Mood and anxiety disorders have positive associations with obesity in the U.S. population, according to the results of a survey of 9,125 people. Unlike earlier surveys, the study found no difference between men and women in the association of obesity with psychiatric disorders, said Gregory Simon, M.D., M.P.H., and colleagues, writing in the July Archives of General Psychiatry.

Social and cultural factors may play a significant role in connecting obesity with depression, said Simon, of Group Health Cooperative in Seattle, in an interview. “However, we can't say from the data what the direction of causation is.”

The researchers used data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) to examine connections between obesity and mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in adults and whether these were also associated with sociodemographic factors. Interviewers used DSM-IV criteria and assessed participants using the World Mental Health version of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview. The NCS-R survey was conducted over one year beginning in February 2002 and was the U.S. element of a worldwide study coordinated by the World Health organization.

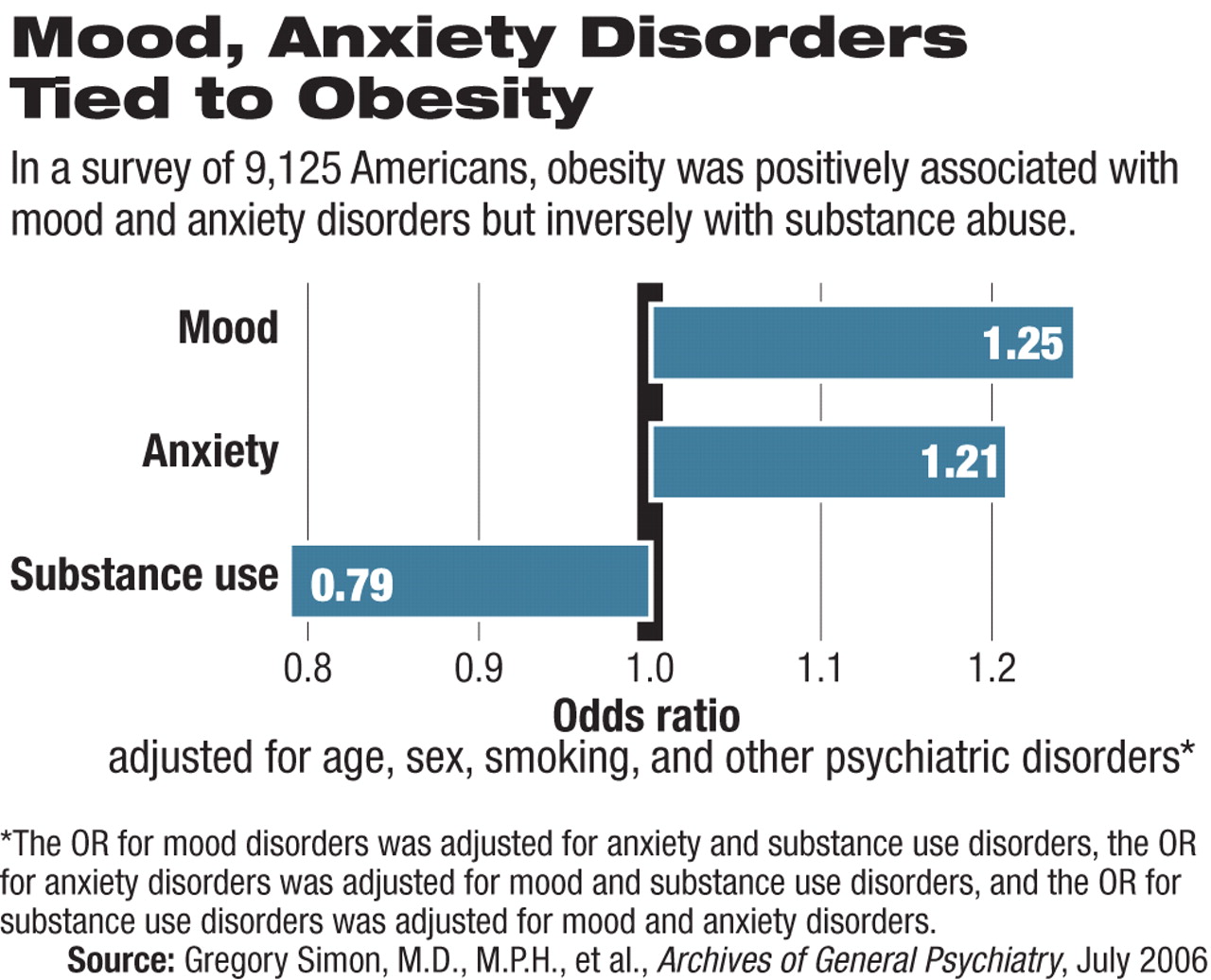

The study concluded that obesity—defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more—was associated with about a 25 percent increase in the lifetime odds of mood and anxiety disorders and a 25 decrease in the odds of substance use disorders. These may sound like modest effects, wrote Simon and colleagues, but are important for public health reasons because of the high levels of obesity in the U.S.

The study measured only association between the two conditions and could not determine whether obesity caused mood and anxiety disorders or whether mood and anxiety disorders induced obesity.

“Many mechanisms could explain the relationship, and possibly more than one is involved,” said Simon. “Some people eat more when they're depressed and some eat less, for example.”

The stigma attached to being overweight might also lead to depression, as well, he said. “In social groupings where obesity is more stigmatized, it might be equally true that people who can't lose weight become depressed, or that depressed people can't lose weight.”

In analyses of various sociodemographic subgroups, the association of obesity with psychiatric disorders was strongest among respondents who were younger than 30 years old, had a college education, or were of non-Hispanic white ethnicity. Simon suggested that social and cultural factors may therefore be important in understanding the connection. Similar studies in China and Poland, for instance, found that increased obesity was associated with less depression.

“I would imagine—although this study doesn't provide specific evidence for it— that if obesity and depression vary with educational and cultural settings, then a social environment that stigmatized obesity would produce more depression and anxiety among overweight members of that group,” said Simon.

“We've seen that behavioral weight-loss interventions reduce weight and also lower depressive symptomatology,” said Eric Stice, Ph.D., a senior scientist at the Oregon Research Institute in Eugene. “But there's not much evidence that treating psychiatric problems leads to weight loss.

“But there's probably a reciprocal relationship. The stress and rejection caused by obesity lead to mood and anxiety problems, while those problems lead to an increased risk of overeating.”

Stigma is no small concern for the overweight, said Stice, who studies risk factors that predict onset of eating disorders, obesity, and depression.“ I'm amazed at what coaches, parents, and other children say about overweight kids,” he said.

The results of the NCS-R study highlight the importance of sociocultural factors linking obesity and psychiatric disorders, said Simon. To explore that link, he and his colleagues are now doing a series of smaller surveys to get more information on the interaction of depression, obesity, diet, and physical activity.