Based upon the number of sessions devoted to the topic at the recent annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), the debate over the existence— and definition—of pediatric bipolar disorder is alive and well.

However, the focus of the debate appears to have shifted a bit. After many years of deliberation, the existence of “true mania” (and therefore the potential existence of bipolar disorder itself) in children, appears to be generally agreed upon. The majority of child and adolescent psychiatrists seem to concur that while rare, distinct episodes of mania that would meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder, can and do occur in children, said Kiki Chang, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at Stanford University.

“Bipolar II,” Chang continued, “is harder [to diagnose in children], but still definable.” Chang chaired one of many sessions on pediatric bipolar disorder during the AACAP annual meeting in Toronto in October. “BP-NOS [not otherwise specified], is harder even still,” he said.

Chang noted that in April 2000, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) held a research roundtable on prepubertal bipolar disorder that concluded with general agreement that in children, there exists a“ narrow” bipolar disorder phenotype (bipolar I and bipolar II) based on DSM-IV criteria. The roundtable panelists also concurred on the existence in children of a “broader” phenotype, which they said appears more prevalent than the narrow phenotype, but does not fully meet DSM-IV criteria.

In September 2002, NIMH convened another research roundtable to focus on that broader phenotype, pediatric bipolar-NOS, and to address how the heterogeneous group of children given the diagnosis should be described and studied.

Studies' Value Questioned

Since the 2002 NIMH roundtable, several studies have been published that attempted to better define the presentation of bipolar illness in children. Yet not everyone agrees that those studies have advanced the field.

“Five years ago, pinning down bipolar disorder in children, in particular BP-NOS, was like nailing Jello to the wall,” said Gabrielle Carlson, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and director of child and adolescent psychiatry at Stony Brook University School of Medicine. “Today, we've seen significant advances—we are now nailing cheesecake to the wall.” Carlson served as the discussant for the session Chang chaired at the AACAP meeting.

Researchers have found that children may be more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar-NOS, compared with bipolar I or II, because they commonly do not meet the DSM-IV criteria for a “distinct period” or duration of symptoms, explained Ellen Leibenluft, M.D., chief of the Unit on Affective Disorders in the Pediatrics and Developmental Neuropsychiatry Branch at NIMH, who also participated in the session.

Expansive Mood Not Evident

In addition, Leibenluft said, children rarely display the elevated, expansive mood characteristic of mania in older patients. Instead, the primary symptom is usually significant irritability, “which is much less specific,” she said. “Kids often have frequent, shorter episodes that lead to a sort of chronic presentation where they are [emotionally] labile all the time.”

Following the NIMH roundtables, Leibenluft and her NIMH colleagues published in 2003 a description of an “intermediate phenotype” in addition to the narrow and broad categories already described. The intermediate phenotype included kids who had “clear episodes and hallmark symptoms,” but lasting only one to three days—shorter than required by the DSM-IV criteria. Children who had clear episodes with a marked irritable, but not elevated, mood were also included.

A number of researchers have explored the heritability of bipolar disorder as well, hypothesizing that pediatric bipolar disorder may occur in those children with high genetic risk for the disorder, as evidenced by close adult relatives diagnosed with bipolar I or II.

Eric Youngstrom, Ph.D., an assistant professor of clinical psychology, psychiatry, and management at Case Western Reserve University, said he and his colleagues have followed a cohort of children who have at least one parent with bipolar disorder.

“Kids with a parent who has the disorder are seven times more likely to have bipolar disorder themselves,” Youngstom said, “and are 3.6 times as likely to have any mood disorder.”

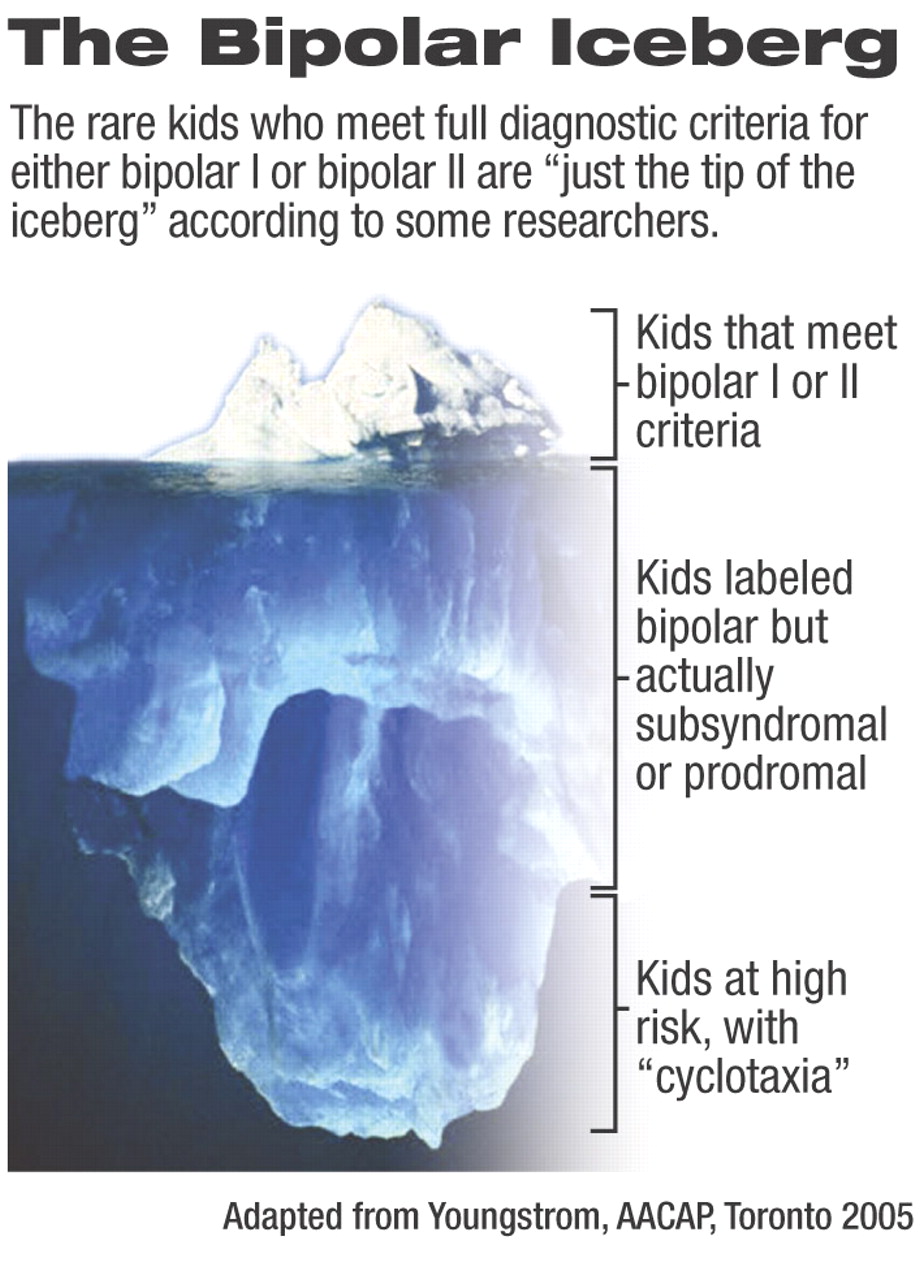

But, Youngstrom noted, these children “are at risk, but not fully syndromal. It's a bit of a fuzzy phenotype.” He and his colleagues are using the term “cyclotaxia” to refer to “a genetic/familial risk for increased depressive symptoms, aggression and mania.”

Those children who fully meet criteria for bipolar I or II are“ really the tip of the mood disorder iceberg,” while those who are subsyndromal and “cyclotaxic” make up the much larger bulk of the iceberg.

However, Carlson was critical of the bipolar heritability studies, noting that so far research has not consistently shown increased occurrence of the disorder in children who are supposed to be at high risk.

“The real difficulty [with bipolar-NOS]” or other labels like“ subsyndromal” or “cyclotaxia,” Carlson commented,“ is we're putting a lot of different definitions into one bucket. And in the real world, children don't simply have bipolar disorder—they have multiple comorbidities.”

Because the field of psychiatry has pursued clinical research based on single diagnoses, Carlson said, rather than symptom clusters or clusters of comorbid disorders, “we don't have a clear picture of the kids included in all of these studies, and so we can't match our patients to [the] findings.” ▪