A pair of recent studies have independently come to the same conclusion on the relationship between antidepressant prescribing and suicide rates. As prescribing of medications—especially newer antidepressants—increases, suicide rates go down.

Researchers at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine and the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute completed an extensive review of data and literature and concluded that suicide rates have declined steadily since the introduction of newer reuptake inhibitor antidepressants in 1988. While not proof, they said, the data strongly suggest that a direct relationship exists and that most persons who did commit suicide did so because of untreated mental illness.

In another analysis, researchers at the Center for Health Statistics at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute determined that increases in prescriptions for SSRIs and other newer atypical antidepressants are associated with lower suicide rates on a county-by-county basis across the United States.

The intricate analysis of National Vital Statistics data, provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, linked that county-level suicide data to county-level antidepressant prescribing data from IMS Health Inc., a company that tracks prescription data worldwide.

The UIC/Columbia group concluded that “lower suicide rates both between and within counties over time may reflect antidepressant efficacy, compliance, a better quality of mental health care, and low toxicity in the event of a suicide attempt by overdose.”

Untreated Depression at Fault

“Our findings strongly suggest that... individuals who committed suicide [while prescribed an antidepressant] were not reacting to their SSRI medication,” Julio Licinio, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and endocrinology at UCLA and the lead author of the UCLA study, said in a written statement. “They actually killed themselves due to untreated depression.”

The analysis, funded by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the Dana Foundation, appeared in the February Nature Reviews Drug Discovery.

“The recent debate has focused solely on a possible link between antidepressant use and suicide risk, without examining the question within a broader historical and medical context,” Licinio explained. “We feared that the absence of treatment may prove more harmful to depressed individuals than the effects of the drugs themselves.”

Licinio and his colleague, Ma-Ling Wong, M.D., who are co-directors of the Center for Pharmacogenomics and Clinical Pharmacology at the Neuropsychiatric Institute, conducted an extensive database search of studies published between 1960 and 2004 on antidepressants and suicide. The resulting list of studies ranged from population-based analyses of nearly 160,000 patients exposed to multiple antidepressants to smaller clinical trials involving one drug and only several hundred patients.

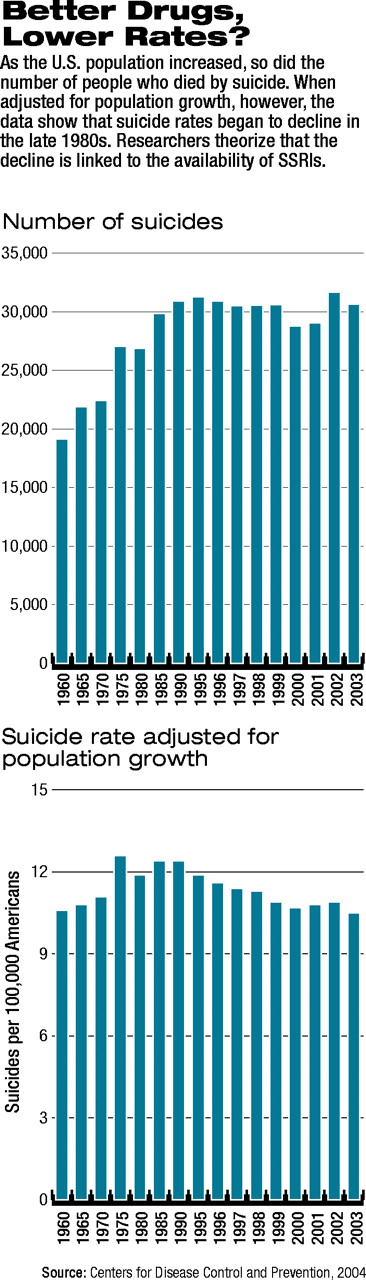

The researchers then developed a comprehensive timeline of key regulatory events relating to the medications. They also generated charts tracking antidepressant use and suicide rates in the United States.

Licinio said they were surprised by what they found.

“Suicide rates rose steadily from 1960 to 1988, when Prozac [fluoxetine], the first SSRI drug, was introduced,” he said.“ Since then, suicide rates have dropped precipitously, sliding from the eighth to the 11th leading cause of death in the United States.”

Intriguingly, while the actual numbers of suicides steadily increased from 1960 until the late 1980s and then leveled off, the suicide rate (per 100,000 population) rose between 1960 and the 1970s. Suicide rates peaked in the early 1970s and then fluctuated until the late 1980s, when they began a steady decline (see charts at right).

Licinio added that the pair reviewed several large European and U.S. reports in which “researchers found blood antidepressant levels in less than 20 percent of suicide cases.” This, Licinio said, implies that the vast majority of suicide victims either never received treatment or were not compliant with prescribed treatment at the time of their deaths.

Second Study, Similar Results

The second recent analysis, led by Robert Gibbons, Ph.D., of UIC's Center for Health Statistics, and suicide researcher J. John Mann, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Columbia and chief of psychiatric research at New York State Psychiatric Institute, was published in the February Archives of General Psychiatry.

Their analysis was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, with the assistance of a grant in aid from Pfizer Inc., to purchase prescription data from IMS Health.

Gibbons and Mann found that, overall, there was no significant relationship between antidepressant medications and suicide rates. However, within classes of antidepressants, SSRIs and newer atypical antidepressants were associated with lower suicide rates. In comparison, they found a significant association between higher rates of prescribing for older, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and higher rates of suicide. In their analysis they adjusted for age, sex, race, income, and county-to-county variability in suicide rates.

Even after adjustment, the relationship between TCAs and higher rates of suicide persisted, leading Gibbons and Mann to suggest that “a high relative prescription rate of TCAs is not simply an indicator of limited access to quality mental health care, but indicative that choice of treatment matters.”

The UIC/Columbia team said that their results, along with several previous studies, indicate that “suicidal behavior correlates with inadequate prescription of antidepressants, and from 1978 to 1997, the proportion of the outpatient U.S. population with depression that received at least one antidepressant prescription increased from 37.3 percent to 74.5 percent.”

Mood disorders, they noted, accounted for 45 percent of antidepressant prescriptions in 1997 and 59 percent by 2000. “So, both the proportion and therefore the impact of more prescriptions on mood disorders are likely to have been sustained over this limited period of time for which we have data.”

Limitations Identified

The authors of both reports assessed the limitations of the databases with which they worked. Medication-usage estimates based on outpatient data are simply estimates, they noted, and suicide data are affected by variables such as suicide definition, qualifications of medical examiners, and whether all suspected suicide deaths in a particular population were investigated. Numerous variables also interact in clinical trial data, and any conclusions regarding suicidal or harmful thoughts or behaviors tied to antidepressants in clinical trials have been subjected to numerous questions (see related article on

page 1).

Yet these independently completed studies came to similar conclusions. In particular, said Gibbons and Mann, “despite potential variability, strong associations between antidepressant prescription rates and suicide rates were observed. Since the associations were in opposite directions for TCAs versus SSRIs and newer non-SSRIs, this variability is not producing systematic bias.”

What is clear, the UIC/Columbia team concluded, is that “the findings of this study relate to associations in the data and not to causation. Randomized, controlled trials in high-risk patients are still needed.”

An abstract of “Depression, Antidepressants, and Suicidality: A Critical Appraisal” is posted online at<www.nature.com/cgi-taf/DynaPage.taf?file=/nrd/journal/v4/n2/abs/nrd1634—fs.html>. An abstract of “The Relationship Between Antidepressant Medication Use and Rate of Suicide” is posted at<http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/62/2/165>.▪

Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005 62 165