Depression can run in the family, numerous studies have shown. None of these studies, however, has gone beyond two generations, and only a few have had a longitudinal design.

Now a three-generation longitudinal investigation also implies that depression can run in the family.

The investigation was headed by Myrna Weissman, Ph.D., a professor of epidemiology in psychiatry at Columbia University. Study results are reported in the January Archives of General Psychiatry.

In 1982 Weissman and her colleagues selected 47 persons—some of whom had experienced a major depression and others who had not—for a study, then followed the psychiatric fates of those subjects' 86 offspring as they grew older. Then, as the offspring grew up and had 161 children of their own, Weissman and her team tracked their psychiatric outcomes as well. By 2002, the 161 grandchildren were, on average, 12 years of age.

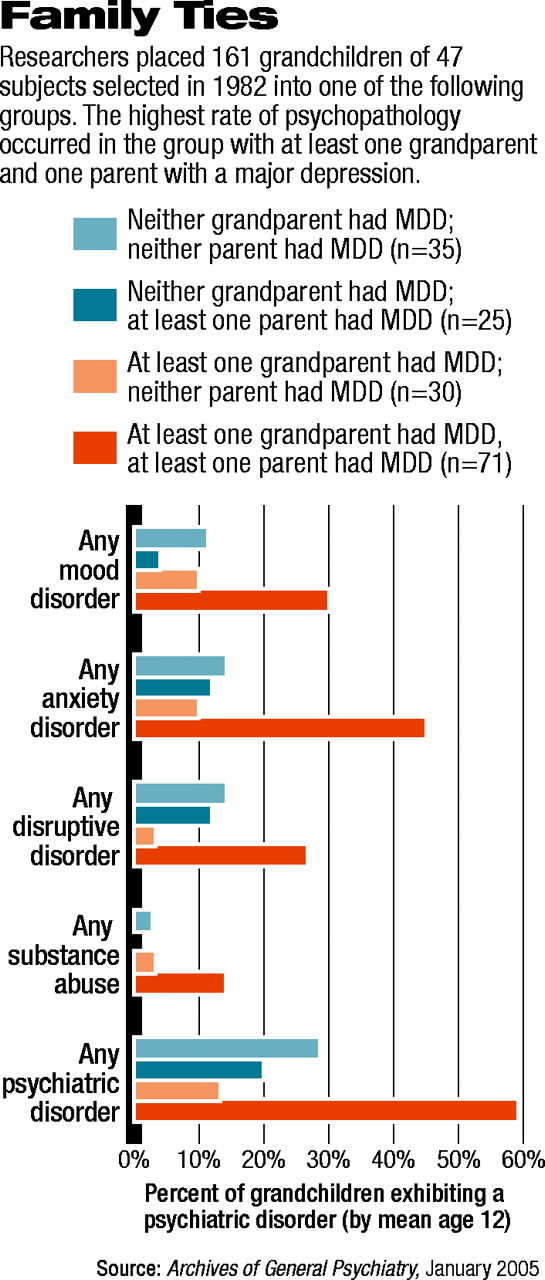

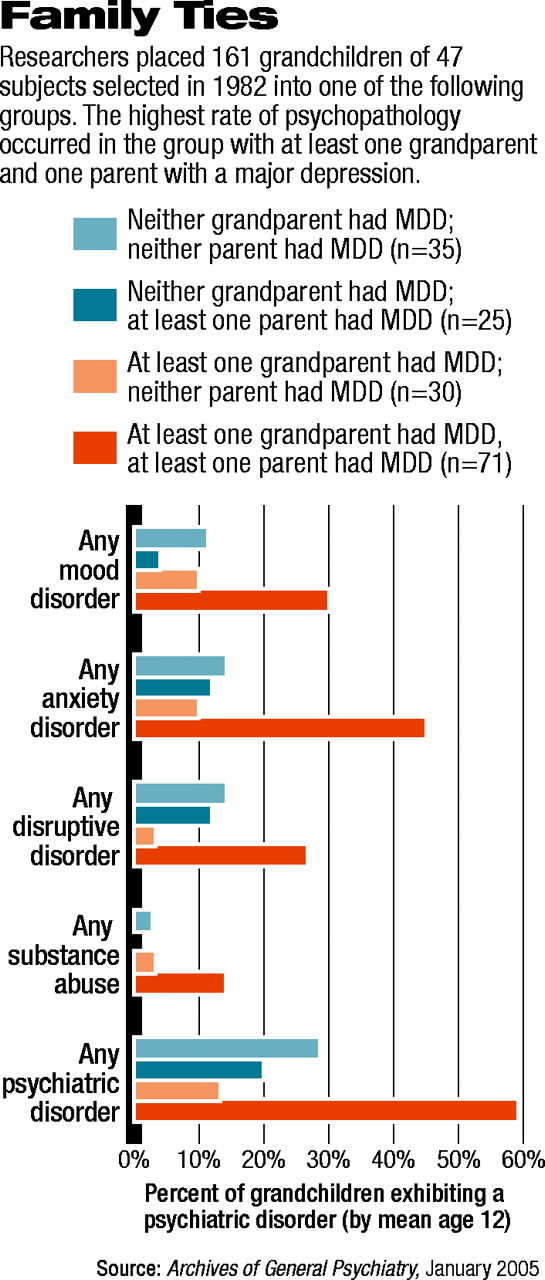

The researchers then divided these 161 youngsters into four groups—those with at least one grandparent and at least one parent who had experienced a major depression (71); those with at least one grandparent who had experienced a major depression but with no parent who had (30); those with no grandparent who had experienced a major depression, but with at least one parent who had experienced one (25); and those who had neither a grandparent nor a parent who had experienced a major depression (35). Grandchildren with at least one grandparent and at least one parent who had experienced a major depression had the highest rate of psychopathology, with 59 percent having at least one psychiatric disorder.

In contrast, grandchildren with at least one grandparent—but no parent—who had experienced a major depression had the lowest rate of psychopathology, with 13 percent having at least one psychiatric disorder.

The other two groups fell between those two. Psychiatric disorders were identified in 20 percent of grandchildren who had no grandparent who had experienced a major depression, but at least one parent who had. And 29 percent of grandchildren with neither a grandparent nor a parent who had experienced a major depression had at least one psychiatric disorder.

Moreover, when the scientists compared grandchildren who had a grandparent with a history of major depression and a parent with a history of severe major depression with grandchildren who had a grandparent with a history of major depression and a parent with less-debilitating major depression, 68 percent of the former had at least one psychiatric disorder, whereas only 31 percent of the latter did, a highly significant difference.

These results have clinical implications, the researchers said in their study report: “Obtaining family history of depression and its severity and impairment in previous generations should help to identify persons at high risk for psychopathology at a young age.”

Another noteworthy finding from the study was that anxiety disorders, not depressive disorders, were the principal psychiatric disturbance experienced by grandchildren who had at least one grandparent and parent with a history of depression. Other studies have shown that anxiety disorders in childhood often precede depression in adolescence and young adulthood. Thus anxiety in these grandchildren may herald later risk for depression, Weissman and her colleagues wrote, and treatment of such anxiety might protect them from the later development of depression.

In fact, as Weissman told Psychiatric News, they are considering conducting a study to see whether treating anxiety in children from families at high risk of depression might prevent the onset of major depression later.

“Nothing in these findings was surprising,” Neal Ryan, M.D., a professor of child psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview. “I think they extend what we have seen so far...[But] this is a uniquely valuable study because of the very long period of follow-up of these families, which now extends into the third generation.... [Also] the earlier findings of this series of studies has very well withstood the test of time.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005 62 29