As happens with many people, reluctance and denial characterized future Miss Rhode Island Aimee Belisle's first foray into treatment for depression.

Belisle's close friend recognized that the irritability, moodiness, fatigue, and loss of appetite Belisle had been experiencing were signs of depression and urged her to make an appointment at the counseling center at Bentley College in Waltham, Mass., where they were both students.

“Basically, I told him I wasn't going to make an appointment right away,” she told Psychiatric News.

So he did what any good friend would do—he picked her up, put her in his car, drove her to the counseling center, and walked in with her.

Belisle, now 24, said she first began experiencing symptoms of depression when she was in high school. “I was crying a great deal and didn't feel excited about anything, even the things I'd previously enjoyed,” she recalled.

“Over time, my symptoms became much worse,” she said. By the time she entered the counseling center for treatment in her junior year, she'd begun cutting herself.

Through the counseling center, she received medications and psychotherapy, and her symptoms began to improve within weeks. Once diagnosed, she decided to educate herself about depression—its prevalence, etiology, and treatment—by researching the topic extensively.

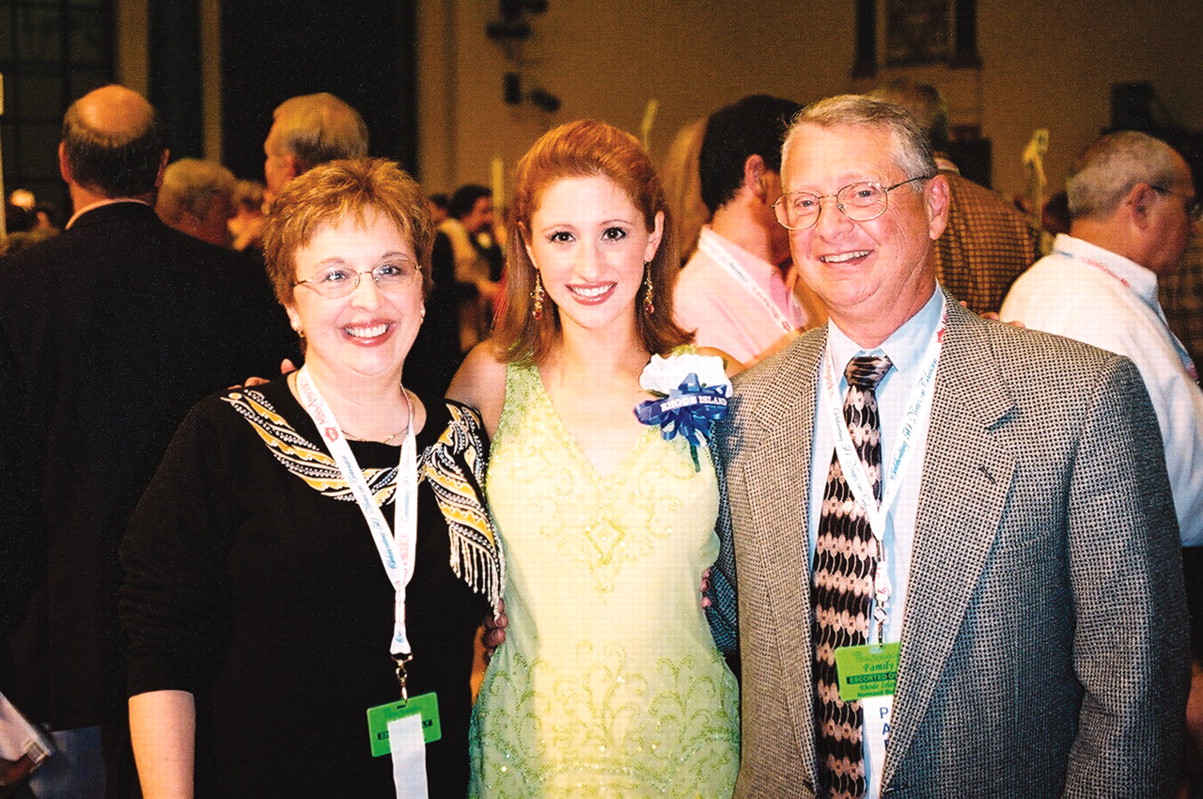

Belisle said she was bolstered by the love and support she received from family and friends and soon learned from her mother that depression ran in the family—her father had been treated for it at different points throughout his life.

Belisle had long aspired to compete in the Miss Rhode Island pageant and decided to enter the competition in part “to show I was able to achieve what I wanted despite having depression,” she said.

She acknowledged that without treatment, “I doubt I would have been able to be focused or clear enough to compete” in the pageant.

When she won the title last year, Belisle decided to make depression awareness her platform. “I wanted my platform to be personal—something I'd experienced myself,” she said.

As part of her platform, she began speaking in public about the need for depression screening in high schools and on college campuses.

Though many were receptive to her message, she encountered ignorance on the part of some. “I've had instances where people would tell me, `You just need to suck it up,'” in regard to her experiences with depression, Belisle said, and she would turn those encounters into opportunities to help others understand that depression isn't something that can be willed away.

It is not uncommon for audience members and others to express their gratitude to Belisle for speaking publicly about depression, she said, which“ convinces me that I'm helping people.”

These days, Belisle divides her time between her job as an auditor and her work as a board member for Families for Depression Awareness, a nonprofit organization established in 2001 to help families recognize and cope with depressive disorders.

She is also a member of APA's newly appointed Presidential Task Force on Mental Health on College Campuses and is working on expanding depression screening and education in high schools and universities in Rhode Island and other states.

“Depression screening is starting to take hold,” she said,“ but is nowhere near as widespread as it should be.”

According to David Fassler, M.D., co-chair of the new task force and a member of APA's Board of Trustees, “Aimee is an eloquent and effective spokesperson on the issue of depression in college students.... She captures her audience by telling her own story in an honest and compelling manner.” ▪