A large proportion of people in jails and prisons are in need of acute psychiatric treatment and should be receiving mental health services in the community, according to information presented at APA's annual meeting in Toronto in May.

According to Henry Weinstein, M.D., chair of APA's Corresponding Committee on Jails and Prisons, people with mental illness fell under the auspices of the criminal justice system as state psychiatric hospitals emptied in the 1970s and 1980s and began to fill prisons and jails.

“In addition to being inhumane, it is also very costly to incarcerate people with serious mental illness,” said Weinstein, a clinical professor of psychiatry at New york University and director of the Program in Psychiatry and the law at New york University Medical Center and Bellevue Hospital.

Though deinstitutionalization was originally driven by state budget concerns, incarcerating people with mental illness is costly due to a number of factors. For instance, “these inmates are usually incarcerated for longer periods of time” than are people without mental illness, Weinstein said.

APA committee members have studied the costs of incarcerating people with serious mental illness and have urged legislators to shift adequate funds into corrections to treat them, he said.

“It's in the interest of state legislatures and corrections for these patients to receive treatment in the community rather than behind bars,” he said.

Weinstein and his co-presenters emphasized the importance of mental health courts as one way to divert offenders from incarceration to treatment.

“The resources of the mental health system need to be greatly expanded, with priority given to treating those who are in danger of becoming mentally ill offenders,” said H. Richard Lamb, M.D., one of the workshop's presenters.

Lamb, a professor of psychiatry and director of the Division of Psychiatry, Law, and Public Policy at the University of Southern California, conducted a study of the characteristics of 104 randomly sampled men confined to the Los Angeles County Jail.

The inmates had been identified by jail personnel as having mental illness and housed on a 1,500-bed unit designed for offenders with mental illness.

Based on his findings, Lamb determined that 80 percent of the sample had a serious mental illness, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder.

Lamb and his colleagues determined that 73 percent of the sample was more appropriate for community mental health treatment, while 27 percent were appropriately placed in the criminal justice system because of “lengthy criminal histories of drug possessions and sales and serious property and weapons charges.”

Offenders with mental illness can present unique problems for treatment in or out of the criminal justice system, Lamb noted, due to behavioral problems and treatment noncompliance.

Over 90 percent of the sample had a history of being noncompliant with psychotropic medications, 94 percent had prior arrests, and 79 percent had been arrested for violent crimes.

Tom Hamilton, Ph.D., the past president of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)-Texas and NAMI liaison to APA's Corresponding Committee on Jails and Prisons, was involved in research on Texas inmates, which showed that incarcerating people with mental illness was far more expensive than treating them.

Hamilton highlighted findings from a government study of 100 inmates entering state prisons and county jails in Texas, which found that 1 in 4 inmates had serious mental illness based on matching jail and mental health records.

Those with mental illness had twice the number of jail episodes and three times the number of jail days per episode as the average offender, Hamilton pointed out.

In addition, inmates with mental illness were charged with more infractions per offense than the average nonmentally ill offender.

Hamilton noted that a 2004 cost analysis of inmates in Harris County, Texas, showed that by diverting offenders with mental illness to the community for treatment instead of incarcerating them, there is a potential 40 percent savings per consumer.

Under a program run by the Mental Health and Mental Retardation Authority of Harris County called New Start, offenders with mental illness are mandated to receive outpatient treatment once released from jail.

In 2004, the recidivism rate for offenders who received treatment through the program was 5 percent, according to Hamilton.

“The most unsafe thing you can do is to place [people] with mental illness in prison and not treat them, and then release them to the community without linking them to treatment,” he said.

Prerelease mental health services for inmates are crucial to ensure their success in the community, said Erik Roskes, M.D., director of forensic treatment at Springfield Hospital Center in Sykesville, Md., and a member of APA's Task Force on Forensic Outpatient Services.

“It's important that we realize that transition in this context is extremely difficult for many inmates and especially those with mental illness,” Roskes said. However, postrelease treatment planning can also pose unique challenges, Roskes noted.

For instance, since jail inmates are usually not detained for a lengthy period and may have little notice before their release, it can be difficult to arrange community mental health services for them.

Although prison sentences are longer, and prison staff may have more time to make arrangements for postrelease mental health services, prisons are often located several hours from inmates' homes, which can present problems regarding treatment planning and access to services.

Treatment planning may include psychoeducation regarding medications, addiction, and mental illness, as well as relapse prevention, life-skills education, assertiveness training, and vocational preparation and job placement, Roskes said.

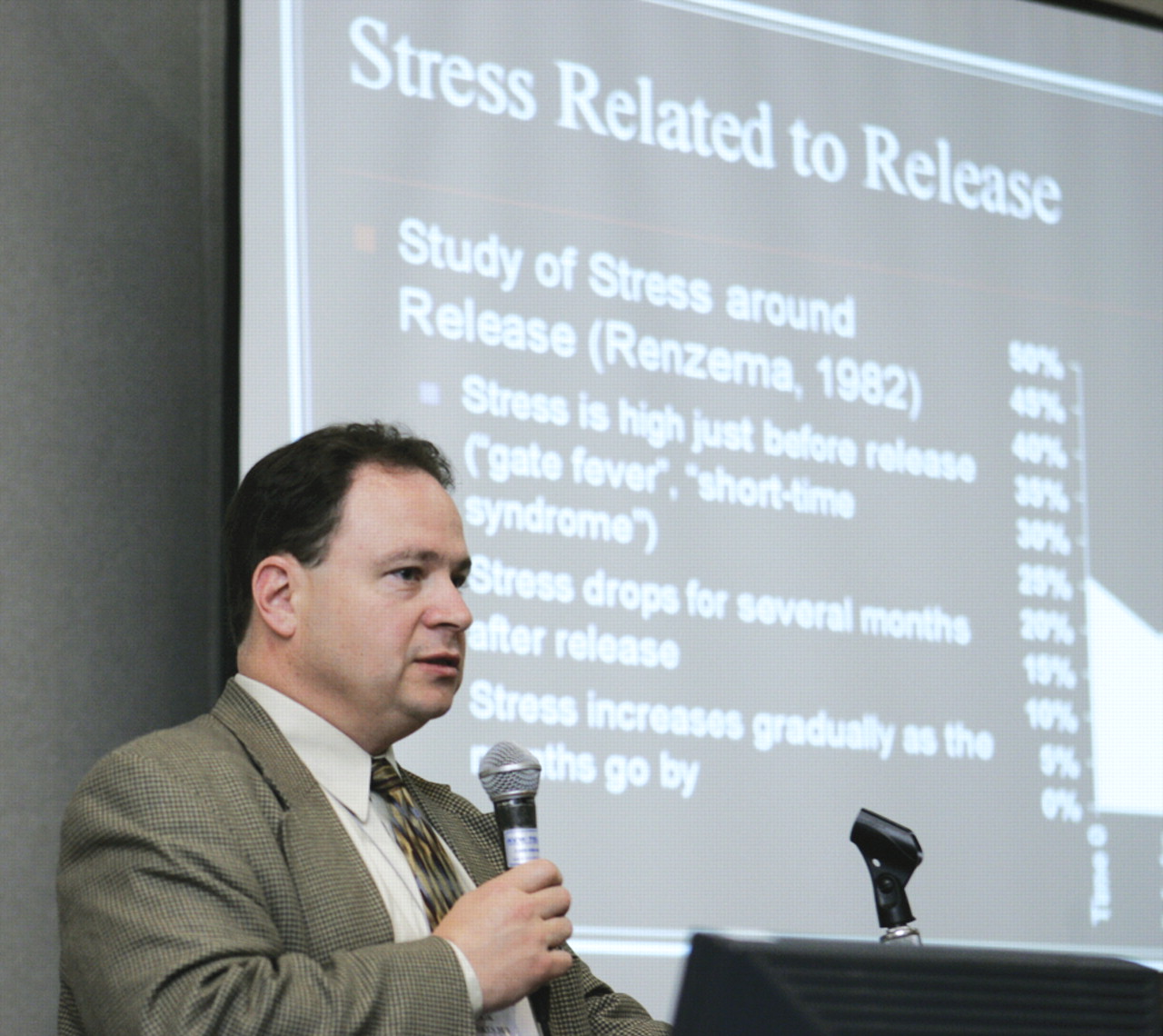

In addition, the days and weeks preceding release can provoke anxiety about being accepted back in the community, he noted. Parole officers and clinicians should be aware that although stress levels may level off after release, they may increase again after “a few months, once they realize it's not so easy being on the outside.”

It is vital that forensic psychiatrists “honestly believe that [offenders with mental illness] can and do recover and change their lives, and we can help them do that,” Roskes emphasized.

Cassandra Newkirk, M.D., noted that it is also important for corrections staff and case managers in particular to note that after spending 30 days in jail or prison, Medicare and Medicaid benefits stop. This can be especially problematic for people who bounce in and out of jail for short periods of time.

Newkirk is director of mental health services for Geocare Inc., a Boca Raton, Fla., company that provides mental health services to people in jails and prisons, and a member of APA's Committee on Jails and Prisons.

“We must advocate for court diversion so that people with serious mental illness never get into the correctional system to begin with,” she stated. ▪