Arecent study counters previous research that found patients of psychiatrists were more likely to receive psychotherapy from another type of clinician.

The authors attributed the finding to the nature of the study, which randomly sampled all U.S. psychiatrists. The previous research focused on psychiatrists in organized settings, which have more associated support personnel than most private practices.

“In group settings psychiatrists are leaned on for their medical management and major case evaluation skills, which require a physician's knowledge,” said Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., one of the study's authors. Regier is director of APA's Office of Research and the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education (APIRE).

The results were based on the survey responses of 587 psychiatrists who participated in APIRE's 1999 study of psychiatric patients and treatments. The study included nationally representative data for 1,589 adult patients.

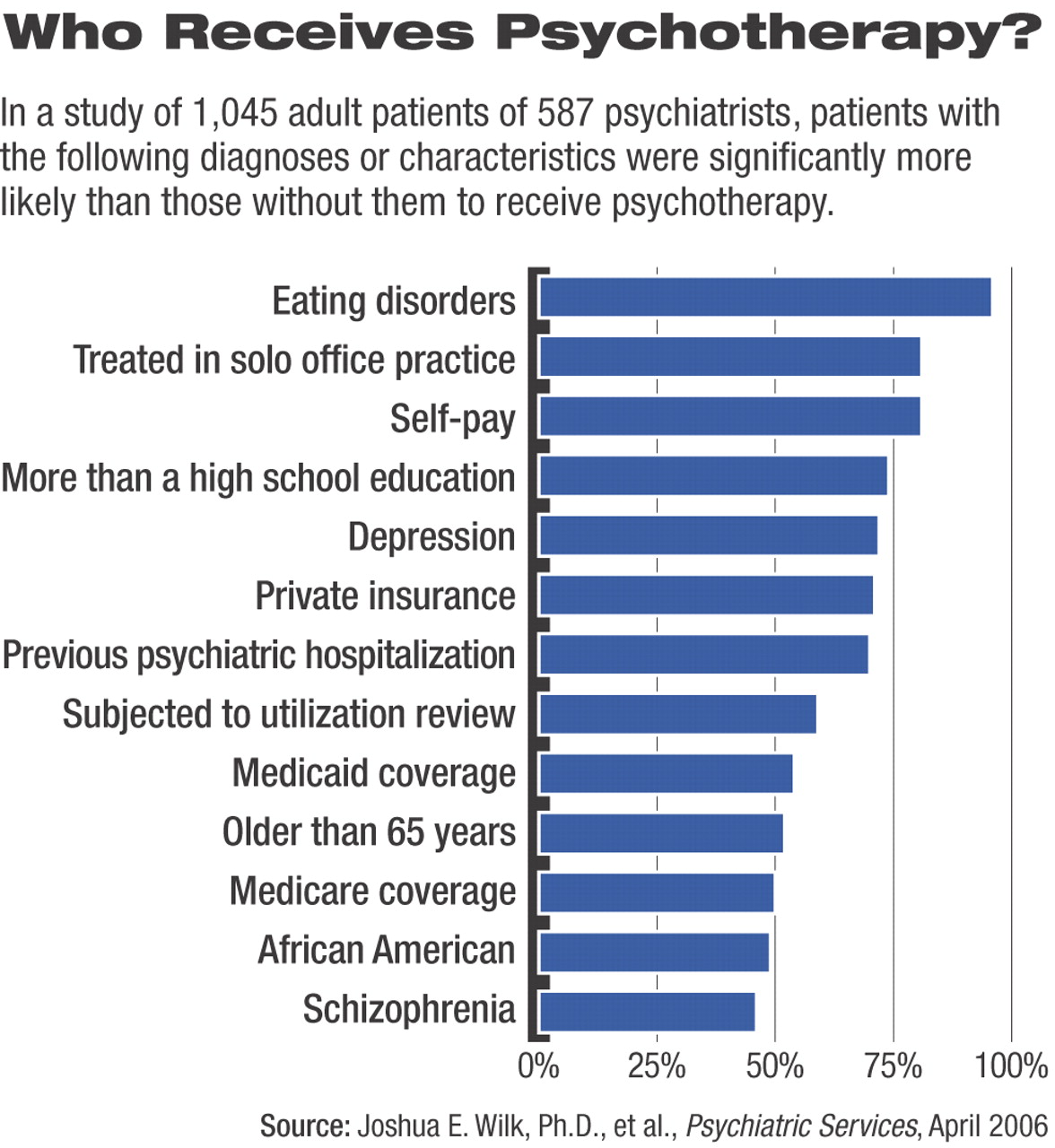

The survey results indicated that patients with more severe psychotic symptoms were less likely than those with mild to moderate psychotic symptoms to receive psychotherapy. Although 72 percent of patients with depression received psychotherapy, most with schizophrenia did not. Major depression was the most common primary diagnosis in the sample (39 percent of patients), while schizophrenia was the second most common (16 percent).

The results, Regier said, indicate psychiatrists need to form better linkages with other professions to provide patients with quality care.

“It is clearly indicated in our guidelines that social-skills training and family-skills training in addition to psychotherapy are essential for optimal treatment of these severe disorders,” Regier said.“ These kinds of therapy resources are not readily available in a private-practice psychiatrist's office. So to get them, the psychiatrist has to establish consultation relationships with facilities that can provide that intensive kind of care to the severely mentally ill.”

The study identified a decrease in the amount of psychotherapy psychiatrists provide in relation to the increased amount of drug therapy they provide and found that this practice was especially pronounced among psychiatrists practicing within a managed care system.

The cost-review process of managed care, Regier said, increasingly identifies medication treatment as more cost-effective, so the economics of reimbursement may push psychiatrists to focus on evaluation and drug therapy over psychotherapy. Previous research has shown that patients who receive drug therapy and psychotherapy from a psychiatrist may benefit from the physician's ability to track more closely and evaluate the effects of the medication on them.

“Although the financing system is clearly driving people away from therapy, I wonder if it is truly cost-effective over the long term to do that,” Regier said.

The study also found that patients who used private insurance or self-pay were much more likely to receive psychotherapy than Medicare and Medicaid recipients. Eighty-one percent of patients who self-pay and 71 percent of those with private insurance received therapy compared with 54 percent of Medicaid and 50 percent of Medicare recipients.

Studies have tracked a decrease in the use of psychotherapy since 1985 by office-based psychiatrists and mental health profesionals who provide outpatient treatment. The increase in pharmacological options and a greater acceptance of drug treatments by the public may also encourage this trend, the study authors concluded.

Psychiatrists indicated that the therapeutic techniques they used most often were the discussion of medication management issues (81 percent of respondents), discussion of current relationships (77 percent), and education of the patients about their illness (68 percent).

More long-term research is needed, said Regier and his colleagues, to identify the long-term impact of reduced use of psychotherapy and to assess the impact of the different types of therapy that are utilized.