Although scientists have long demonstrated that various medical illnesses can be prevented by vaccines, early-screening tools, or particular behaviors, they have only recently started conducting studies to see whether mental illnesses can be prevented by specific tactics.

In the past decade, for example, trials have been launched to see whether improved childhood nutrition prevents antisocial behavior, whether drug treatment prevents schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in young people at high risk, and whether an Air Force suicide prevention program is effective. The latter, in fact, has already produced positive results (Psychiatric News, December 17, 2004). And now three more studies on preventing mental illness have produced positive findings as well.

Depression Thwarted

The purpose of the first study, conducted by Filip Smit and other prevention researchers at Trimbos Institute in Utrecht, the Netherlands, was to see whether a brief intervention could keep primary care patients on the brink of a clinical depression from developing the disorder.

Some 200 primary care patients with subthreshold depression were randomly assigned to receive either care as usual by a general practitioner or care as usual by a general practitioner plus an experimental intervention. The intervention consisted of giving a patient a self-help manual on how to manage moods as well as six brief phone conversations with a “prevention” worker on how to apply techniques described in the manual.

A year later, 18 percent of the control group had developed a DSM-IV Axis I depression, compared with only 12 percent of the experimental group—a statistically significant difference, the researchers reported in the April British Journal of Psychiatry.

“This represents reduction in the incidence by a third,” they wrote, “and indicates superior effectivenss of adjunctive minimal-contact psychotherapy compared with care as usual.”

Moreover, “not only is the intervention more effective,” but economic evaluation indicated that “choosing it over usual care alone is likely to be the best treatment option...,” the investigators pointed out.

Behavior Problems Reduced

The second study was conducted by Mark Greenberg, Ph.D., director of the Prevention Research Center at the Pennsylvania State University, and co-workers to see whether a school-based learning program called the PATHS Curriculum could prevent internalizing or externalizing behavior problems. The PATHS Curriculum is designed to help children aged 4 to 11 acquire social and emotional competence by practicing various self-control strategies.

More than 300 second- and third-grade children were randomized to receive either regular school instruction or regular school instruction plus the PATHS Curriculum. They were assessed at the start of the study, seven months after the curriculum had ended, and a year after the curriculum had ended.

At seven months after the assessment, there were significantly greater improvements in both inhibitory control and in verbal fluency among the intervention children than among controls, the researchers found. A year after the assessment, the intervention children were found to have fewer internalizing-behavior and externalizing-behavior problems than the control children. Moreover, improvements in externalizing problems were found to be mediated via greater inhibitory control, and improvements in internalizing problems were found to be mediated via both greater inhibitory control and greater verbal fluency.

Greenberg reported these results at a recent child-resiliency conference sponsored by the New York Academy of Sciences and held in Arlington, Va.

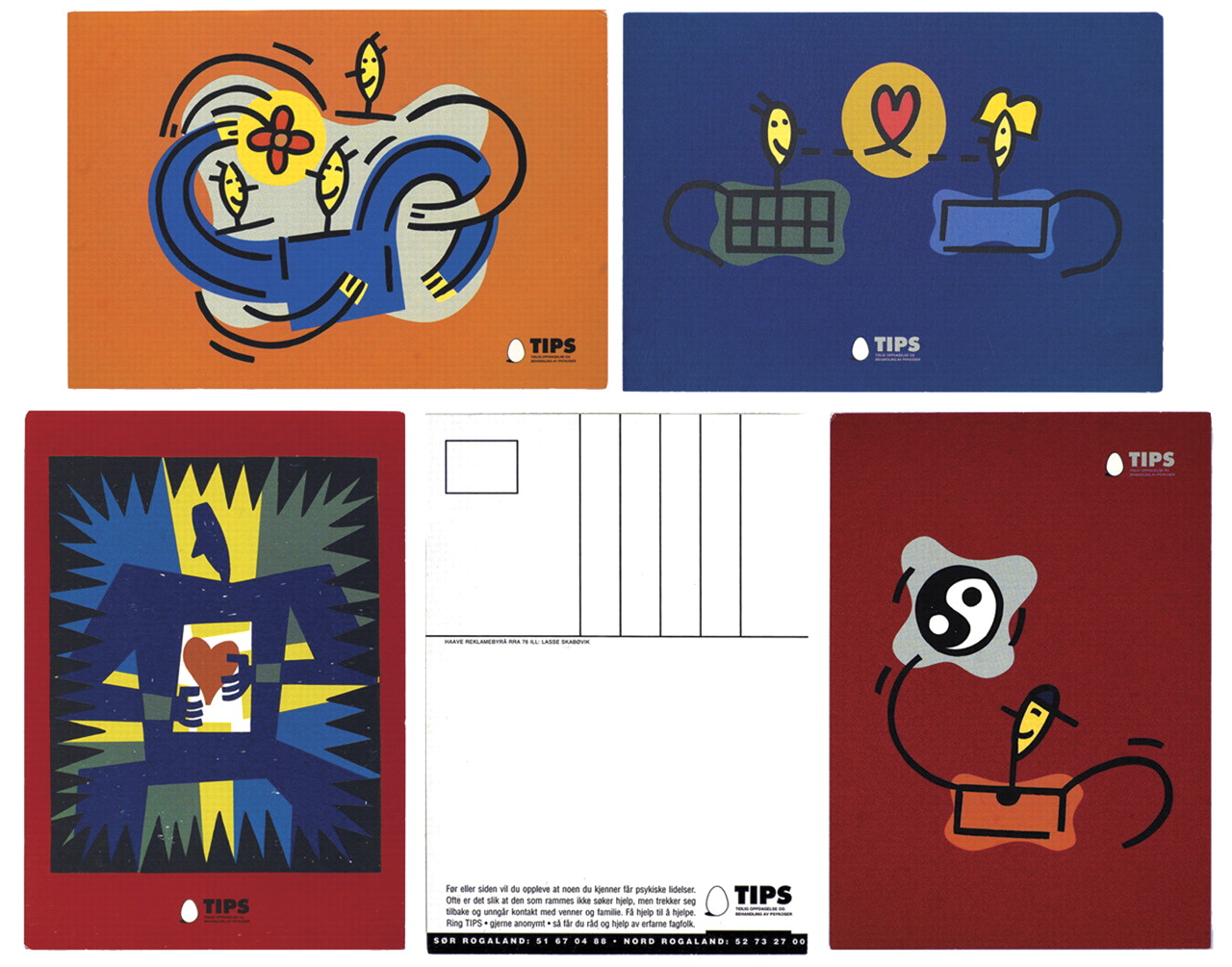

The third study, headed by Ingrid Melle, M.D., Ph.D., of Ulleval University Hospital in Oslo, Norway, focused on preventing suicide in individuals in the early stages of schizophrenia since suicide risk in such persons has been found to be quite high.

Melle and her coworkers designed their investigation to test this hypothesis: If the public were made more aware of the symptoms of early schizophrenia through a media/education campaign and of the value of treating it at an early stage, would it bring people in the early stages of schizophrenia into treatment sooner and thereby reduce their risk of suicide?

Such an educational campaign was then conducted in two communities, while two other communities served as controls. Individuals in the four communities who sought first-time treatment for schizophrenia during the campaign as well as during the next four years were then identified, and 281 of them were enrolled in the study. Half came from the communities that had conducted the campaign, the other half from the communities that had not.

Melle and her colleagues then assessed the number of suicidal thoughts and behaviors occurring in the month before seeking treatment in both groups. The exposure group had experienced significantly fewer suicidal thoughts and behaviors in the month before seeking treatment than the nonexposure group had, the researchers found. By getting treatment earlier, they reduced their risk of suicide, Melle and her team concluded in the May American Journal of Psychiatry.