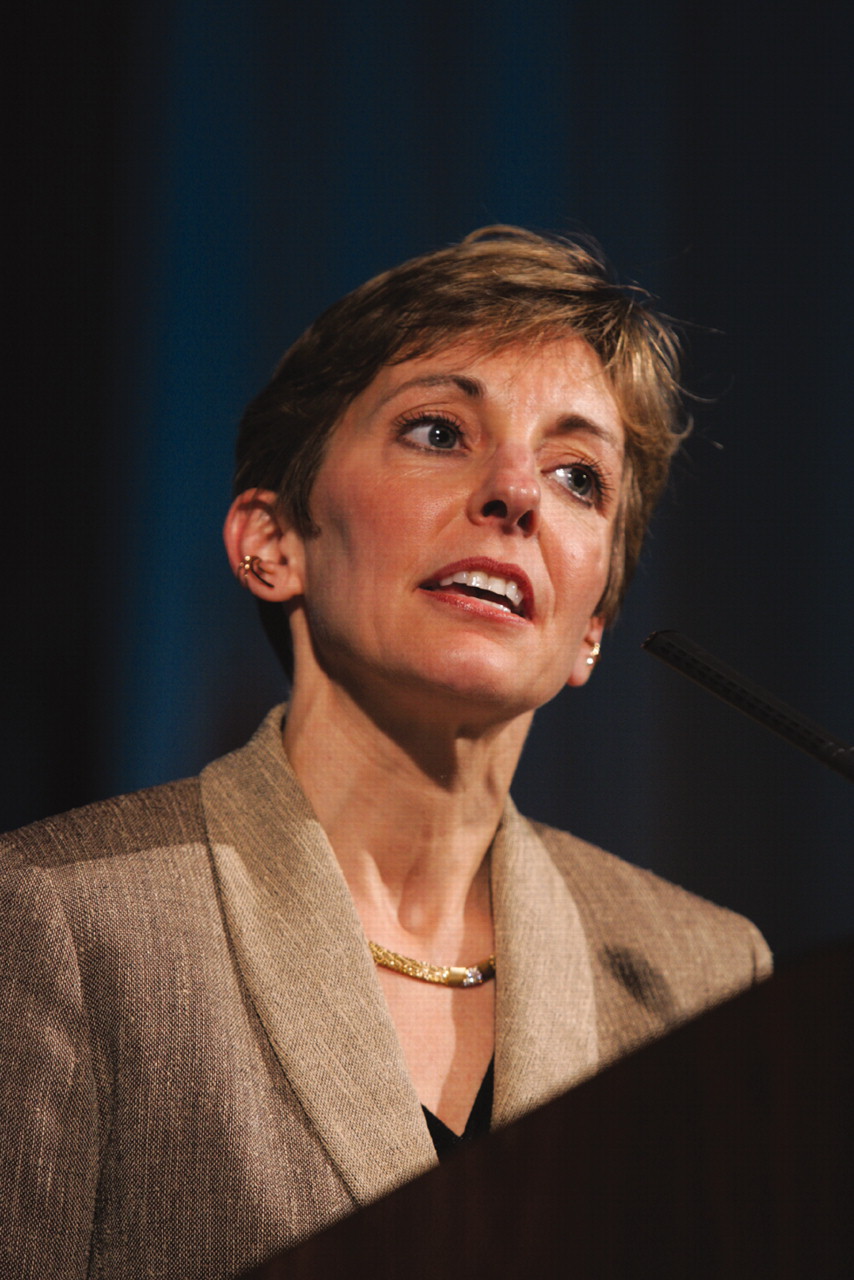

Her name is Trisha Meili, and psychiatrists at APA's 2005 annual meeting in Atlanta got a glimpse of the person behind the moniker by which she became known to millions as a symbol of brutal urban violence—“the Central Park jogger.”

Delivering the William C. Menninger Convocation Lecture at the 49th Convocation of Distinguished Fellows, Meili described a remarkable journey toward recovery following the heinous 1989 attack in New York's Central Park in which she was raped, severely beaten, and left for dead. The attack made headlines around the world.

At a meeting focused on psychosomatic medicine, Meili's story of recovery demonstrates the need for general medicine and psychiatry to intersect. Her journey back to health and wholeness has involved the collaborative work of psychiatrists, social workers, experts in rehabilitation medicine, neurology, ophthalmology, internal medicine, and others.

Fourteen years after the attack, Meili revealed herself and her story in a best-selling memoir, I Am the Center Park Jogger: A Story of Hope and Possibility.

Today, she speaks at universities, brain-injury associations, sexual assault centers, and hospitals about her recovery. She also gives her time to the Sexual Assault and Violence Intervention Program at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City; to Gaylord Hospital in Wallingford, Conn., where she received much of her rehabilitative care; and to the Achilles Track Club, which helped her run in the New York City Marathon in 1995.

In her lecture, Meili distilled her experience into four vital lessons: the importance of “feeding the psyche,” the power of living fully in the moment, aggressively pushing the boundaries of what is considered possible, and self-acceptance.

Meili said the prayers, gifts, and warm words of encouragement that came from family, friends, and strangers from the around the world—even when she was in a coma and unable to speak—fed her psyche.

She recounted with special feeling the care she received from a West Indian nurse in the very early days of her recovery, when she was still in a coma. When doctors would stand over Meili's bed discussing her bleak prospects as if she were not in the room, Meili's nurse would cradle her in her arms and whisper in her ear, “Don't pay them any mind. What do they know? You are a hero.”

“Later, when I did begin to talk,” Meili recounted, “she would ask me, `Who is the captain of the ship?' I would say, `I am,' and she would say, `You're absolutely right!'

“In hindsight,” Meili said, “it was exactly what my psyche needed to hear.”

The power of living fully in the present moment was brought home to Meili by virtue of the fact that as she was painstakingly recovering the use of body and her mind, “nothing came naturally,” she said.

She recalled a rehab exercise she practiced with a nearly meditative intensity, a task designed to help her regain manual dexterity requiring her to remove and replace nails in holes drilled in a wooden board.

“I wanted to regain the full use of my hand, so I was entirely focused on the task directly in front of me,” she said. “I wasn't thinking about what had happened to me. The past I couldn't change, and I didn't seem to be preoccupied about the future. Working in the present moment was the right place to focus my energy.”

The third lesson Meili imparted was about the need to push the boundaries of what one is capable of, and in her recovery she discovered that neuroplasticity was no mere theory.

“I have continued to grow in my recovery by pushing to the edges of what I thought was possible,” she said. “Small improvements motivated me to keep pushing ahead, and the process of growing and healing never stopped. From the improvements over many years I became more confident of what I could do, because I learned to live inside this body and mind.”

Self-acceptance, especially in terms of accepting that the attack had permanently altered some aspects of her cognitive functioning, was the most difficult lesson that recovery from trauma taught her.

“I came from a family that valued intellect, and I was proud of my academic achievements,” Meili said. “I heard many messages growing up, spoken and unspoken, that smart was good....

“Mentally I will never be the same as I was before the attack. To acknowledge this to myself is, to say the least, not a great feeling. But in another way it gives me peace. I accept it. I can live with it. It's a giant step in my healing. It's part of the woman I have become, and, most days, I like that woman.” ▪