More than 1,000 Mennonite conscientious objectors performed public service work in the nation's public mental hospitals during the war, substituting for male employees who left for military service.

The conditions they observed in state mental hospitals impelled many young Mennonites to work for change in the public system and to help create the Mennonites' own mental health system. Three of the Mennonite Civilian Public Service (CPS) men now living in Pennsylvania recounted their stories to Psychiatric News.

Jacob Harnly lived in Manheim, Pa., the son of a meatcutter. “I grew up in a Mennonite background, and pacifism was part of our religious philosophy.”

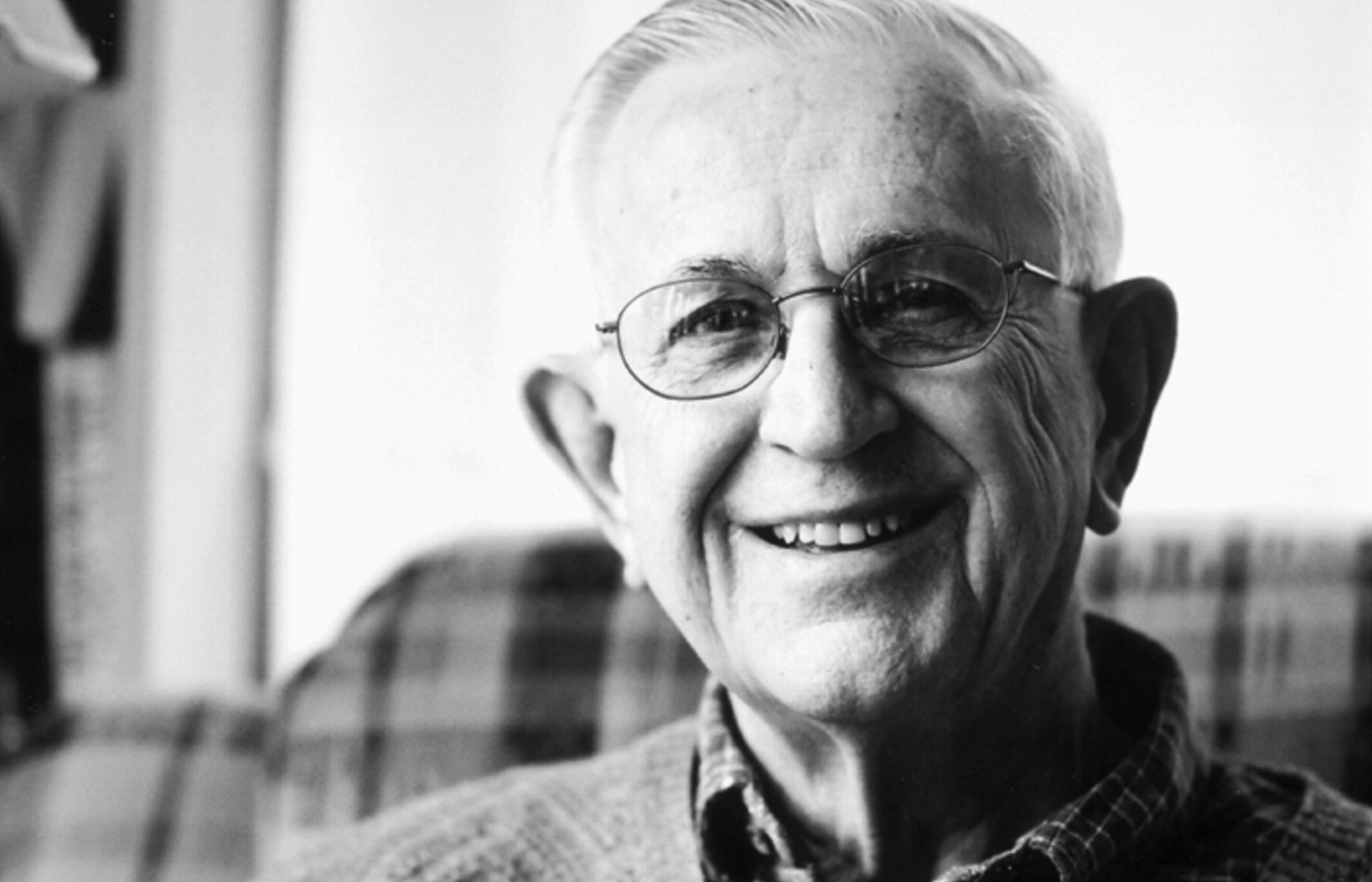

The same philosophy animated others as well. When the 100 young men at their draft physical in Harrisburg, Pa., in February 1943 were asked who among them would not serve in the army, only one, Frank Shirk, stepped forward.

Richard Lehman was born in Lancaster, Pa., in 1926 and worked in an auto-parts store before he was drafted in 1944.

“I had a normal childhood. I played baseball with the neighborhood boys, but they knew I was different,” said Lehman, speaking of his Mennonite upbringing. “We went against the culture of our times. Maybe God made us different. Pacifism was the baggage our shoulders had to carry.”

Lehman worked on soil conservation projects, as did Harnly and Shirk, and then fought forest fires in Montana. After that, he spent six months as a ward attendant at Greystone State Hospital in New Jersey. Once, another CPS man took him to the main building at Greystone, past patients in cages.“ Watch out,” the man told him. “Don't get too close—they might throw feces.”

“We thought we should be doing something more beneficial to society than conservation work while others were overseas giving their lives,” said Harnly. In November 1943 he went to Marlboro State Hospital in New Jersey and served on a ward housing men with mental illnesses as well as other medical conditions.

“First you had to get used to the odors,” he recalled.“ Then the goal was to have as many people doing useful things around the cottage, to keep them active, a kind of occupational therapy. A lot went out to work in the dairy, some in the vegetable garden, some in the orchard.”

He helped give patients electroshock therapy. One man held each arm and leg of the patient. “It was a frightening experience for us and for the patients,” he said.

In spring 1945, Shirk joined a group of 30 CPS men who went to Hudson State Hospital in New York, home to 5,000 mental patients. Training?“ Absolutely zero. We learned on the job. Most patients sat or walked around in a big room with benches. There was another room, maybe 12 feet by 12 feet, with 15 guys completely naked. Two or three window panes were broken out too. The first thing we did was ask to have the windows replaced and find clothes for the patients. We cleaned them up and dressed them. If they soiled themselves, we cleaned them up again and gave them clean clothes.”

One day several CPS men reported that some attendants had beaten a patient, Shirk remembered. The hospital superintendent investigated and fired the offenders. Since two were veterans, the dismissals created resentment on the part of employees and their supporters in the nearby town. Local educators and clergy helped defuse the situation, however, and the episode resulted in a closer working relationship between the CPS team and the superintendent.

“When we left and went back home, we had a whole different perspective on what was going on in mental hospitals,” said Harnly.“ Many of us were anxious to see changes made. So the Mennonite Central Committee started hospitals. I think progress has been made in mental health, and I feel good that I could help turn that around a little bit.”▪