So there they are, “Tom” and “Tara,” sitting on their back porch and lighting up their first cigarettes of the day. The mellow sun rays and fresh morning breeze are forgotten as the nicotine and other chemicals in the cigarettes turbocharge their brains.

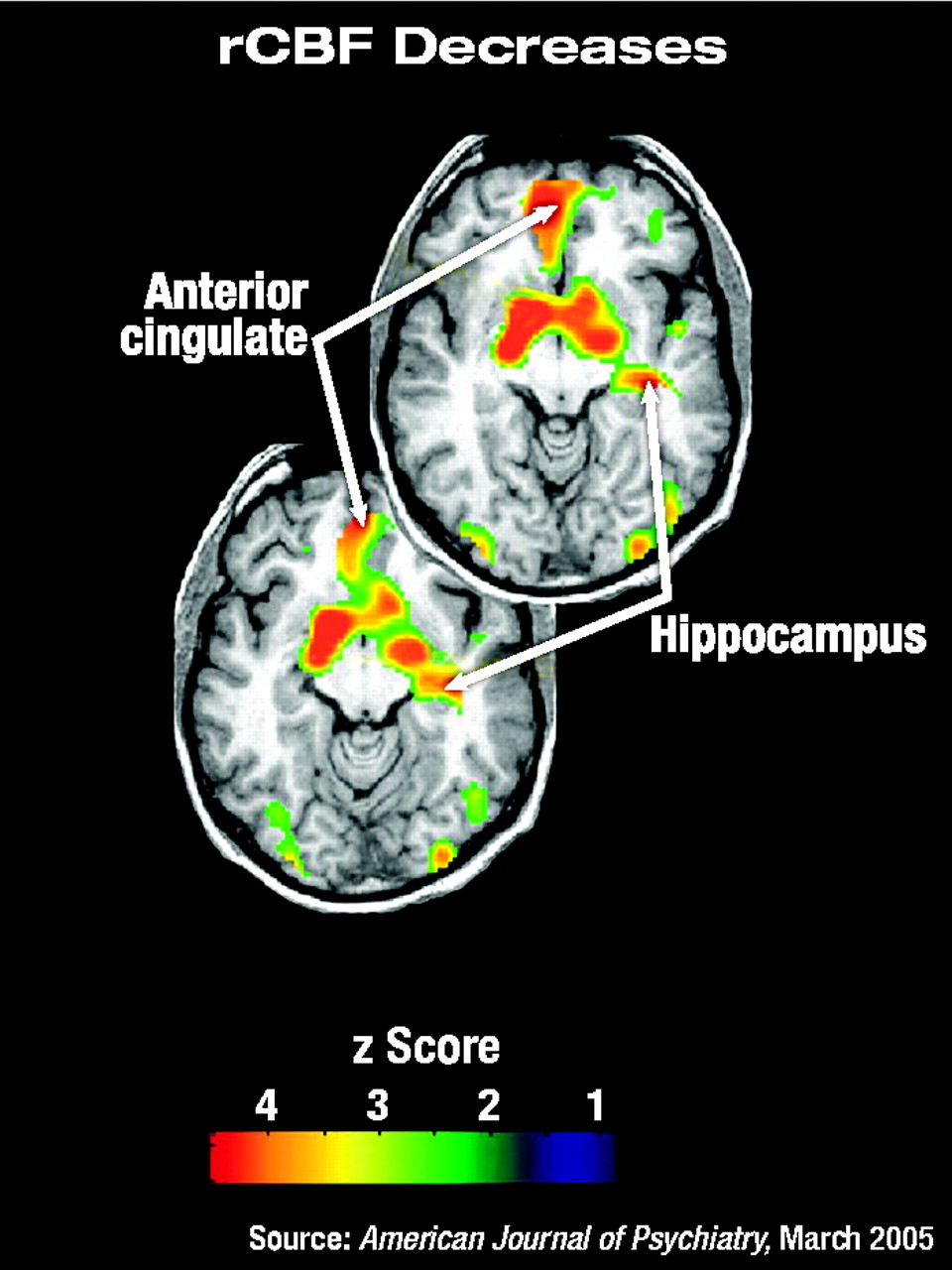

Blood rushes to the visual cortex and cerebellum, blood flowing to the anterior cingulate and right hippocampus declines, and as blood flow to the latter two regions ebbs, Tom's and Tara's craving for a cigarette is snuffed out as well.

This anecdote illustrates the outcome of a study exploring the brain impact of the first smoke of the day. The study was headed by Jon-Kar Zubieta, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan. Findings appeared in the March American Journal of Psychiatry.

Nineteen cigarette smokers who smoked seven to 30 cigarettes a day for seven years on average were selected to participate in the study. On the night before the study, they abstained from smoking, then reported the next morning to the hospital's positron emission tomography (PET) suite. In the suite, PET scans tracked blood flow to various parts of their brains, and they were asked to rate, on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 10 (most ever), how they felt regarding cigarette craving. Then they lit up their first cigarettes of the day. Once again PET scans were used to track blood flow to various parts of their brains, and once again subjects were asked to rate how they felt regarding cigarette craving.

Subjects' baseline PET scan results and craving reports were then compared with their PET scan results and craving reports after lighting up.

The first smoke, Zubieta and his colleagues learned, resulted in increases in blood flow to two regions located in the back of the brain—the visual cortex and the cerebellum—and in decreases in blood flow to a region located in the front of the brain and in another region located in the midbrain—the anterior cingulate and right hippocampus, respectively.

Of course, the visual cortex is crucial for vision; the cerebellum for movement; the anterior cingulate for motivation, executive control, and decision making; and the hippocampus for memory and emotion. But the anterior cingulate has also been implicated in drug craving, and the hippocampus in associating drugs with certain environmental cues. Even more noteworthy, the researchers found, as blood flow to subjects' anterior cingulate and right hippocampus ebbed, their craving for a cigarette diminished proportionally.

Thus, both the anterior cingulate and the right hippocampus “seem quite involved in the [cigarette] addiction process,” Zubieta said in an interview. And when smokers have not used nicotine for a while, the left anterior cingulate and the right hippocampus “may actually be overactivated, only going down in their function after receiving a nicotine `fix.'”

The implication of these findings for cigarette smokers, Zubieta added, is that cigarette smoking is simply another form of drug addiction—in fact, the most frequent form of substance abuse.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Am J Psychiatry 2005 162 567