The quality and intensity of care provided to chronically ill, elderly patients varies widely from region to region, with hospitals that provide the most intense and costly care frequently reporting poorer outcomes.

The finding points to continuing problems with quality of care and unnecessary spending in Medicare, said John Wennberg, M.D., M.P.H., and colleagues who wrote a new report by the Dartmouth Atlas Project.

It also underscores the idea that “more care is not always better care”—a maxim that is honored far more in the breach than in the observance, they said.

“Variation is the result of an unmanaged supply of resources, limited evidence about what kind of care really contributes to the health and longevity of the chronically ill, and falsely optimistic assumptions about the benefits of more aggressive treatment of people who are severely ill with medical conditions that must be managed but can't be cured,” Wennberg said in a statement accompanying the report, “The Care of Patients With Severe Chronic Illness: An Online Report on the Medicare Program.”

Wennberg and colleagues studied the records of 4.7 million Medicare enrollees who died from 2000 to 2003 and had at least one of 12 chronic illnesses: cancer, lymphoma or leukemia, chronic pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, severe chronic liver disease, diabetes with organ damage, chronic renal failure, nutritional deficiencies, dementia, or functional impairment.

“The extra spending, resources, physician visits, hospitalizations, and diagnostic tests provided in high-spending states, regions, and hospitals don't buy longer life or better quality of life.”

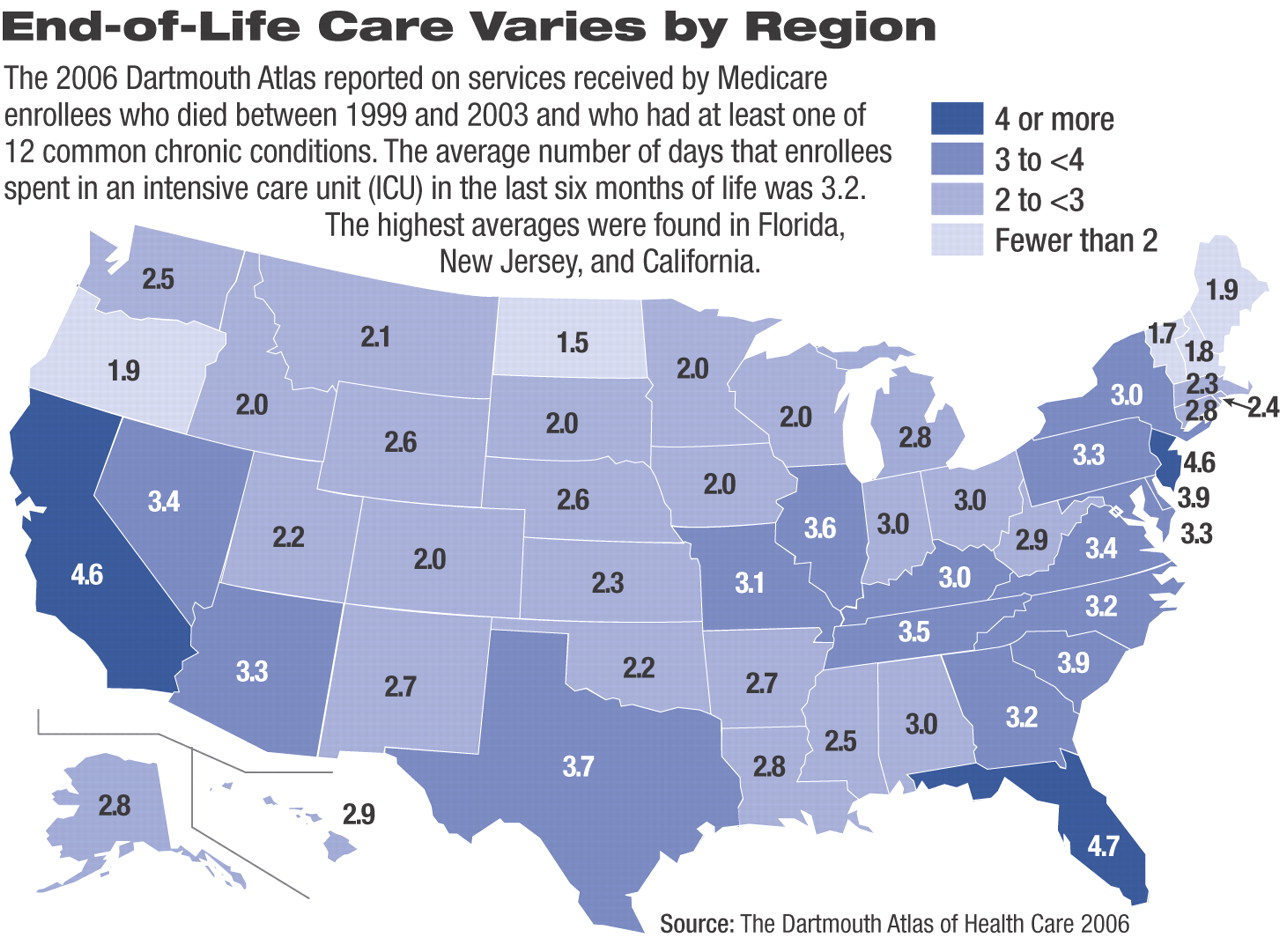

They found that among people who died between 1999 and 2003, per capita spending varied by a factor of 6 among hospitals across the country. Average utilization and spending varied from state to state, from region to region within states, and from hospital to hospital within the same regions (see map).

Spending was not correlated with rates of illness in different parts of the country; rather, it reflected how intensively certain resources—acute-care hospital beds, specialist physician visits, tests, and other services—were used in the management of people who were very ill but could not be cured, according to the report.

“The extra spending, resources, physician visits, hospitalizations, and diagnostic tests provided in high-spending states, regions, and hospitals don't buy longer life or better quality of life,” the authors noted.“ In fact, those with chronic illnesses who live in high-rate regions have slightly shorter life expectancies and less satisfaction with their care than those in regions with lower rates of spending. When it comes to managing chronic illnesses, greater use of hospitals and physician labor doesn't result in additional health; the problem is waste and overuse in high-rate states, regions, and hospitals, not underuse and health-care rationing in low-rate areas and institutions.”

For instance, the report found that patients in low-cost, high-quality regions such as Salt Lake City, Rochester, Minn., and Portland, Ore., are admitted less frequently to hospitals, spend less time in intensive care units, and see fewer specialists.

“Health care organizations serving these low-cost regions aren't withholding needed care,” said co-author Elliott Fisher, M.D., M.P.H., senior associate at the VA Outcomes Group and professor of medicine and community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School. “On the contrary, they are more efficient. They achieve equal and often better outcomes with fewer resources. These organizations offer a benchmark of performance toward which other systems should strive.”

The Dartmouth Atlas Project began in 1993 as a study of health care markets in the United States, measuring variations in health care resources and utilization by geographic areas. The Atlas Project uses large claims databases from the Medicare program and other sources to define where people seek care, identify what kind of care they receive, and determine whether increasing investments in health care resources and their use result in better health outcomes for Americans.

The study was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and a funding consortium including the Wellpoint Foundation, Aetna Foundation, United Health Foundation, and California HealthCare Foundation.

“The Care of Patients With Severe Chronic Illness: An Online Report on the Medicare Program” is posted at<www.dartmouthatlas.org/atlases/2006_Chronic_Care_Atlas.pdf>.▪