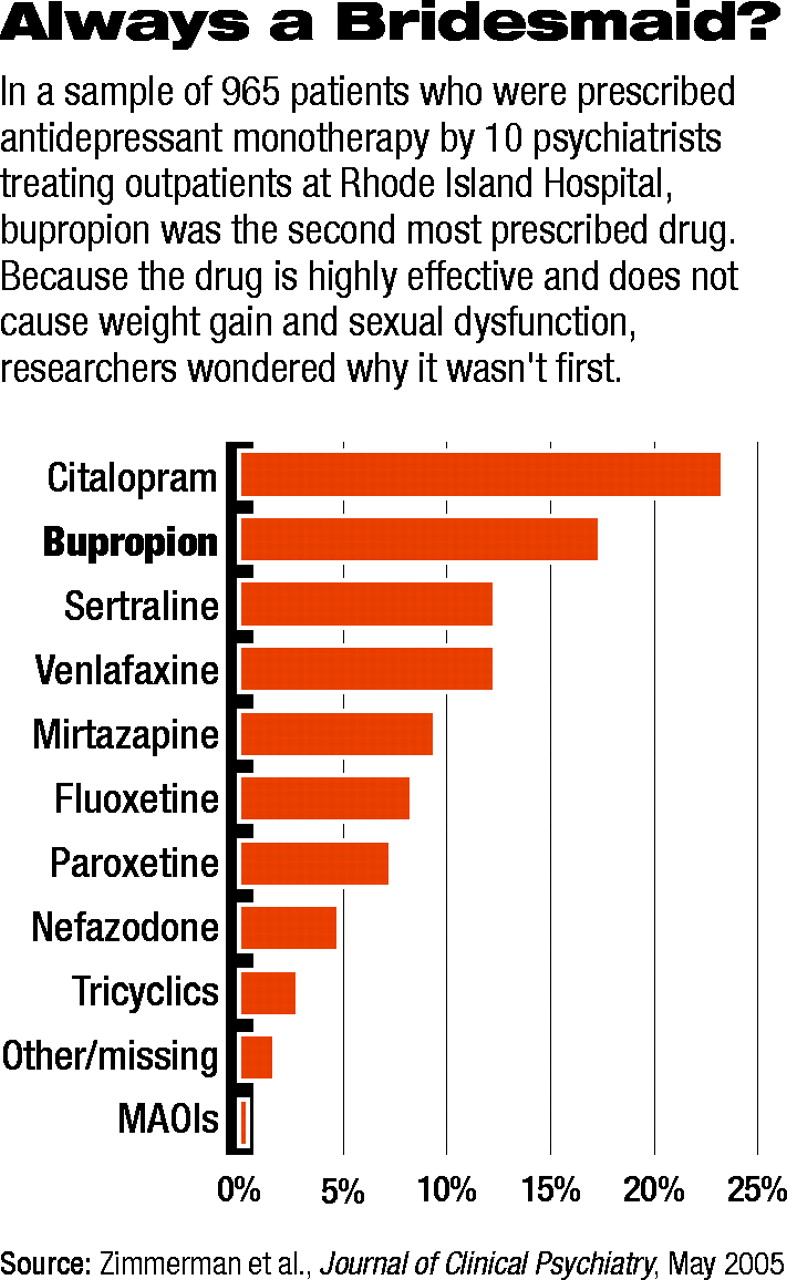

The most commonly prescribed antidepressant was citalopram (23.3 percent), with bupropion in second place (17.4 percent). Sertraline and venlaflaxine each accounted for 12.3 percent of prescriptions (see table on page 20). Bupropion's bridesmaid status was confirmed when it was prescribed significantly more often than other drugs to augment existing regimens. Since the reasons for choosing a medication for augmentation might be different from those for initial monotherapy, the researchers excluded augmentation prescriptions. That left 965 patients for analysis.

“Overall, the most common influences on antidepressant choice were the avoidance of side effects, the presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, and the presence of specific clinical symptoms,” wrote Zimmerman and colleagues. Prior positive or failed treatment response was the next factor most often cited.

Avoiding specific side effects and targeting specific symptoms were the most frequent reasons given for using bupropion, while the presence of a comorbid condition was cited less often. Comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, eating or sleeping too much, and fatigue were given more often as reasons in favor of prescribing bupropion. Doctors less often cited generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, poor sleep or appetite, irritability, or high anxiety levels as justifying bupropion.

“The DSM-IV's approach toward identifying phenomenologically homogenous subtypes of major depressive disorder, based on the presence of atypical or melancholic features, rarely influenced the choice of medication,” they said.

“They've detected a real phenomenon,” said psychiatrist Greg Simon, M.D., M.P.H., an investigator at Group Health Cooperative in Seattle, in an interview. “But where does that perception come from? Evidence is only a small part of it.”

Doctors develop brand loyalty, some of it justified by their experience with a drug, said Simon. Some doctors always use one drug, while others always use another.

“A lot of money is spent to develop those allegiances, but physicians may also just recall the words of a venerated med school professor when they prescribe,” he said.

The key to when bupropion is prescribed may lie in anxiety, at both the symptom and disorder level, suggested Zimmerman. Bupropion has been shown effective for the treatment of depression alone or in combination with anxiety, but there are few published data on the efficacy of using it for anxiety in the absence of depression. However, nervousness, anxiety, or agitation are no more common among patients using bupropion than SSRIs and other newer drugs.

The FDA has approved many of those new drugs—but not bupropion—for treating anxiety disorders.

“Clinicians may infer greater efficacy because of the literature demonstrating efficacy of these medications in anxiety disorders and the approval of these medications for the treatment of these disorders,” wrote the researchers, even though no studies demonstrate superiority of other new-generation antidepressants for depressed anxious patients. There might also be a difference between clinical-trial findings and the reality of clinical practice, if efficacy trials excluded highly anxious patients. Pharmaceutical companies' marketing practices might also influence drug selection, they said.

Future studies, open to patients with varied comorbidities and closer examination of physicians' prescribing patterns, may offer insight into the best ways to use these drugs.

An abstract of “Why Isn't Bupropion the Most Frequently Prescribed Antidepressant?” is posted online at<www.psychiatrist.com/abstracts/200505/050509.htm>▪