Depressed patients with heart disease are less likely to take their antidepressants and less likely to take their heart or diabetes drugs than are nondepressed patients, according to two recent studies.

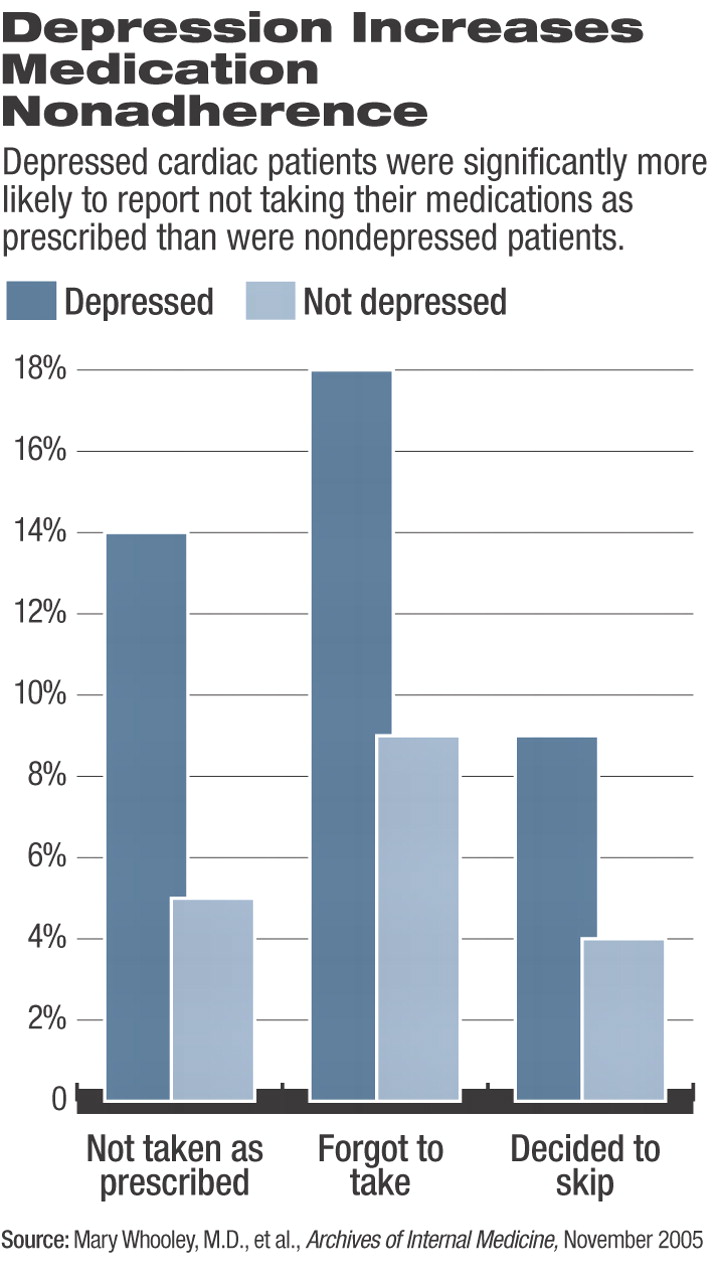

The first study found that patients with severe depressive symptoms were 2.2 times more likely than those with no or minimal symptoms to forget to take their medicines, intentionally skip them, or not take them as prescribed, according to Mary Whooley, M.D., an associate professor of medicine, epidemiology, and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

Their research was part of the Heart and Soul Study and included 940 patients, of whom 204 were diagnosed with major depression.

“We found that depression was associated with medication nonadherence even after correction for differences in angina frequency and history of revascularization between depressed and nondepressed patients,” the researchers wrote in the November 28, 2005, Archives of Internal Medicine. The association occurred only among patients taking beta-blockers but not among those who were not taking that cardiovascular drug. The Heart and Soul Study is a prospective cohort study of psychosocial factors and health outcomes in 1,024 patients with coronary heart disease.

The second study, by Elaine Chiao, Pharm.D., of Applied Health Outcomes in Palm Harbor, Fla., and colleagues, used pharmacy claims and medical-charges data from a sample of 8,040 patients in the National Managed Care Benchmark Database, which draws data from 30 health plans in the United States.

All the patients had filled prescriptions for antidepressants, although not all had been diagnosed with anxiety or depression, wrote Chiao. Of those prescribed an antidepressant, only 40 percent took their medications.

All of the patients had also been diagnosed with and prescribed drugs for coronary artery disease and dyslipidemia, or diabetes, or a combination of those three disorders.

During the six months leading up to starting antidepressant medications, 75 percent were adherent to these comorbid cardiovascular disease medications. In the six months following the index date, patients adherent to antidepressant medication were also more likely to take their comorbid disease medication than were patients who weren't taking their antidepressants.

In fact, wrote Chiao and colleagues, “[I]n patients treated with antidepressant agents, improved antidepressant drug adherence is associated with an almost two-fold improvement in comorbid disease medications adherence.”

Patients sticking to their antidepressant regimen also demonstrated a 6 percent to 20 percent reduction in medical charges over the course of one year of follow up, mostly resulting from lower inpatient and outpatient charges.

Patients in this study with coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia, or diabetes would incur $1,230 less in charges a year if they remained on their antidepressant medications. Improved adherence might initially raise total prescription costs, but the increase would be offset by reduced costs related to the comorbid illnesses and to overall medical care, suggested Chiao.

Both studies have their limitations but do not arrive in a vacuum, said John Rumsfeld, M.D., Ph.D., a staff cardiologist at the Denver VA Medical Center and associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center. The cross-sectional Heart and Soul Study cannot demonstrate causation, and Chiao's article reports retrospective claims data, but is not a prospective, controlled trial.

“If these were the only two studies we had, they would be considered interesting but preliminary,” said Rumsfeld in an interview. “But they join a large body of epidemiological evidence that depressed patients don't adhere to their medications.”

Rumsfeld has collaborated with Whooley in the past but was not a coauthor of the current paper. Cardiologists recognize perhaps one-fourth of the cases of depression among their patients and treat barely half of that number, he said.

Both biological and behavioral connections between heart disease and depression have been suggested. Depression increases sympathetic nervous tone, platelet aggregation, and norepinephrine levels. Depressed patients are also often more hopeless, lack energy and focus, or may be more sensitive to adverse effects of drugs, any of which may affect patients' willingness to take medications, Whooley noted.

Some combination of these effects may be at work to lower adherence among users of beta-blockers, which are prescribed for many heart patients. Those drugs often cause fatigue, which can be confused with depression and reduce compliance even further, said Rumsfeld. That raises a chicken-and-egg problem.

“If we want them to take beta-blockers, we're probably going to have to treat their depression first,” he said.

The time has arrived for researchers to move beyond epidemiology and retrospective studies and conduct full-fledged intervention trials to convince cardiologists that depression is a serious comorbidity, said Rumsfeld.“ If this were a new blood test, cardiologists would all be paying attention.”

Yet so far there's been no such groundswell, and the “epidemic” of underrecognized and undertreated depression among heart patients continues, he said. “Cardiologists will have to diagnose and treat depression for cardiovascular reasons.”

Whooley's study was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, American Federation for Aging Research, and Nancy Kirwan Heart Research Fund. Chiao's study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Arch Intern Med 2005 165 2508

Arch Intern Med 2005 165 2497