The first wave of results from the National Institute of Mental Health's Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) garnered widespread media attention that may have contributed in part to widely divergent conclusions about which antipsychotic medication is most effective.

The media's extensive coverage of the CATIE results was indicative of the study's importance. Launched by NIMH in 1999 with an initial five-year funding of $44 million, CATIE is the largest and longest medication-treatment study of patients with chronic schizophrenia. Researchers followed more than 1,400 patients for up to 18 months.

The results were published in the September 22 New England Journal of Medicine and included data from phase I of CATIE's three planned phases.

The methodology was both complex and comprehensive, as researchers carefully designed the study to mirror real-world treatment conditions of patients with chronic schizophrenia, but subject to stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Patients were randomly assigned to one of five antipsychotic medications: the second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal), and ziprasidone (Geodon) or the first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) perphenazine (Trilafon). Neither the patients nor their clinicians knew which drug patients were taking.

Patients who responded well to their assigned medication continued on that drug for up to 18 months. Patients who discontinued their phase I drug were randomly assigned to a different drug during phase II of the trial. Phase II included the four SGAs from phase I and added clozapine (Clozaril); however, it did not include perphenazine. In phase III, patients who discontinued their phase II medication could choose to continue with open-label treatment with another FGA, SGA, or a combination therapy.

The public announcement of the phase I results last month sparked a media frenzy. Newspaper headlines reflected various—and sometimes contradictory— interpretations of the study's conclusions.

For example, the Star-Ledger of northern New Jersey, home to numerous pharmaceutical companies, ran the headline: “Study: Drug Built in 1950s on Par With New Meds,” while in Indianapolis, home of olanzapine maker Eli Lilly and Co., the Indianapolis Star ran with“ Zyprexa Out-performs Rivals in U.S. Study.”

At the same time, clinicians across the country were beginning to draw their own widely varying conclusions. Clinicians told Psychiatric News such disparate conclusions as “now all the standard neuroleptic users can come out of the closet” and “olanzapine could well become the drug of first choice” contrasted with“ olanzapine is likely to be used second line for patients who haven't responded to other drugs.”

The differing and even contradictory interpretations aren't just academic. Within a week of the study's publication, some experts began to fear that misinterpretation of the study's results and conclusions could have a negative impact on regional and even national health care policy regarding access to antipsychotic medications (

see box.)

Drugs Differ in Efficacy, Tolerability

The principal investigator of CATIE is Jeffrey Lieberman, M.D., chair of psychiatry at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons and director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute. CATIE included 1,432 patients with schizophrenia at 57 clinical sites (Psychiatric News, May 18, 2001).

Lieberman said during a media briefing on the study that CATIE was born out of the need to answer three main questions: Are the newer, second-generation, or “atypical,” antipsychotics (SGAs) more effective than the older, first-generation, or “conventional,” antipsychotics (FGAs)? How do the newer SGAs compare with each other? Are the more expensive SGAs cost-effective?

“The results of the CATIE study provide the most comprehensive set of data on the pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia ever assembled,” Lieberman added. “These data will guide doctors in their selection of treatments and clinical management of patients.”

The phase I findings indicate that “all these medications work,” Lieberman said, “but they also have substantial limitations.”

The primary outcome variable measured was length of time patients took the medication to which they were randomly assigned at the start of the study. The measure of length of time to discontinuation, for any reason, was chosen by the CATIE researchers “because stopping or changing medication is a frequent occurrence and major problem in the treatment of schizophrenia,” the team wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine report. The measure “integrates patients' and clinicians' judgments of efficacy, safety, and tolerability into a global measure of effectiveness that reflects their evaluation of therapeutic benefits in relation to undesirable effects.”

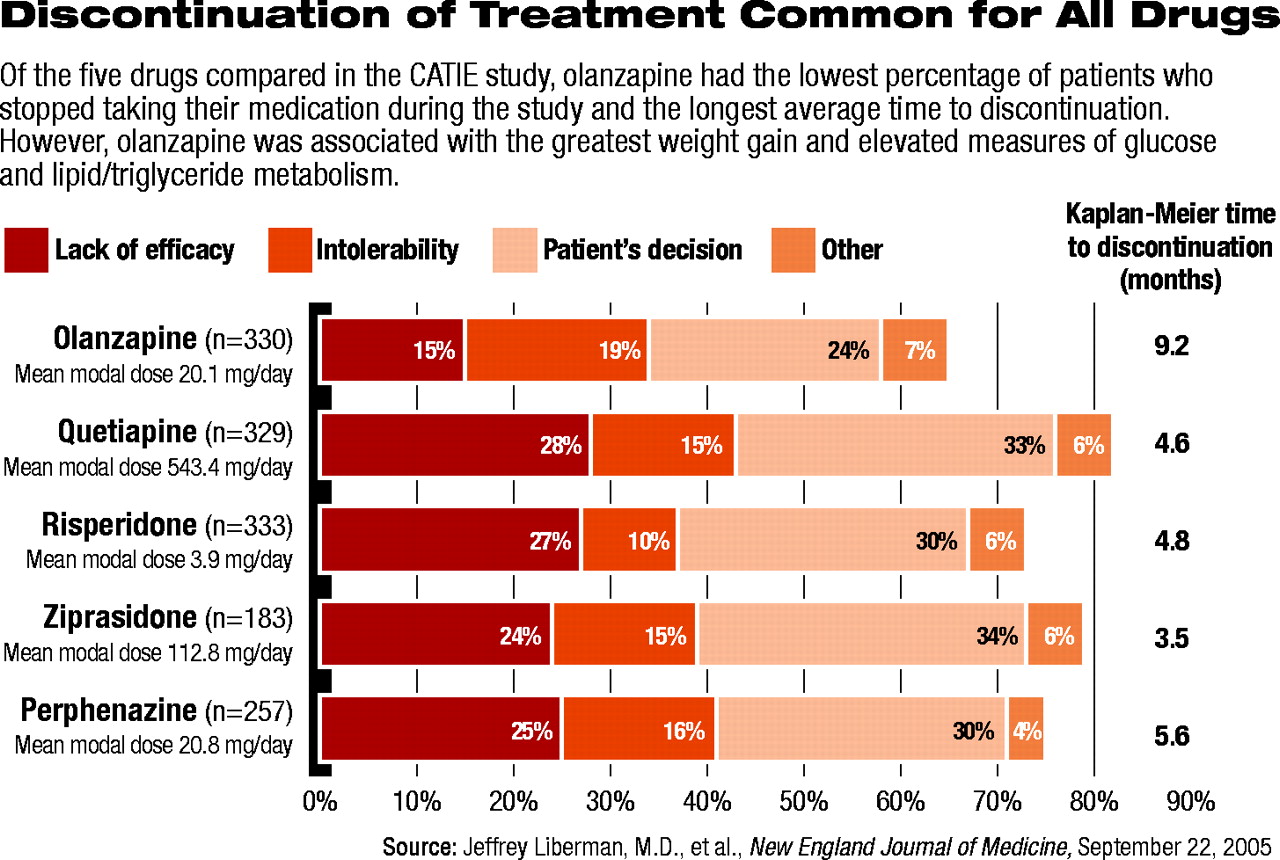

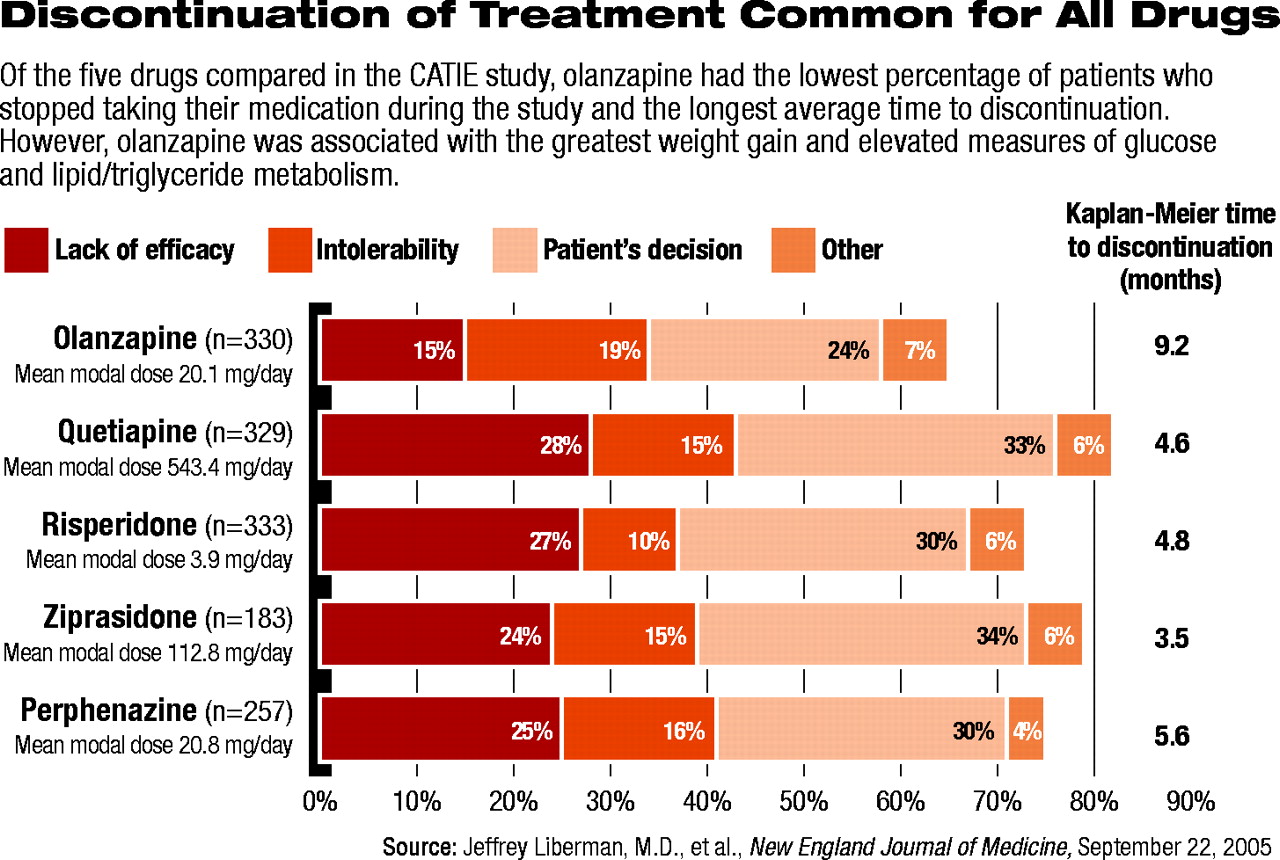

Three-fourths of the patients stopped taking their initially assigned antipsychotic medication before the end of the 18-month study (see chart). Fewer patients discontinued olanzapine (64 percent) than any of the other four medications (between 74 percent and 82 percent). Moreover, patients taking olanzapine stayed on their medication the longest (an average of 9.2 months), while those on the other four medications discontinued their medication significantly earlier (having stayed on them an average of between 3.5 and 5.6 months).

Fewer patients stopped taking olanzapine because of a lack of perceived efficacy compared with perphenazine, quetiapine, and risperidone. (The difference between olanzapine and ziprasidone, however, was not statistically significant.) Overall, there were no significant differences between the drugs in the percentage of patients who stopped medication because of intolerable side effects. Risperidone had the lowest rate of discontinuation due to intolerable side effects (10 percent), while olanzapine had the highest rate (18 percent).

Differences in the medications were also seen in side-effect profiles, with statistically significant differences found in extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), weight-gain and metabolic effects, insomnia, and elevations in prolactin. More patients reported EPS with perphenazine than with any other drug, a statistically significant finding, while more patients reported weight gain of greater than 7 percent of body weight with olanzapine. Olanzapine was also more likely to be associated with elevated measures of both glucose and lipid/triglyceride metabolism, while risperidone was more likely to be associated with elevated prolactin levels.

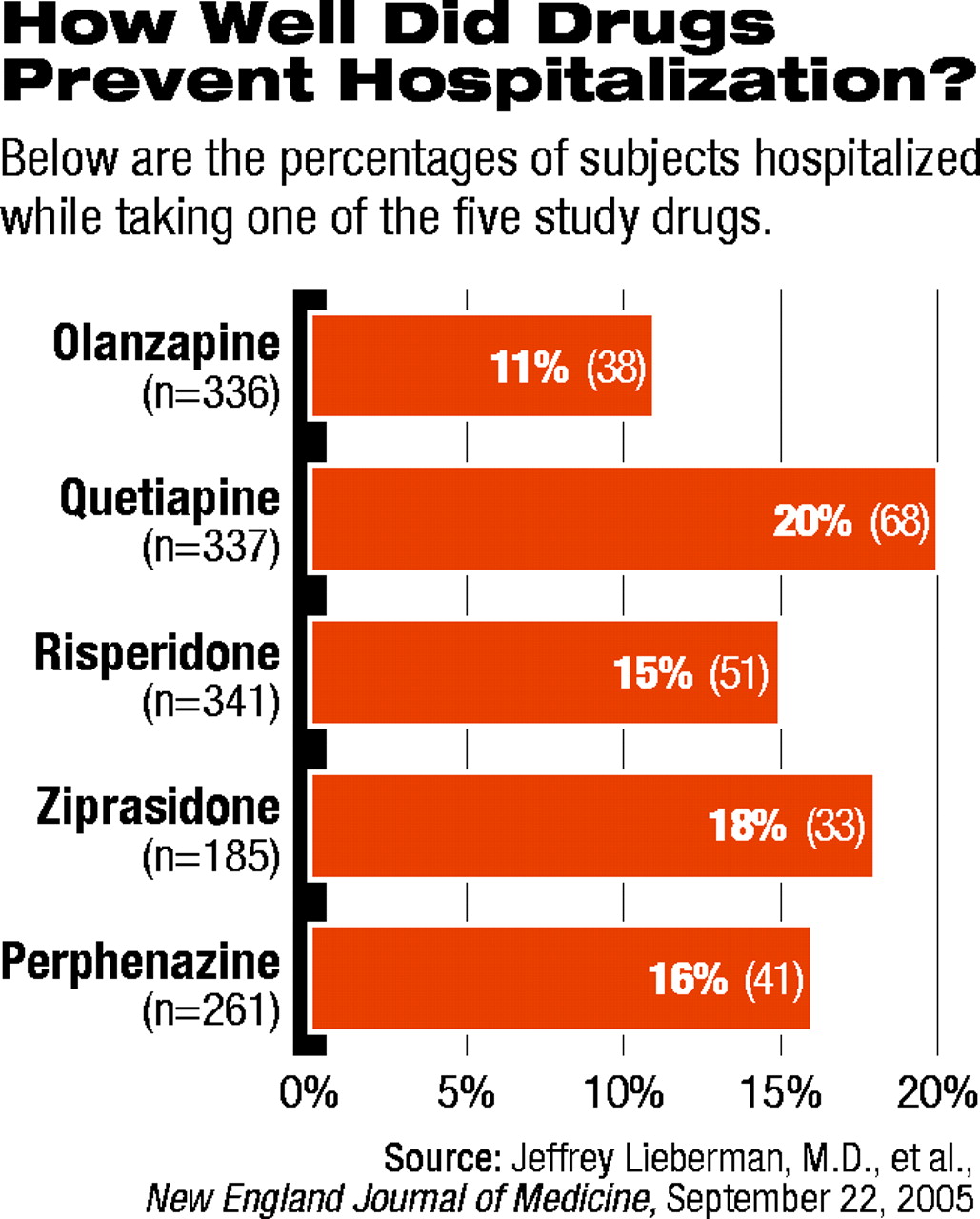

Even so, the average duration of treatment was the longest in those randomly assigned to olanzapine. In addition, significantly fewer patients taking olanzapine required hospitalization during the study for exacerbation of their schizophrenia (see chart on page 1).

Overall, the CATIE researchers reported that “olanzapine was the most effective in terms of the rates of discontinuation, and the efficacy of the conventional antipsychotic agent perphenazine appeared similar to that of quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. Olanzapine was associated with greater weight gain and increases in measures of glucose and lipid metabolism.”

Thus, it turns out that the headlines in both the Star-Ledger and Indianapolis Star were not entirely off the mark, even though they appeared to contradict each other. CATIE had indeed shown that olanzapine appeared to be superior (on certain measures), while perphenazine appeared to be comparable (on certain measures) to three of the newer SGAs.

Qualifications, Questions Abound

Within hours of the release of the CATIE findings, clinicians and researchers not involved with the study raised significant questions about the study's methodology, including issues that could affect interpretation of the findings.

The most significant appears to involve the dose ranges used in the study. The dose ranges were designed to be a best estimate, relying on input from FDA-approved labeling, clinical experience, and the pharmaceutical companies that manufacture the medications.

“Our general feeling,” said Robert Rosenheck, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Yale University and a co-investigator on CATIE, “was that the actual dosing in the end was somewhat higher for olanzapine [compared with doses used in other studies], and the dosing for risperidone was somewhat lower.”

Other researchers were quick to point out that the differences in dosing could have biased the overall effectiveness of the medications. The antipsychotic effect of the medications studied in CATIE is thought to be related to their ability to bind to and block D2 dopamine receptors in the brain, noted John Newcomer, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Washington University at St. Louis.

“In CATIE, olanzapine was dosed at or above its D2 receptor-binding threshold,” Newcomer said. “At higher doses, D2 binding is increased, and presumably, you might see better efficacy.”

However, Newcomer continued, the other four medications were dosed at or below their D2 receptor-binding thresholds, potentially reducing their efficacy trial. “Ideally,” he said, “you would want to see each of the drugs used at doses that produce equivalent D2 blocking.”

Other researchers and clinicians questioned the use of perphenazine as the comparator representing the older FGAs. Many believed that a primary difference between the FGAs and the SGAs was the relative absence of EPS such as akathisia, parkinsonism, and other movement disorders associated with the newer medications. In general, other studies and clinical experience have shown that over half of all adult patients taking FGAs for five or more years developed significant EPS, and some 30 percent to 50 percent developed tardive dyskinesia (TD). Rates are thought to be even higher for elderly patients (see article above).

Among the older antipsychotics, perphenazine is considered to have moderate potency. The more commonly used FGA, haloperidol (Haldol), is considered a high-potency FGA. Higher-potency FGAs have long been thought to have higher efficacy in treating psychotic symptoms, but they are more frequently associated with EPS.

The CATIE researchers chose perphenazine precisely because of its moderate potency, Lieberman explained, and they administered the drug at moderate doses to help avoid any EPS. Indeed, patients who entered the study with tardive dyskinesia (TD) were not assigned to the perphenazine group because the risk was thought to be unacceptable.

“Because people who started the study with TD were selectively randomized,” said John Davis, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Illinois, Chicago, “it makes any comparison of TD rates between these five medications problematic.”

As a result, comparisons of CATIE patients who discontinued their medication because of EPS are “very difficult to interpret,” said Davis, who was not involved in the study.

Yale's Rosenheck said that the study “was not a horse race—it didn't produce a winner,” he said. “Each drug has benefits and risks. Doctors will have to judge what works best for a particular patient.”

In the end, most of the experts interviewed for this article agreed that the history of patients who participated in CATIE has a bearing on the application of the results to patients in clinical practice.

With an average age of around 40 years and an average length of time on antipsychotic medication of over 14 years, the patients followed in CATIE are likely to have taken multiple medications prior to entering the study. These are not patients who have acute or new-onset illness, noted Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., executive director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education and director of research at APA.

Indeed, Regier added, “the 70 to 75 percent of patients on medication at baseline needed to be tapered off prior to treatment before they could be started in one of the study treatment arms.”

Lieberman emphasized that the overall message from the initial CATIE phase I report should be that “each of these medications is effective, and each medication has its limitations.”

He added, “Despite the overall comparability of the treatments in the study, there were variations in the therapeutic and side-effect profiles of each of the drugs. And these can be substantial for patients. It indicates that diverse response characteristics and treatment needs of individual patients require a wide range of medication choices.”

Lieberman noted that several more reports are to be published regarding full results of the CATIE study, including further analyses of phase I data. In addition, phase II and III data will be reported, as well as analyses of differential effects of the medications on the cognitive and negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia. The team is also working on a cost-effectiveness analysis.

The first of those reports should be submitted for publication within six to nine months, Lieberman said.

N Engl J Med 2005 353 1209